VS Naipaul: Aug 17, 1932 to Aug 12, 2018

I wrote this for a blog that I have on my site and then thought I'd share it with you here, since I haven't got round to finishing any of the books that I started since I sent the last newsletter. Terrible, I know. Fingers crossed August goes better. Meanwhile, here's a little something on Sir Vidia.

Just yesterday, a friend and I met for a long overdue brunch and ended up fretting over Sir Vidia the man and VS Naipaul the author. (It was our version of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie society; just without the eye candy of Michiel Huisman, sadly, but with excellent pasta. So there’s that). Naipaul came up because the conversation had found its way to that familiar fork in the road: can the personality and politics of a creator can be separated from their work? I struggle with that question because of people like Naipaul, I told my friend after we’d compiled a quick list of authors (all male. What a coinkydink…) who occupy a spectrum of dickishness, but are nevertheless extraordinarily gifted when it comes to writing and storytelling.

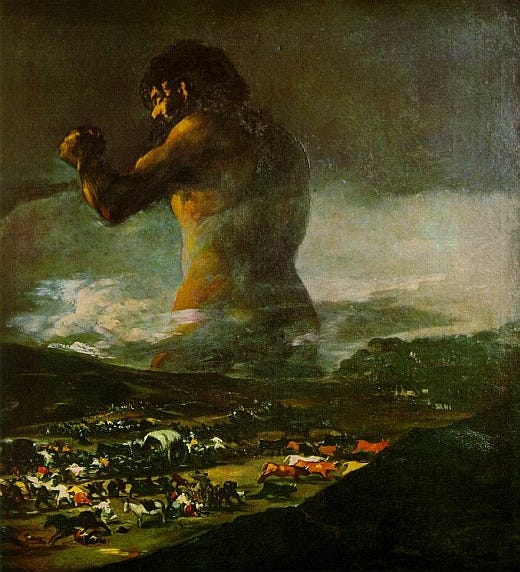

Less than 24 hours later, there are headlines announcing the passing of literary giant VS Naipaul, Sir Vidia. It made me think of the mysterious Colossus attributed to Francisco Goya. Protector or one on rampage? Trapped in the landscape or rising out of it? Causing people to flee, forcing us to stare at him. I wish I’d thought of this curious parallel when I was sitting in the audience, listening to Sir Vidia speak, charmed and disgusted by the man and his words in equal parts.

If you’ve never read any of Naipaul’s writing, pick up A House for Mr. Biswas, An Area of Darkness, India: A Wounded Civilization, The Enigma of Arrival and A Bend in the River. But don’t begin or stop there, because this writer who wrote precise, perfect sentences and offered slicing insight through his narratives was also a man who could make your skin crawl with his brutish conservatism. He was charming and he was offensive. He was brilliant and he was infuriating. His personal flaws are visible in his writing, in the good writing especially. His obnoxious, regressive beliefs were wounds he carried, wounds that oozed the pus of Brahmin pride, misogyny, Islamophobia and racism. And yet somehow, they hardened into unexpectedly powerful literary scar tissue.

Naipaul was born in 1932, in Trinidad, to journalist Seepersad Naipaul who had literary ambitions and overbearing in-laws. Seepersad, born to a man who came to the island as indentured labour, and the turbulent relationship he had with his wife were the inspiration for A House for Mr. Biswas. Naipaul’s childhood was difficult. He would later reveal he was molested as a boy; his parents fought constantly; there was little money — his refuge was literature. He consumed European literature and devoted himself to writing when he grew older (especially after his father passed away).

His intellect and affinity for literature had wrapped him in a sense of superiority that suffered cruel blows when Naipaul came to England in the 1950s, as a scholarship student to Oxford University. It didn’t matter how perfect his English was, he didn’t belong with the whiteness he’d vaguely idolised but neither did he want to belong to the communities with which he was effectively lumped in a violent, racially-divided culture. Naipaul’s early years in England were tormented, lonely and angry. As a student, vowed to beat the Englishmen in his class — rub their noses in the fact that this coloured, colonial migrant had claimed ‘their’ language with his mastery. As an author, he challenged them with his style, his subjects and the genre boundaries that he blurred.

To a reader (particularly one who of postcolonial lineage), Naipaul’s writing is powerful and troubling because he exposes the coloniser’s lies and brutality with ferocious elegance. But his rage is also directed at the (de)colonised, whom he unforgettably described as “half-made”. At a time when we demand political correctness, the unrepentant chauvinism and racism in Naipaul’s writing is shocking. Think twice before picking up that quotable quote in which he savages the imperialist coloniser. What exactly are you saying you agree with, when you quote Naipaul, and why? Because he’s also gone on to justify and even make a virtue of Islamophobia and racism.

From the migrant outsider who was isolated and segregated, Naipaul would go on to become as central to British English literature as is possible. He would be knighted in 1990 and awarded the Nobel prize for literature in 2001. As journeys from periphery to centre go, this was epic. Fortunately, it’s been written down both in Naipaul’s own words – he often mined his own experiences for his fiction and as an author of non-fiction, he is the narrator who lords over his narrative — and those of others. There are at least two books on Naipaul that deserve to be read and re-read: Patrick French’s The World is What it is and Paul Theroux’s Sir Vidia's Shadow: A Friendship Across Five Continents. The first is an authorised biography and one of the most gripping and candid portraits of the man that Naipaul was. The second resulted in one of English’s literature more juicy feuds.

What the biographies and so many of Naipaul’s interviews reveal is the tormented, abhorrent man who hated himself and lashed out at so many others. In addition to trotting out opinions like, “Africans need to be kicked. That’s the only thing they understand” to emotionally abusing his wife with his words and infidelities, and physically abusing his mistress, Naipaul list of flaws is monstrously long. A lot of it seems to be transmuted self-hate, but it’s still toxic and the only bulwark against Naipaul’s vileness is his skill as a storyteller. But even as you’re awed by the lyrical precision of his sentences, remember that his odious beliefs are nested in his writing.

And what is one to make of the fact that Naipaul has admitted to being a monster? Some give him credit for his candour and honesty when questioned about ex-wife Patricia Hale and former mistress Margaret Gooding? (Hale was the one he cheated on and abused emotionally, going so far as to admit at one point that the hurt over the years, even after they’d parted, may well have hastened her death. Naipaul beat Gooding viciously and would later tell French, “I stayed with Margaret until she became middle-aged”.) Others — I’m part of this tribe — are horrified by not just his actions, but the fact that he feels empowered and secure enough in his male privilege to make such admissions.

Usually, RIP trips off the tongue when someone passes away, but I don’t want Sir Vidia to rest in peace. I don’t think his brilliance affords him that privilege. One doesn’t mourn the passing of a monster. But one does remember them and the fact that they were characterised by both their magnificent rage and their ugliness.

The Washington Post’s obit for VS Naipaul is a wonderful read. It also has this interview with Naipaul in which he says a whole bunch of odious things and then says something that you want on a t-shirt: “If a writer doesn’t generate hostility, he is dead.”

The charm of Sir Vidia is beautifully remembered and represented by Teju Cole in this essay from The New Yorker.

The Guardian’s review of Patrick French’s The World is What it offers a summarised version of some horrific aspects of Naipaul’s personality.

Naipaul’s “On Being a Writer” is a thought-provoking read. “The point that worried me was one of vocabulary, of the differing meanings or associations of words. Garden, house, plantation, gardener, estate: these words mean one thing in England and mean something quite different to the man from Trinidad, an agricultural colony, a colony settled for the purpose of plantation agriculture. How, then, could I write honestly or fairly if the very words I used, with private meanings for me, were yet for the reader outside shot through with the associations of the older literature?”