It has, as the kids say, been a minute. I didn’t realise it’s been months since the last newsletter until Substack sent me a gentle reminder, pointing out I haven’t sent out anything in a while. I should have known I was tempting fate when I described The Honey Month as a good book for those in a reading slump, because to simply write “reading slump” is to manifest it. And so it happened. Since April, my reading has slowed down to a drip in slow motion. There’s no reason for it. Nothing dramatic has happened in my life (barring this), but I just didn’t feel like reading anything. So much so that I picked up and abandoned my favourite Discworld books (re-reading Terry Pratchett usually works like a charm. As do paperback romances.)

You’d think the way forward would be to cosset myself with a slim book or picking up something that’s undemanding. Me, I walked over to my neighbourhood bookstore and picked up a book that’s 622 pages long — all because the cover design and endpaper are stunning. (No, it’s not Tomb of Sand. I haven’t read Tomb of Sand. Yet.) It sounds counterintuitive, but I’m coming round to thinking that the best way to tackle a readers’ block is to throw a tome at it. Maybe the simple act of returning to the book again and again helps make reading feel like a habit? Plus there’s the triumph that comes with shutting the book and realising that you are, despite everything, inching across its width. Even if you’ve read just a few pages, it feels like a tangible achievement. On the Kindle, the indicator showing the percentage read, changes. With a physical book, you can literally feel the progress you’ve made because the thickness starts shifting from the unread side to the read side. It’s immensely satisfying. Maybe the next time, the-phenomenon-that-shall-not-be named happens, I’ll crack open War and Peace (haven’t read it). In case you want to try this tactic, Wikipedia helpfully has a page listing the longest novels in the world.

Since we are now officially in the second half of the year and I blipped out for a bit, I thought I’d share a half-yearly round-up in this newsletter. I know I’ve written about most of these in previous editions, but be kind and let me rewind. Here are my six favourite reads from the past six months, stacked in no particular order.

The Honey Month

Amal El-Mohtar’s book is a slim volume of short stories and poems, each one inspired by a particular kind of honey. Every chapter begins with her tasting notes and is then followed by writing that reflects something of the honey. The stories are all about magic and nature, filled with faerie folk, ogres, hunters, rivers that talk in murmurs, and the wonder that the fantastical (and raw honey) inspire. It’s also beautifully-written. Take this entry for example:

“harbour in Penryn

the moon is a sugar-stone

melting on my tongue.”

Now, for ever more, I will think of mishri and moonlight together. This is a treasure of a book.

Lords of the Deccan: Southern India from the Chalukyas to the Cholas

I ‘discovered’ Anirudh Kanisetti because of his extremely-popular history podcast, Echoes of India, in which he talks about a period of Indian history that is usually not discussed as much. One of the reasons his podcast was fun was that Kanisetti approached history not from the perspective of a historian, but that of a geek. Academia tends to categorise and organise facts in a way that separates things like politics, culture, geography etc. Kanisetti wove these strands together and reminded his audience that history is gory, dramatic, fun and interdisciplinary. Lords of the Deccan is written from a similar perspective and provides an overview of the events that shaped the politics and society of southern India in the medieval era. Kanisetti covers about four centuries — it probably helped that scholarship about this era is relatively limited — and highlights the achievements of major dynasties without whitewashing the rulers and their policies. He also points out the gaps and blind spots we’ve inherited since what is placed on historical record is decided by the privileged and/or people in positions of power. If recounted by an enthusiastic and dedicated researcher, any period of history comes across as fascinating and Lords of the Deccan is powered by Kanisetti’s enthusiasm and curiosity. He does an excellent job of cramming the events of a few centuries into 400-odd pages. Pacy is not a word usually associated with history books, but Lords of the Deccan is just that. It moves at a trot and I pretty much devoured it over a weekend.

The Mere Wife

It’s been months since I read Maria Dahvana Headley’s modern retelling of Beowulf and the first page of the novel still gives me goose bumps. Headley begins the book with a page titled “selected translations” in which she reveals a detail about the way Beowulf has been translated in the 20th century:

While aglaeca (the masculine noun) was translated as “hero” to describe Beowulf, the feminine version of the same word (aglaec-wif) was translated as “hag” when describing the mother of the monster/ dragon that Beowulf kills. Also, in case anyone was wondering, there is apparently no consensus on how aglaeca or aglaec is pronounced, so knock yourselves out and say it as you will.

Coming back to The Mere Wife: Headley sets her story in contemporary America. Her Grendel is a boy named Gren, who seems monstrous to society because he’s different. His mother is a war veteran and rape survivor. When she gives birth to a dark-skinned baby with golden eyes, she retreats into a forest and raises her son in hiding, keeping him away from mainstream society’s hateful gaze. It works for a few years, but the forest stands at the edge of a gated community and Gren ends up making friends with a little boy who lives in the posh suburban township.

The Mere Wife is about a contest between two mothers, rather than a face-off between a hero and a monster. The story is interesting, but it’s Headley’s language that makes this novel special. She writes about violence, sadness, rage and despair with muscular, electric elegance. When language is described as lyrical, we tend to assume it’s also delicate and soft; like the textual equivalent of a camera using soft focus. Headley’s writing is the opposite. Its lyricism is emphatic and vivid. The descriptive phrases come at you like a force of nature. I underlined chunks of text on practically every page while reading this novel. So, so good.

Red Carpet: Hollywood, China, and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy

I’ve been going around recommending this book to pretty much anyone and everyone who has crossed paths with me since March. Erich Schwartzel does such a good job of explaining how and why Hollywood has become China’s submissive in the past few decades, and what this means for storytelling in English commercial cinema. If you’re interested in film or enjoy cultural criticism, you have to read this book.

A Memory Called Empire

I gushed about Arkady Martine’s space opera in the last newsletter, so I won’t go on about it too much, but it’s such a delight to read a story that is able to balance its high concepts with all the tension and drama you expect from a standard political thriller. I’m feeling all the more appreciative of Martine’s storytelling skills right now because I watched Thor: Love and Thunder yesterday and that film is packed with insights and thought-provoking ideas, but when it comes to the basic mechanics of a story — stuff like relationships, characterisation, suspense, climactic action sequences — it fails. Martine, on the other hand, got it right. Her novel is layered with reflections upon identity, culture, imperialism, patriotism, memory, technology and surveillance, but it’s also the story of an ambassador who finds herself in the middle of a political coup. Plus, the queer love story that’s tucked into the twists and turns of A Memory Called Empire is so well-written.

The Absolute Book

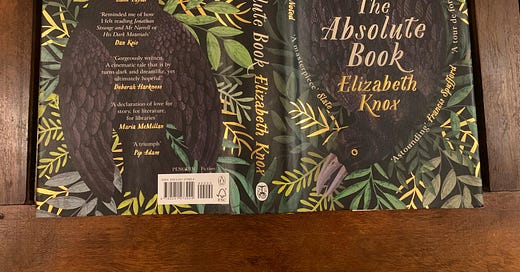

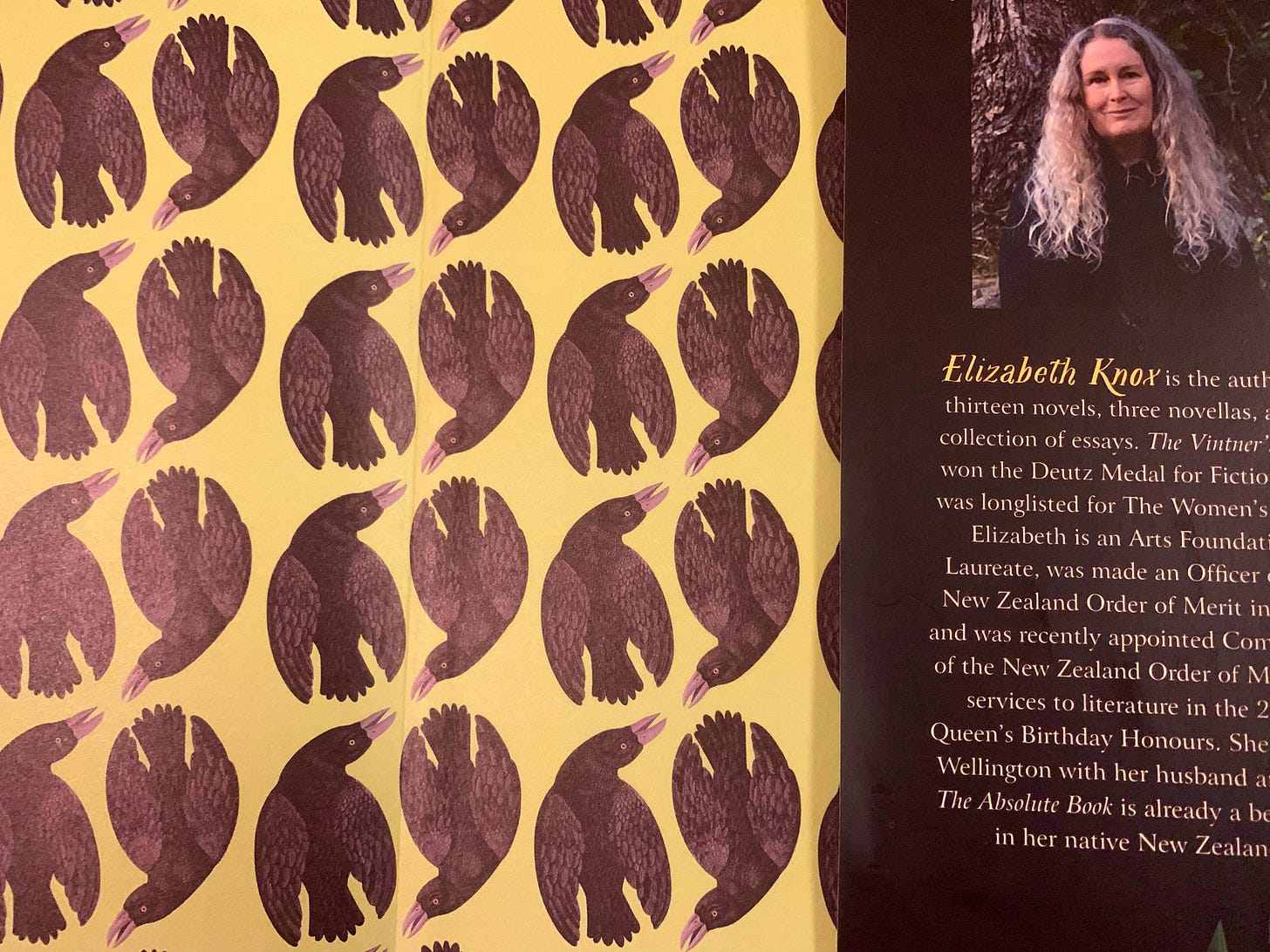

This is the tome that I picked up for its cover design and endpaper. Can you blame me?

The camera doesn’t do the cover justice, by the way. Every time I’d close the book, the light would catch the scattered leaves that are gold-embossed, and it was like a glint of living magic in my hands. The book has also been printed on fantastic paper that is just the right balance of grainy and smooth. I remember hesitating for a fraction of a second when I saw it’s priced at Rs 799, but this book is worth every penny of that amount. It’s been produced with such care and attention to quality that it spoils you (I was flipping through another book recently and the pages felt coarse and finesse-less compared to the paper quality of The Absolute Book. It’s not a big deal, but we tend to forget that reading a physical book is a tactile experience). Brava, Penguin Random House UK.

The Absolute Book is my introduction to New Zealand author Elizabeth Knox so I had no idea what to expect when I picked it up. The plot synopsis sounded a bit like a crime thriller that has as its starting point the death of a teenaged girl and the shadow this incident casts over the girl’s sister in particular. Crime and violence are very much a part of The Absolute Book, which puts its heroine, Taryn Cornick, through some terrifying situations. But The Absolute Book is also a fantasy, complete with otherworldly creatures and a heroic quest.

Taryn was a teenager when her sister Beatrice was killed in a hit and run. The perpetrator was sentenced to six years in jail, which seemed absurd to Taryn, especially since she’s convinced her sister’s death was not an accident but a deliberate murder. Soon after Beatrice’s killer is released from prison, he’s found dead and police detective Jacob Berger is convinced Taryn is involved in some way. At the same time, Taryn starts getting silent phone calls from a mysterious stalker and having ‘episodes’ that suggest she’s hurtling towards a nervous breakdown.

As if all this wasn’t complicated enough, a stranger named Shift introduces himself to Taryn. Shift tells Taryn that there are different realms that exist parallel to the world we live in, and beings from these realms can slip in and out using “gates” that are operated using metallic gloves. One of these parallel realities is Purgatory. Another is the fairy realm that is home to Shift. There’s a delicate equilibrium between these various worlds, built on ancient terms and agreements; and that peace is now under threat. At the centre of the unrest is a book known as the Firestarter, so called because it’s survived a string of mysterious library fires.

Somehow, Knox has written a novel that is as much a crime thriller as it is a fantasy adventure. It’s elaborate, messy and magnificent. There are odes to nature even while she crafts an alternative, impossible and unreal world. Details are layered, one upon the other, so that as the story progresses, you start seeing there’s more to the people, incidents and objects than you realised at first. For instance, there’s a scene in which we see an actor do a screen test for a fantasy film, entirely unaware that the creatures he’s seeing are not actors in costume. It’s simultaneously funny and frightening. Knox makes sure the reader is aware of both the absurdity that the self-important actor radiates as well as the danger posed by the creatures around him. You know those lenticular images, which look like one thing but then you tilt the image a bit, and a whole new picture becomes visible? The Absolute Box reads like that.

Knox draws upon a wealth of references — from Hugin and Munin of Norse mythology to Gaelic folklore about fairies and a dazzling array of literary allusions — as well as personal stories. Beatrice’s death is similar to how the author’s brother in-law lost his life. Like Taryn, Knox also lost her mother some time ago (she had ALS and Knox was her carer). Literature festivals get a look-in, as do libraries.

The Absolute Book takes the desire to escape this world, with its senseless cruelties, and uses it as a prism through which to examine questions about sacrifice, privilege and personhood. What are happiness and beauty worth if you don’t know ugliness? What are you without your memories? How many individuals will you sacrifice for the greater good? How important is it to be seen by those you love? Knox’s novel is an exploration of grief and pain, as well as a celebration of life; it’s about worldbuilding and the price you’d pay to preserve the world you’ve built. It’s not for everyone, but then no ambitious book is. Towards the end of the novel, The Absolute Book takes a turn that feels forced, but as Knox put it in an interview, she was “writing my way into happiness”. If you’re willing to give The Absolute Book your time and attention (and grant it a little suspension of disbelief), it will repay you with magic.

So that’s my pick from the last six months. I hope you’ve all been well and 2022 is being kinder to you than 2021 was. Take care, thank you for reading, and Dear Reader will be back soon.