The Honey Month + the Teixcalaan series + Vladimir

In March — which seems like a year ago — I managed to sneak in the newsletter just before the last day of the month ended. Not so in April, even though it turned out to be a really good month as far as reading went. Which is why you’re getting this newsletter now, in the middle of May. Oops… .

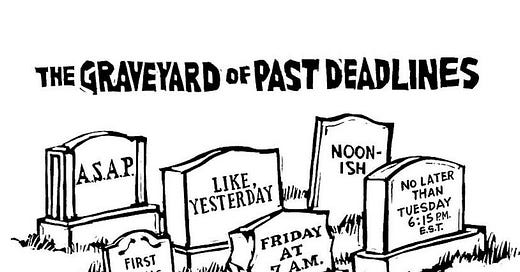

I would solemnly swear to be more punctual in the future, but that would probably be as effective as my perennial resolution to keep things short and crisp in here.

(cartoon by Drew Dernavich, nicked from the New Yorker’s Insta feed.)

Reader, what follows is a newsletter, not a chip. It will be neither short nor crispy. Partly because I have FIVE books I want to tell you about and also because I’ll add to the word count with paragraphs like this one in order to (vaguely) justify the GIFs that will follow. Such is life.

On to the books…

Vladimir by Julia May Jonas

When a book titled Vladimir opens with an older woman confiding to the reader that she’s kidnapped a younger man because he’s (ahem) sparked joy in her, you’re going to think of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. By the end of it though, Julia May Jonas’s novel reminded me more of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. Only unlike the cantankerous duo at the heart of Albee’s play, Jonas’s middle-aged, married couple is exhausted and a manifestation of that meme that shows a burning room in which a dog calmly declares “This is fine.”

Jonas’s protagonist is a whip-smart professor of literature in her late 50s who works in a well-respected liberal arts college. Her husband is a sleazebag and the chair of the department. He’s currently being investigated following accusations of sexual harassment, sparked by #MeToo conversations. While figuring out how to navigate a way through the scandal and the whispered rumours of her being her husband’s enabler, our protagonist meets the department’s new hire. Vladimir is an assistant professor. He is also husband to a gifted and troubled young writer whose work leaves the older woman feeling envious.

Admittedly, Vladimir flounders towards the end and the way Jonas ultimately ties up her story feels like an anti-climax (though entirely credible). Despite this, there’s a lot to love in this novel. An older woman as a narrator; how #MeToo has impacted the way we see the power dynamics in a relationship; writers’ block and intellectual camaraderie; ageing and the connection between eroticism and youthfulness — Jonas has packed so much into Vladimir. And Jonas manages to be light, elegant and funny while exploring all this.

An excellent non-fiction companion piece to this novel would be The Right To Sex by Amia Srinivasan, particularly the essay in which she considers #MeToo in academia.

Oh, and if you’re interested in Lolita and Nabokov, this excellent podcast examines the novel and the way it’s lingered in popular culture.

The Invisible Library by Thorvald Steen (translated by James Anderson)

This novel is both intriguing and frustrating. Steen imagines the last days of Alexander the Great, but from the perspective of his mistress, a woman named Phyllis. Historically speaking, there’s no definitive explanation for how Alexander died and Steen blends existing research with his imagination to recreate the past.

So long as Steen stays in 323 BCE, The Invisible Library is gripping. Unfortunately, there are a few annoying interludes in which the author deliberately derails the story by dragging in the present. Also, I feel like I needed to know a lot more about Alexander and his time to properly understand and appreciate this novel.

When The Invisible Library opens, Alexander is lying paralysed and in agonising pain. The suspicion is that he’s been poisoned. An imprisoned Phyllis has been ordered to write down everything she knows about what may have led to Alexander being in this state.

Over the next 200-odd pages, Phyllis tells us the story of her life, beginning with how it was turned upside down when her husband joined Alexander’s army. After she was widowed, Phyllis found work as a cook with the army and eventually became Alexander’s mistress. She’s a charismatic storyteller and a determined survivor. Meanwhile, Alexander is surrounded by disgruntled soldiers and scheming subordinates. Phyllis’s memories reveal the hero as a man of many faces — sometimes petulant, sometimes brilliant; often cruel, always suspicious. Many, including Phyllis, find themselves both hating Alexander and loving him.

Steen writes some fantastic descriptions of life in the camps. You see how Phyllis is changed by war and how Alexander is changed by his circumstances. At the heart of the novel are the questions of how Alexander is remembered and what goes into the myth of Alexander the Great.

Outside The Invisible Library, Phyllis as a character shows up in the tale of Phyllis and Aristotle. There are many versions of the story, but all of them agree that Aristotle lusted after Phyllis (she’s sometimes identified as Alexander’s mistress and sometimes as his father’s mistress). So enamoured was Aristotle of Phyllis that he had her meet him secretly and let Phyllis ‘ride’ him as a dominatrix. He had no idea that Phyllis had set up the scene and made sure Alexander witnessed his beloved teacher being her sub. The sight of Aristotle on all fours has been faithfully remembered by generations of Western artists (their revenge for being forced to study Aristotle perhaps?).

The whole episode is supposed to show how even the smartest man — i.e. Aristotle — can be reduced to a hormonal puddle by a woman. Steen retells this story in The Invisible Library in a way that shows how women — particularly non-aristocratic women — had to live by their wits in ancient societies.

At the end of The Invisible Library, Steen has a section titled “Twenty-One Notes”, which he begins with, “I have allowed myself to update Phyllis’ text to our own time and render it in my own voice.” I would love to read the original because it would be fascinating to know what has been added/ modified/ removed by this “update”. Of couse I looked up Phyllis and her text, but Aunty Google was most unhelpful. This is very unsettling. I’d forgotten how it feels to be effectively Googlewhacked.

A Memory Called Empire and A Desolation Called Peace by Arkady Martine

The moment I read the first page of A Memory Called Empire — “This book is dedicated to anyone who has ever fallen in love with a culture that was devouring their own” — I was hooked.

Cultural politics is not the kind of thing I expect from science fiction (which I’ve read very little of because most of the time, it just feels like a jigsaw puzzle made up of weird names, weirder gadgets, pseudo-scientific theories and men being manly. Unless you’re reading the entirely amazing Ursula Le Guin. Or Margaret Atwood. Or Douglas Adams.)

Then, I learnt A Memory Called Empire was Martine’s first book, which she’d written while reading for her PhD in Byzantine history. She has since changed lanes and works in city planning. She’s also writing/ written another novel which is expected next year. She also has the most beautiful red hair. You may insert heart-eyes here.

A Memory Called Empire is set in a time and place that feels simultaneously strange and familiar. There’s no Earth in this corner of space. Instead, there’s the empire of Teixcalaan, with its capital city, known as the Jewel of the World; and vassal planets. Mahit is from a tiny imperial outpost called Lsel and she’s spent most of her life studying the literature, language and culture of Teixcalaan. She loves it deeply even while being acutely aware that as far as Teixcalaan is concerned, foreigner subjects like Mahit can only ever be barbarians.

(Take a moment to consider how close this hits an Indian who chose to study English literature and has had to repeatedly give credentials to prove her proficiency in the English language — particularly in America and the UK — despite her academic qualifications and the minor detail of India’s history of being a British colony.)

When Mahit is appointed Lsel’s ambassador to Teixcalaan and must go to the Jewel of the World, it feels like a dream. She has no idea that she’s been sabotaged by one of her superiors in Lsel and that she’s arriving in Teixcalaan at a critical and turbulent time. The current emperor is old and there are people plotting to overthrow him. There are whispers of revolution on the streets. Oh, and Mahit’s predecessor was murdered — possibly by one of the people who wants to overthrow the emperor.

A Memory Called Empire is partly a story about court intrigue and politics. There are dead bodies, tense interrogations, shifty allies and a whole lot of suspense. It’s also an exploration of what it means to belong to a culture as well as the relationship between an individual and their cultural heritage. And to top off this literary cake, there’s also a dollop of queer romance. I loved every moment of this novel.

Martine’s worldbuilding skills are phenomenal and she doesn’t so much describe the Jewel of the World as much as immerse the reader in it. The architecture in the capital city and the way it’s laid out will make you think of world cities that you love (from the Byzantine Constantinople to modern-day New York City, it’s all there in the Jewel of the World). Teixcalaan has many intriguing conventions, like using numbers, flora and tools in their names. (I had to look up what an adze is. It’s kind of amazing how knowing the meaning of a name impacts the way you receive the character associated with that name.) Most children in this world are clones and very few women choose to be pregnant, which makes them something of a curiosity in society. Both Teixcalaan and Lsel are unconcerned about gender and sexuality, which is refreshing and would be utopic if so much else about these societies didn’t induce heartburn. Among the more unnerving details of Teixcalaan is the way its security forces use technology to ‘connect’ individual minds. Those policing the capital are hooked to a single network, which means what one officer sees, hears and even feels is transmitted on the network to every other colleague. This collective intelligence takes on the proportions of a nightmare in the sequel, when Teixcalaan faces a military attack for the first time in an age, and each fighter feels the fear and pain of those dying alongside them.

While A Memory Called Empire is about the postcolonial individual’s love-hate relationship with a dominant culture, Martine explores the idea of collectives and hive-minds in the second book in the Teixcalaan duology. In A Desolation Called Peace, Teixcalaan finds itself on the brink of a war when a strange, new species attacks a planet on the far edges of the empire. Back on Lsel, Mahit realises she has no allies or friends at home. She escapes the politicking on Lsel by taking on an assignment to be a diplomat for the Empire and establish first contact with the mysterious enemy that’s decimating planets and steadily inching closer to Teixcalaan.

A Desolation Called Peace is very good and the concepts it explores are thought-provoking, but it didn’t feel as powerful as A Memory Called Empire. This was partly because Martine sounded like a tour guide in the early sections of the book, offering explanations of Teixcalaan’s practices and conventions. Maybe if I’d had to wait three years for the sequel, I would have appreciated this, but since I’d pounced on A Desolation Called Peace minutes after finishing the first book, it felt unnecessary. Also, while the world of A Memory Called Empire felt dazzlingly novel, A Desolation Called Peace is mostly set in a spaceship that’s in a war-like situation, which feels quite familiar thanks to all the Star Trek shows we’ve seen over the years.

The Honey Month by Amal El-Mohtar

What would you do if you were given a box of honey samples? If you’re Amal El-Mohtar, then you’ll jot down the cutest tasting notes, and then write something full of magic and fantasy inspired by that honey. There are 28 chapters in The Honey Month. Most are short stories, but there are also a few poems in there. Some are chilling, many will make your heart ache a little, and all of them glisten with lyrical beauty. The only things connecting the stories in each chapter are the honey samples and the storyteller. El-Mohtar is a word-witch, spinning absolutely gorgeous yarns. Among my favourites are the stories inspired by the thistle, raspberry creamed (!) and manuka honeys.

I can’t recommend this book enough. If you’re in a reading slump, The Honey Month with its short, unconnected chapters is a great way to nudge yourself back into the habit of reading. For those who want the adrenaline rush of a binge read, this volume can be finished in a day because El-Mohtar’s language flows with ease and grace. You’ll probably want to go back to it though, to savour the imagery and the fantastic craft that holds the book together (it’s like a hive with each chapter working like an individual cell). Whatever it is that the past few months/ weeks/ years have thrown at you, if you have any love for fiction, then The Honey Month will feel like a comfort. The best of fantasy writing offers an escape from the familiar and leaves you with a sense of hope when it returns you to your real world. The Honey Month does just that. It might also make you look up some obscenely-expensive honey online.

And that’s the best of my April, for your reading pleasure. I hope this year is being kinder to you than the last one was. If it isn’t, hang in there and may you never fall short of distractions.

Take care and thank you for reading. Dear Reader will be back soon.