Whereabouts + What We Know About Her + Unwell Women + The Lit Pickers S2

On the face of it, the life of a book reviewer seems to be the stuff of dreams for a bibliophile. You get piles of free books, discover new authors and get paid to write about new releases. Yay! However, the reality is a wee bit different. Good books — that is, books you enjoy reading; books that move you and make you see the world differently; books that you want to write about — are unicorns and most of the books that one encounters as a reviewer are …

… not unicorns.

However, every now and then, there will be a book that reminds the reviewer that nestled deep within them, under the stone mattress of disappointments that is life, is a Writer. Out of their love for the book (and a teensy weensy bit of disgruntlement that the universe has not given the reviewer an opportunity to publish their magnum opus), what emerges is a review that is actually a literary gun show packed with all the poetry and lyricism that a reviewer can muster. Sometimes it works and a good review can convince the reader to pick up the book in question. Most of the time, a critic attempting to be poetic leaves a reader feeling either confused or impatient.

Which is why I’m going to keep it simple — Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri and What We Know About Her by Krupa Ge are my two favourite fiction reads of 2021 (so far).

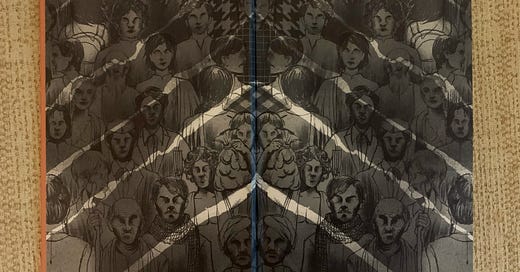

To be honest, I wasn’t expecting to love either of these books. Lahiri’s previous novels didn’t wow me and the synopsis of Whereabouts sounded unbearably pretentious: “The woman at the center wavers between stasis and movement, between the need to belong and the refusal to form lasting ties.” It seemed only right to not form any lasting ties with this book, even though Penguin India had kindly sent me a review copy. I’d read a lot about Krupa Ge’s critically-acclaimed non-fiction book, so was quite happy when Context sent me her debut novel What We Know About Her. I opened the book and was faced with this spread, which convinced me that her book was a horror story about people whose eyes have been scooped out.

But then I read the synopsis on the book’s flap and there was no malevolent creature, natural or supernatural, with an unquenchable lust for eyeballs. Instead it sounded like yet another multigenerational family saga by a desi author. Reader, I confess, I eye-rolled. Then I did something far worse — I forgot about both books.

Fortunately, whether or not this is true for soulmates, it is definitely true that a book will find its reader precisely when the time is right, despite all odds.

Whereabouts initially feels like a collection of interconnected short stories masquerading as chapters of a novel. There isn’t really a plot. Instead, there are vignettes depicting awkward friendships, complicated mothers, difficult fathers and familiar strangers. With each story, we get a little more of the mosaic Lahiri is putting together. Eventually, what comes through is the solitary life of a 40-something university teacher, in an unnamed Italian city. Each chapter reads like an exquisitely-written journal entry. She describes routine things, like a plaque that she sees when out for her daily walk. She also tells us about out-of-the-ordinary events, like the small tantrum she throws at a dinner party. Lahiri doesn’t spoon-feed her readers. Instead, she trusts us to forage for the significant details and make the necessary connections, which in turn makes the experience of reading Whereabouts feel intimately personal and satisfying.

Also satisfying are the short, almost self-contained chapters that give you a sense of how the nameless narrator has compartmentalised different aspects of her life. This structure is also perfect for all of us whose pandemic brains can’t focus on one thing for more than a few minutes at a time. Most importantly, it makes excellent use of Lahiri’s masterful short story-writing skills. Much of the charm of Whereabouts lies in its chapters possessing the elegance and precision of a meticulously-crafted miniature. Each one begins at a certain point, builds up to a quiet climax as the narrator arrives at another point, and ends with a sentence that almost always feels like a deep cut. As the novel progresses, we realise the narrator is actually on the brink of a big change and what we’re reading is the account of a woman taking stock of her past as she prepares for a new chapter in her life.

It might be a bit of a spoiler, but this business of coming to terms with the past in order to move forward is also at the heart of What We Know About Her. There are other similarities between Lahiri and Ge’s novels. For instance, both books have a lonely, woman narrator who is also an academic and who has a difficult relationship with her mother. I could probably write a whole essay on mothers and the concept of mothering in these two novels because both re-sculpt the traditional image of motherhood in their respective cultures …

… but I’ll spare you.

Coming back to Ge’s debut novel, What We Know About Her is about a woman who is trying to figure out how much of the past she wants to carry into the future through the choices she makes. It will probably leave you wishing you could write a book about your own grandaunt/ grandmother/ grandfather/ grand something. As far as I know, all the characters in the novel are fictional, but they feel real because of how well Ge writes them and because our cultural legacy does include some amazing, charismatic women like Ge’s fictional Carnatic singing legend, Lalitha.

The narrator of What We Know About Her is Lalitha’s grandniece, Yamuna, who is fighting with her mother to hold on to a piece of ancestral property. She’s also grating on the nerves of other family members because she’s trying to uncover a family secret that they’d rather keep hidden. For much of the novel, we see Yamuna trying to establish her claim upon what she considers her inheritance — the worn interiors of her home in Chengalpattu (which is, according to Wikipedia, 56 kilometres from Chennai) and Lalitha’s story as told in the letters that Yamuna’s grandfather doesn’t want her to read. There’s a scandal in Lalitha’s life that has been judiciously covered up and Yamuna’s curiosity is seen as a threat to how Lalitha would be remembered.

What We Know About Her meanders through Varanasi and Chennai, with Yamuna as the readers’ guide through these cities where time seems to stand still. The voice that Ge has crafted for Yamuna is pitch perfect and within a few paragraphs, you can practically hear Yamuna as you read the novel. Ge also deserves an extra round of applause for her descriptions of various places in Varanasi and Chennai, which feel familiar even if you don’t know the cities. As she pesters her grandfather for stories and digs around to learn more about her grandaunt Lalitha, Yamuna realises this family history makes for a complicated legacy; one that is characterised by beauty and strength, but also cruelty and cowardice. In the middle of all this, Yamuna’s grandfather decides to play Cupid and introduces her to his friend’s grandson, Karthik. This is particularly surprising because Karthik is not of the same caste as Yamuna. Yet there’s Yamuna’s Thaatha, humming marriage songs as he notes the sizzle of attraction between her and Karthik.

Yamuna and Karthik’s love story runs parallel to the untold tale of Lalitha’s marriage, which Yamuna learns of in tantalising fragments. The fictional Lalitha is charismatic enough and needs no real-life parallel, but while reading about her, I was often reminded of the legendary singer, MS Subbulakshmi. There’s something deeply ironic about women artistes finding themselves in a musical tradition that is so patriarchal and misogynist, and enriching it artistically despite all the challenges they face at home and in the professional arena.

It isn’t as though What We Know About Her is perfect. The climax is a damp squib and the conclusion is rushed. The present-day discussions about caste, religious identity and privilege often feel shoehorned and there’s an unnecessary red herring that floats around aimlessly, raising questions about Lalitha’s last years. The secret that the family has been carrying around for decades doesn’t pack as much of a punch as an earlier revelation about Lalitha’s husband. Karthik remains a bit of a blur as a character and feels like the Jiminy Cricket to Yamuna’s Pinocchio. His relationship with Yamuna moves in awkward jumps and their dates seem to be an excuse for Ge to describe Chennai life, which she does beautifully but the romance teeters between being either a prop or a distraction. This is a shame because thematically, Yamuna’s love story is important to What We Know About Her.

Yet these flaws don’t really take away from the pleasure of reading Ge’s novel and immersing yourself in Lalitha’s story and Yamuna’s world. When I reached the last page, I didn’t want to leave Yamuna. I wanted to know what she’d do next and I wanted to shadow her as she moves on — which sounds a little creepy, but really is a compliment.

The other book that I read and enjoyed recently is Elinor Cleghorn’s fantastic overview of how women have been failed by medicine and contributed to its success, titled Unwell Women: Misdiagnosis and Myth in a Man-Made World. I’m not sure if picking this book up while doubling over with painful menstrual cramps was necessarily my smartest idea since a section of the book describes the work of professor and researcher Clelia Duel Mosher.

“Mosher asked her to loosen her clothing, lie with her knees flexed, and apply gentle pressure to her abdomen with one hand. She was to breathe in deeply and see how high she could raise her hand by lifting her abdominal muscles, and then observe her hand lowering as she exhaled and her muscles contracted. Mosher asked her to practice this exercise ten times, morning and night…”

I would happily give both my ovaries and part of my liver if this exercise would rid me of menstrual cramps as it did Mosher’s patient, but sadly I’m not one of the lucky ones. I remain the equivalent of the Disney princess, waiting impatiently for her Prince, i.e. Menopause, to come (bring on the hot flashes. I’ve survived loadshedding in tropical summers). But I digress.

Unwell Women is a great read for anyone interested in history and science. Cleghorn shows how women, who were traditional healers, were sidelined by the founding fathers of ‘scientific’ medicine. She goes on to show how women were forced into a passive position as patients before social movements in the modern era made it possible for women to regain some agency, both as patients and practitioners within the Western medical system. Cleghorn has dug up some incredible case histories and statistics, which she uses to inspire both shock and awe as she shows us how women patients have been treated from ancient times to the contemporary present. What emerges is a chilling dichotomy. On one hand, doctors dismiss the medical symptoms that women report but on the other hand, more women patients have been subjected to radical surgeries like lobotomies and hysterectomies than men. From being denied anaesthesia during delivery to being operated upon as a test subject and being given drugs that were considered too dangerous to administer to chickens and men, the injustice and pain that women subjects have suffered at the whims of the male medical establishment is horrifying. Cleghorn includes stories of subjects who were practically erased, like the Black women who were experimented upon by American doctors in the slavery era. She highlights the work of women (and men) who fought for the dignity of women patients and shows how social movements for gender and racial equality impacted the history of medicine. It’s an attempt to spotlight those who have been erased, and I wish more people would do this.

Cleghorn looks at how unquantifiable experiences like pain as well as illnesses like endometriosis, fibromyalgia and lupus have been misdiagnosed and mishandled over the ages, often leaving women patients to suffer terrible consequences. As someone with lupus, she’s seen first-hand how the medical establishment fails women patients because the reference point is always masculine. The power dynamic between a doctor and a patient becomes all the more uneven when the patient is a woman (imagine how much worse it is for those who are trans). The inequality that women encounter in society informs how they’re treated by the medical establishment. Contrary to their reputation of objective impartiality, science and medicine are mired in social prejudices. Medicine has a long history of pathologising behaviour and character traits that are considered feminine but undesirable. Unsurprisingly, the treatments are almost always intended to make a woman more docile and passive.

Cleghorn does her best to give us some relief from the relentless cruelties and disappointments by talking about researchers and doctors who have worked towards improving things. However, it is painfully obvious that even now, the medical establishment is overwhelmingly biased towards men and continues to dismiss women. Women’s medical issues are not considered important enough to research systematically, which is why things like menopause and fibroids remain (by and large) a mystery.

Women who are reading this, please keep a record of your ailments and medical history. Write about your periods, your pain and the changes that you feel in your body. Men who are reading this, please encourage the women you know to do the above. It doesn’t matter if no one pays attention to it today. Keep a record and who knows? Perhaps in the future, when someone like Cleghorn goes looking for accounts and personal histories to understand what hasn’t been documented, your words will find them.

I think it’s time I stopped rambling, but before I go, I have a little announcement. Season two of The Lit Pickers will be here on August 6th. For those of you who are new to this newsletter, The Lit Pickers is a podcast in which the generally fabulous Supriya Nair and I talk about books and reading. Feel free to binge on the first season (available on pretty much all podcast platforms), which includes episodes on Jane Austen, Ramayana, JRR Tolkien, literary festivals and Harry Potter. The idea of a second season of The Lit Pickers came up during boozy brunches with our winsome producers, Mae and Shaun, and despite buzzkills like lockdown, the second wave of Covid infections and whatever passes for governance in India today, we have been able to put together some fun conversations.

And that’s all I have for you this time. Take care, mask up, be kind to yourself and say a prayer for everyone as we navigate these strange, surreal times.

Thank you for reading. Dear Reader will be back soon.