Last week, a colleague asked me whether a certain feature is available on Substack “since you use it”. I’m pretty sure I must have winced in response. These newsletters are far too infrequent for me to claim any kind of expertise with Substack and it’s still a mystery to me that I have any subscribers at all, but this seems like a good time as any to thank you for being here and for the 52% of you who are actually opening the newsletter when it appears in your inbox. No shame to the rest of you. Thanks for adding to the numbers. Truly.

You’ll be happy to know that I’m not writing to you out of some swelling sense of guilt for having gone so long without sending a newsletter out (guilt, for me, is not a good motivation to write. More on that some other time), but because three of the last four books I read have been so good that I’ve wanted to press them into the paws of anyone and everyone I can. (The fourth — Unbroken by Indrani Mukerjea, who is accused of having killed her daughter — is exactly the opposite. I was hoping to call it a ‘guilty pleasure’ just for the joy of cheap puns, but the writing is too terrible to qualify for any kind of pleasure. Also, for the record, Mukerjea maintains she’s innocent and her daughter is alive. The point at which she wanted to put on record the size of her ex-husband’s penis is when I abandoned the book. Not all knowledge is power.)

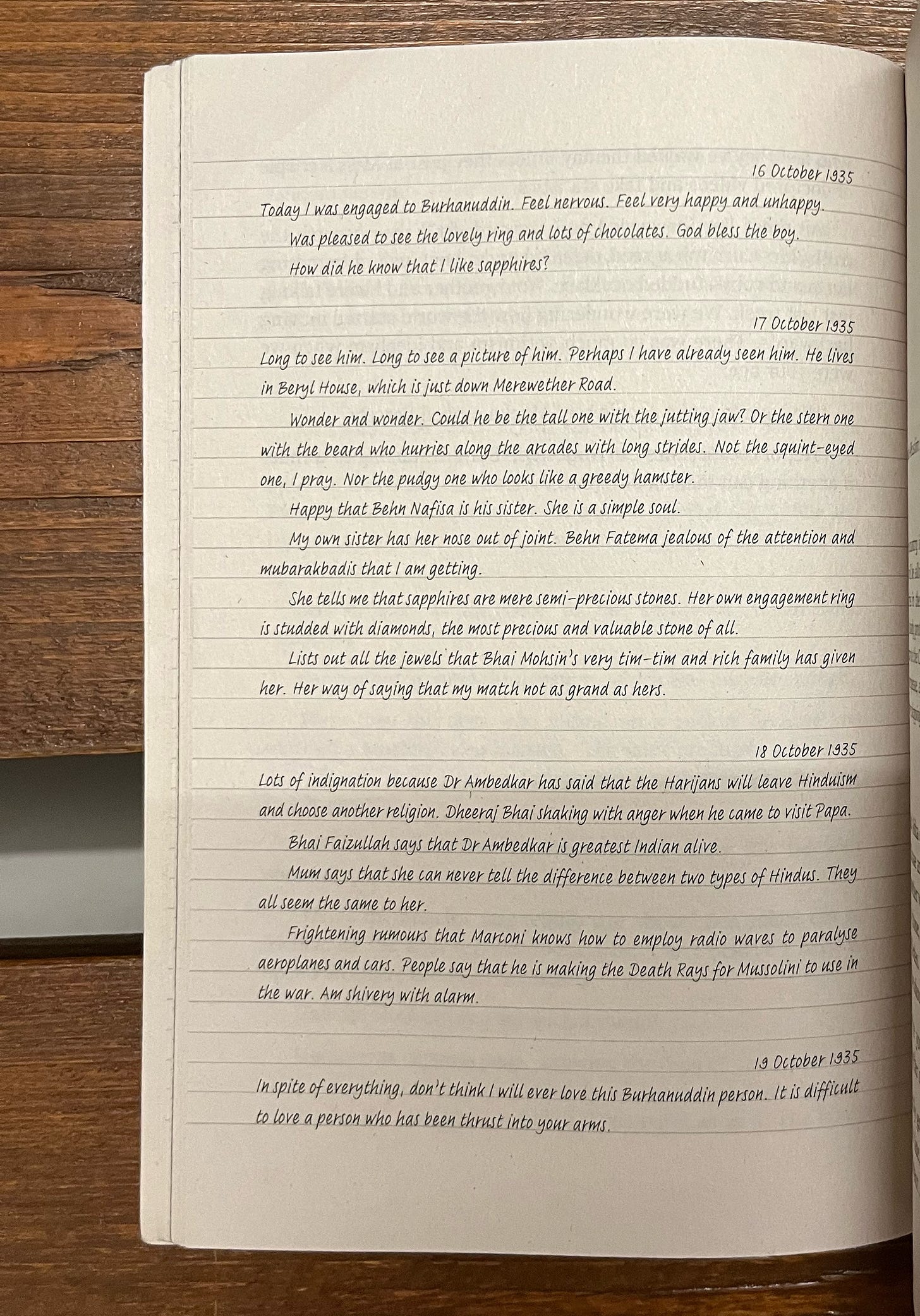

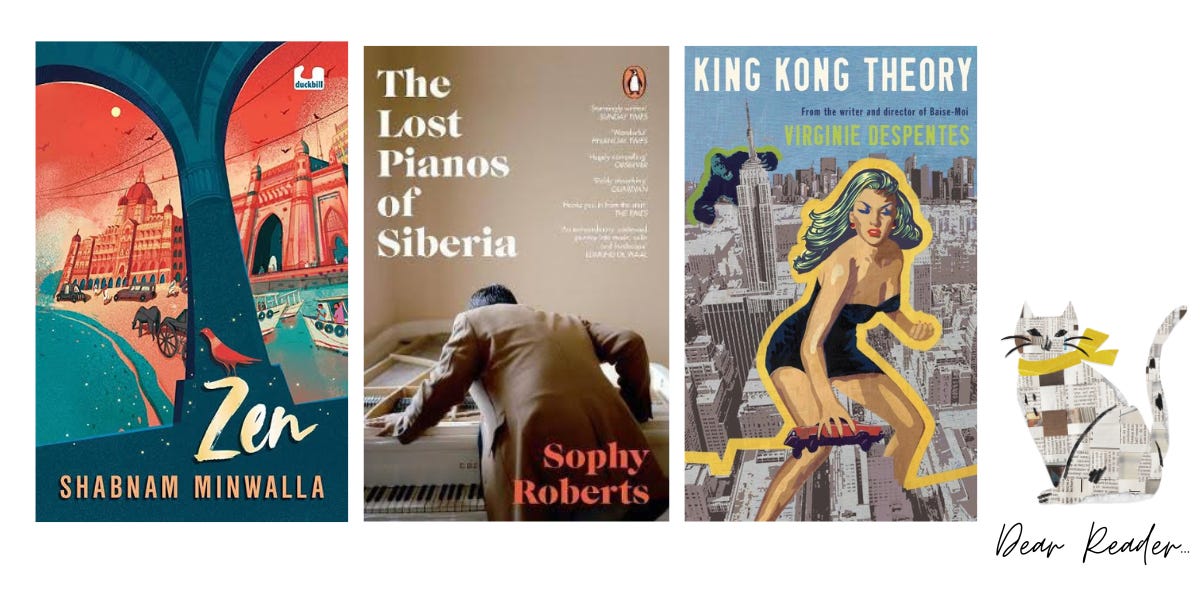

Coming back to the good books — let’s start with Zen by Shabnam Minwalla. Set in Bombay and Mumbai, Zen is the story of young women coming into their own when the world around them is burning. The titular Zen is a teenager in the present who is forced to think about her identity and politics when the protests surrounding the Citizenship Amendment Act erupt and she finds she’s got a crush on a young man who feels like the wrong one. Interspersed with Zen’s story are fragments from the diary of Zen’s family matriarch, Zainab, who had her brush with romance and politics in 1935, a time when the independence movement in India was gathering strength. Scattered between these two young women’s stories are fragments from a spectral presence who haunts Zen and Zainab (and gives me goosebumps even now).

I picked up Zen very casually, mostly because Bijal, whose wonderful book Savi and the Memory Keeper now has a US edition (YAY!), told me to read it. I expected Zen would take me a week or so to finish it since it’s a fat book (600+ pages). Two days, that’s how long it took me to race through this novel. It would have taken me less time if I hadn’t given myself a stern talking-to about reading in the office instead of doing work, but *plugs in halo*, Reader, I was good.

Zen is a love letter to an idea of India that is under serious threat today. It’s also an insider’s postcard of south Mumbai at its most charming. Minwalla weaves the history and landscape of that part of the city into her story with masterful ease. This is one of those novels that couldn’t take place anywhere else. The personality of both Mumbai and those who belong to the city are intrinsic to Zen. It’s a privileged Mumbai, peopled with ‘people like us’, and there’s nothing wrong with that because Minwalla writes in a way that feels keenly-observed rather than insular. She’s also crafted some fantastic women and girls, like Zen, her friends, Zainab and Zainab’s sister. Perfectly-paced, steadily written and filled with love, Zen is the kind of book you sink into, the kind of story that makes you care for strangers. I can’t recommend this book enough — and this is despite the godawful choice of font for the Zainab sections.

This font, dear reader, is the font of Satan. It is there to test you and only because Zainab’s irreverent honesty is so utterly charming, do you pass the test and stick with the book. I suspect Zen is a little more enjoyable if you’re familiar with Mumbai, but if you don’t know anything about the city, this book would be a delightful introduction. When it’s written well, young adult fiction has the gift of feeling accessible. Its authors are able to take dense ideas and unpack them in a way that doesn’t feel laborious. Minwalla does exactly that in Zen. She looks at subjects like Muslim identity in contemporary India and underscores the importance of being political, of standing up for progressive values. The hope that she holds out through Zen is one that’s particularly precious now, at a time when we hear of a new, horrific incident of Islamophobia in India daily (and all of them go unpunished. Even virality and widespread visibility isn’t enough to make the government feel any shame or compunction anymore). Stories like Zen are the songs of our dark times and I, for one, can only feel gratitude for bards like Minwalla.

Another book I picked up without thinking is The Lost Pianos of Siberia — it’s always a little unsettling to realise that my best decisions are the ones taken with the least amount of deliberation on my part. On the plus side, we can rejoice that the universe is looking out for me (at least so far as books are concerned)? — and it turned out to be absolutely riveting. Journalist and travel writer Sophy Roberts spent two years looking for pianos in Siberia because listening to Mongolian pianist Odgerel Sampilnorov, whose family had been forced to leave Siberia in the 1930s, Roberts wondered “how an historic piano would sound different in the steppe.” And so she set off to find historic pianos in Siberia, with the intention of finding one that could be brought to Odgerel in Mongolia. Which sounds as elegantly bonkers as an idea can be. White people, I tell you. You could argue that being privileged and inheriting a culture of feeling entitled helps, and I’m sure it does. Still, to not just think of lost pianos in Siberia, but to actually spend two years travelling through that region looking for said pianos, and finally piecing together an exquisitely beautiful travelogue and potted history of Russia — through pianos! — is just genius.

Photograph by Michael Turek, who accompanied Roberts. You can see more of his work here.

The Lost Pianos of Siberia is an absurdly beautiful book, mostly because of Roberts’ writing style (there are some photos and they’re good, but nothing compared to the language). Roberts is one of those rare writers whose lyrical prose is so evocative that I didn’t find myself turning to Google’s image search for photos, not even of physical places she was describing. She’s cherrypicked the perfect lines from the conversations she’s had during her travels (one of my favourites is by a man who moved to the Altai Mountains after seeing an exhibition of paintings by Nicholas Roerich: “The world is very remote. We are at the centre.”). I felt like could see through her words, and it was enough. For example, this is about a historic performance of Shostakovich’s Leningrad symphony in 1942, performed during the siege of Leningrad:

“In late June, Shostakovich’s score was airlifted into the besieged city and the improvised orchestra — playing in layers of old clothes, described by one participant as ‘dressed like cabbages’ — began to prepare as best they could.

The drummer perished on his way to work, wind players fainted for lack of food, while musicians were pulled out mid-rehearsal to go fight fires. When a date was finally fixed for the Leningrad premiere, Soviet artillery targeted German guns within range of the Philharmonic Hall, where the performance would take place, to ensure the Nazi bombers wouldn’t be able to overwhelm the music. …

In the falling afternoon light of 9 August 1942, the city’s hungry populace fell silent for one of the most dramatic moments in an incomprehensible war. ‘[W]e were stunned by the number of people, that there could be so many people starving for food but also starving for music,’ said the trombonist: ‘Some had come in suits, some from the front. Most were thin and dystrophic.’ When it was over, not only Leningraders but also German soldiers listened to the half-hour standing ovation given by a people on its knees.”

Siberia’s history is, of course, scarred with terrible suffering and hardship, and Roberts doesn’t use her wordsmithery to prettify any of the ugliness. The reminders come frequently and eloquently:

“Confronting memory and repression, I knew that however hard I wanted my piano hunt to celebrate all that is magnificent about Siberia, much of what I was looking for was tied up with a terrifying past. I needed to heed the warning I was given by a brave Russian journalist early on: you have to know why you’re ignoring things you don’t want to hear, what should be remembered, and why people fall silent and try to forget.”

The emphases are mine because they cut deep into my mind as I think of India today. Pick up The Lost Pianos of Siberia if you’ve been feeling a lack of wonder in your life. Yes, it’s packed with solid research and reportage, but it’s unlikely that you need to know about pianos in Russian history from 1762 till the present. There’s nothing utilitarian or pragmatic about this book, and that’s what makes it magical.

And finally, a book that I started reading because of my friend and podcast partner Supriya Nair: King Kong Theory by Virginie Despentes. Yes, you can find it as an e-book, but take my word for it, you want the physical book. Because the Fitzcarraldo Editions are just so darned satisfying to hold in your hands and feel under your fingertips. Their books are tactile perfection — pages that are just the right thickness, smooth with just the whisper of friction — and I’m quite sure there’s a part of me that kept reading simply because I wanted to feel that paper under my fingers. It’s books like these that make reading a truly sensual experience.

Incidentally, the Fitzcarraldo Editions’ cover is a stately, minimalist white with the title in a neat, blue font, but I loved the pop chaos of the cover above, which really matches the punk energy of Despentes’s writing.

King Kong Theory is a memoir as well as a manifesto. Despentes writes about significant episodes from her life and also presents a savage, insightful critique of patriarchal, capitalist society. Written in language that is blunt, punchy, unsentimental and precise, King Kong Theory is a magnificent read. Despentes’s prose has the energy and rage of a rap as she hammers away at capitalism and the prejudices that fester in our society because of it. She writes about difficult and often painful subjects, including her own experiences as a rape survivor and as a sex worker. Yet there’s not one moment that feels self-indulgent or performative. This is writing that’s as honest as it is sharp. Despentes also made me think a lot about the super-violent, revenge fantasy genre of films that I generally find distasteful:

“When men create female characters, it’s rarely an attempt to understand what they are feeling or experiencing as women. It’s usually just a way of putting a male sensibility in a female body … we see how men, if they were women, would react to rape. A merciless, violent bloodbath. The message is clear: how come you don’t defend yourselves more aggressively? And it is pretty astonishing that we don’t react that way. An implacable, age-old political ideology teaches women not to defend themselves. As usual, it’s a double bind: on the one hand, we’re told this is the worst thing that can happen, on the other, that we shouldn’t defend ourselves or exact revenge. We should suffer, and be unable to do anything else. The sword of Damocles, between our legs.”

Yup, I did indeed clench my thighs when reading that last line.

It’s not that I necessarily agree with everything Despentes says in this book, but I enjoyed not just reading her arguments, but also figuring out where and why I disagreed with her. I started reading it when I was very unwell and no, I didn’t recover because of the book, but it made my brain, which was even sludgier than normal, raise a tiny viva-la-revolution fist as it creaked and groaned its way into critical thinking. King Kong Theory is a book that urges the reader to reject the world around them and think their way into creating a better one. Can’t ask for more than that. Here’s another taste of Despentes:

“Obviously, being a woman is difficult. Fears, constraints, required to be silent, expected to fall in with a system that has long since had its day — a panoply of idiotic, pointless limitations. We are still the aliens, the ones expected to do the dirty work, and churn out the raw materials while keeping a low profile. But compared to being a man, it’s a walk in the park… Because, in the end, we’re not the ones who are most terrorized, most helpless, most shackled. Ours has always been the gender of endurance, of courage, of resistance. Not that we had a choice.

True courage. Facing up to what is new. Possible. Better. Employment is collapsing? The family is imploding? Good! This automatically challenges notions of masculinity. More good news. We’ve already had enough of this shit.

Let me leave you with a little bit of etymology. The word “gossip” has its origins in the Middle English word “godsibb”, which in turn is made up of “god” and “sibb” (sibling, relative). In Middle English, a godsibb was a friend or kin, a person considered a relative of god. A woman’s godsibb made up her circle of trust. The transformation of godsibb into gossip (with its connotations of nasty idleness) happens at the same time that witch hunts become prevalent in Europe. This linguistic change is effectively a record of how women’s solidarity was attacked and villainised. As someone who is fortunate enough to have her circle of gossipy godsibbs, I hope you find your own, both in books and life.

Thank you for reading Dear Reader.

Loved reading your newsletter. Thanks for introducing these gems. I am hearing about these books for the first time. Non-fiction rarely appeals to me, but your description of The Lost Pianos of Siberia piqued my interest, one day I will get to it.

Cheers :)

I keep coming across Zen and hadn't wanted to add it to my ever-growing wishlist, but you've convinced me!