The February List

I know it's March, but February was a weird and terrible month, which despite being weird and terrible, was also full of some great reading. Bear with me for a moment while I geek out on you by going off on a tangent about the etymology of “weird”. Its root is Germanic. In Old High German, “wurt” meant “fate” and from there, around 1400, the word “wyrd” had emerged. It was used to describe those who could control fate or destiny. Approximately four hundred years later, the meaning had shifted and the word was used to describe uncanny things (like the three weird sisters in Macbeth). By the 19th century, “weird” meant unnatural, which is a weird turn for a word that began its life as a term meant for those who control the natural.

February was weird because I stood at the edge of worlds that collapsed for those I care about deeply, and could do nothing more than empathise with them while standing witness to their grief. And I read. I spent 10 days away from home and work, and ended up reading more than 15 books in that time. Many of these were books for children and young adults – thanks to my friend Bijal, the patron saint of kiddie fiction – which meant they were slim and quick to read, but hey, a book’s a book. And frequently, there's so much packed into the simplicity of a picture book that you finish reading it in minutes, but return to it again and again for days.

The grown-up books I was reading were mostly about fantasy and magic while a lot of the kiddie books were about nurturing a sense of wonder. It struck me at one point that no matter which age group you belong to, the good picture books will leave you starstruck even though they’re meant to be for kids. There's as much in each stroke as there is in a sentence that's crafted with care, and both seek to enchant you. With picture books, though, the kind of reactions you have feel more immediate. This is not just because few of us can draw and paint with the kind of sophistication that we see in picture books, but because in addition to all the technical skills the storytellers possess, these books show the imagination at its most iridescent, unfurling itself like a peacock’s tail.

Speaking of peacock’s tails, this podcast has nothing to do with books and everything to do with how boy birds attract girl birds for sexual purposes, but I’m linking to it anyway because it was so much fun.

Coming back to books, it’s not as though books for grown-ups don’t evoke wonder, but somehow, the picture books I read last month felt stronger. You didn’t have to sink your toes into words and sentences, you didn’t have to make an effort. You just turn the page, and something magical is before you. To be able to do that to a person in the present is amazing because we’re surrounded by so much stimuli (much of which is visual) – books, films, video games, social media, photographs, podcasts etc etc. How, in the middle of all this, do you create/ write something that makes someone feel wonder?

And now for the 15 books from February list. These do not include the Mills & Boon paperbacks that helped make the world a better place. For all of you who are aghast that I read romance novels and think that this genre is for idiots, one day I will write my thesis on the amazing cultural creation that is the paperback romance novel. This time, though, let’s look at the fantasies that were spun by the authors whose books I read in February.

NK Jemsin’s Broken Earth Trilogy (The Fifth Season, The Obelisk Gate and The Stone Sky): Usually, the point of a fantasy series is to prevent the apocalypse. Jemsin turns this idea on its head and instead tells her reader early on that there’s no escaping the apocalypse. In the Stillness, where the Broken Earth trilogy is set, the only thing that is certain is that the earth will wreak havoc and the worlds built by humans are doomed. Jemsin follows a woman of many names who is looking for her daughter. Quickly, we realise that what is important is surviving in the present. In the course the quest to find the daughter, a group of outsiders become a collective that is determined to enter the future rather than be erased by the present. Layering the fantasy are explorations into issues that are important to us in our present-day, unfantastic societies: ethics, hierarchy, discrimination and the damage done to the environment. I think the first book is still my favourite for how fabulously Jemsin crafts the landscapes of Stillness and the way we’re introduced to the central characters. The first two won the Hugo award for best science fiction or fantasy novel.

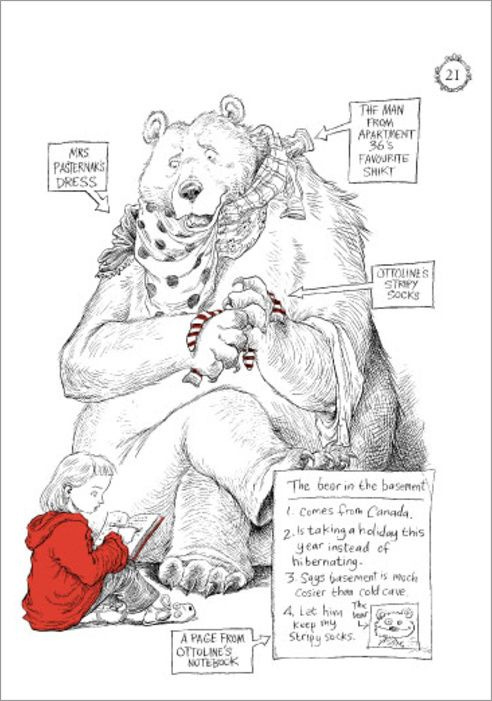

Chris Riddell’s adventures of Ottoline (Ottoline and the Yellow Cat, Ottoline Goes to School, Ottoline and the Purple Fox, Ottoline at Sea): Normally, perhaps the highest praise I can confer upon someone is to say they’re good storytellers, but that phrase just doesn’t seem to be enough for Chris Riddell. This man is a magician – not only because he draws beautifully (he does), but because he really knows how to use illustrations in a way that they don’t just accompany words, but add to the story wordlessly. Ottoline is a little girl who is also a master (mistress?) of disguises and solver of mysteries. She lives in a big apartment with her friend and guardian, Mr. Munroe who is all hair, some eyes and a native bog dweller from the armpit of Norway. Ottoline’s parents are explorers who are constantly travelling, but they’ve got an army of help to make sure Ottoline has everything she needs. Plus, her mother sends postcards and letters and gifts regularly. Left to her own devices, Ottoline goes around having delightful adventures that are entirely silly and utterly adorable. Plus, you can frame every single page and spend ages staring at Riddell’s incredible linework. I cannot recommend these books enough. Especially if you’re a grown-up who keeps abreast of current affairs, the Ottoline books may be just the wormhole you want to retreat to when it all gets too much.

This is the bear Ottoline meets in the basement. The bear is from Canada and has decided to go on holiday instead of hibernating. I approve of this choice.

Nirmala and Normala by Sowmya Rajendran and Niveditha Subramaniam: Once upon a time, two sisters were separated at birth. One was raised by a famous film director and became the epitome of all things filmi and feminine, and was named Nirmala. The other, Normala, was raised by nuns and went on to do regular things like go to college, ponder whether she can fall for someone who reads Chetan Bhagat, and obsess over why the guy she likes hasn’t called her back. The plot is basically an excuse for Rajendran and Subramaniam have fun with the clichés associated with women, femininity and love. Wicked and irreverent and super fun, especially if you’re familiar with the tropes of popular Indian cinema.

Asmara’s Summer by Andaleeb Wajid: If you like romantic comedies and are looking for a pick-me-up, this is utterly charming. Set in a Bangalore, the novel is about a teenaged girl who’s forced to spend summer with her grandparents while the rest of her family go off to Canada. Asmara is dreading this because unlike her parents, her grandparents live in a grungier part of Bangalore. Fortunately, there’s a rather good-looking neighbour who seems to be on the roof whenever Asmara’s on the terrace. Still, there’s no airconditioning in the house, people want to marry off teenagers, Asmara has to nick wifi from a neighbour to use her iPad and Asmara’s skimpy shorts are giving her grandmother palpitations. Andaleeb writes about these older Bengaluru neighbourhoods with the affection and irritation that is reserved for old favourites and tackles rather thorny issues of class and stereotypes with grace and candour.

Julian is a Mermaid by Jessica Love: This is one of the loveliest picture books you’ll ever read. Every page is a work of art and the relationship between Julian and his grandmother gave me the warm fuzzies. I know it’s meant for kids, but considering how little conversation there is around trans identity, most of us could do with this book on our bookshelves. This is another book whose every page deserves to be framed.

From Julian is a Mermaid

When Paul Met Artie: The Story of Simon & Garfunkel by Gregory Neri: Two pages into this book, I had to start playing my Simon & Garfunkel playlist. Despite having once bumped into someone who was either Art Garfunkel or his lookalike (gotta love New York City), I had no idea how these two had met or the twists and turns they took before Simon and Garfunkel was born. Each chapter has one of the group’s songs as its title, which is why you’ll feel the need to hear the songs, and the brightly-coloured illustrations may just make you feel a little nostalgic.

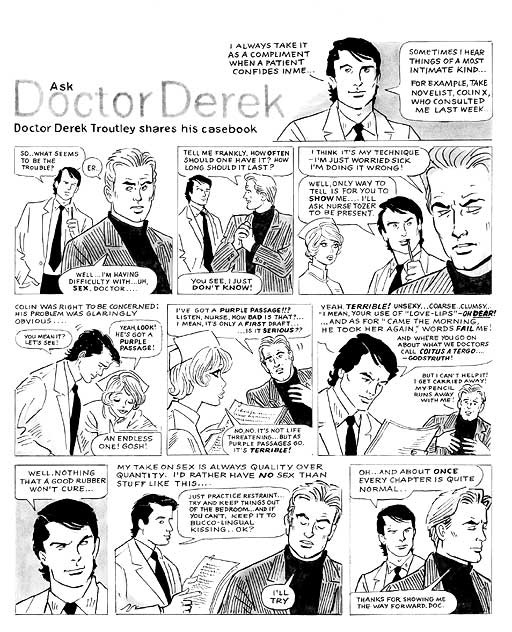

Literary Life Revisited by Posy Simmonds: This is a must-have and must-read for those interested in the world of publishing and literature. Simmons’s cartoons – it seems wrong to call such clever storytelling ‘just’ cartoons, but hey, that’s my bias talking. Cartoons are sophisticated stuff when drawn by sophisticated folk – are revelations. She’s telling you stories from the British publishing, but I think these stories are practically universal. Particularly love the literary clinic cartoon strips, where a doctor prescribes cures for writing problems. So. Much. Fun.

From Literary Life Revisited

Blood, Bullets, and Bones: The Story of Forensic Science by Bridget Heos: While it wasn’t quite as gripping as I’d hoped it would be, Heos’s overview of how science played an increasingly important role in detection and crime solving is a thoroughly engaging read. This is apparently meant to be a young adult book, which is kind of unnerving to me until I think back to the murder mysteries I was devouring at age 15. The crimes that she’s compiled in this book are fabulous.

Blood, Water, Paint by Joy McCullough: If you don’t know Artemisia Gentileschi’s story, then this novel in poetry is going to feel a little bit like word soup. Stick with it and it eventually ends up being rather delicious, but the biography that gives the poetic novel context comes at the end of the book. It’s also not detailed enough. In 1612, Artemisia Gentileschi’s father went to court, accusing an artist named Agostino Tassi of having raped his daughter. She was 18 or 19 at the time of the trial and had been a year or two younger when Tassi had raped her. Over the course of the trial, she would be tortured (her hands would be mangled) to prove she wasn’t lying about being raped. Still, Tassi was eventually found guilty. This was a victory, but one with a dull edge because he had influential patrons thanks to whom the sentence he received was light. The brunt of ill was weathered by Artemisia who was quickly married off and packed off to Florence. Artemisia would later find fame for all the right reasons later when she became the first woman artist to become a member of the Accademia di Arte del Disegno in Florence. She’s best known today for her paintings of strong, rebellious women from Biblical stories. It’s not as though Blood, Water, Paint doesn’t have bits that would move people even if they didn’t know Artemisia’s life story. The point at which she’s tortured, for example, was hard to read and my hands felt stiff with empathetic pain. Unfortunately, as it is, McCullough’s ambitious book just doesn’t do Artemisia’s story justice. McCullough has chosen to write the book using two voices. Artemisia’s dead mother, who tells her stories from the Bible about women who are able to win against powerful men, speaks in prose. Artemisia herself speaks to us through poetry, which is an excellent writerly device because it allows McCullough to write about brutalities like rape and torture evocatively without getting into realistic details. But the world in which Artemisia lives doesn’t come through clearly enough and neither does this remarkable woman’s character. If any of this sounds even remotely interesting to you, I would highly recommend you read Artemisia Gentileschi by Mary Garrard, but for the minor detail that it is stupidly expensive. Aside from Garrard’s insightful writing, the book includes Artemisia’s letters and the transcripts of the rape trial. Artemisia’s words will give you goose bumps.

Jadoowallahs, Jugglers and Jinns: A Magical History of India by John Zubrzycki: In his introduction, Zubrzycki makes it clear that the point of his book is not to reveal how magic tricks are done. Instead, he’s interested in how magic was perceived, the reputation that it gave India in the colonial era and what the tricks that the magicians performed revealed about the world and society around them. This book is a fascinating overview over Indian magic and street magicians. It starts with the Mughal emperor Jahangir and concludes with PC Sorcar in the 1950s. Until reading this book, I had no idea how much of modern Western magic has grown out of the colonial fascination for exotic, magical India. What I loved most about this book is the respect that Zubrzycki gives to performers. We’re used to dismissing and disrespecting street performers, but Zubrzycki accords them grace by reminding his readers not only of the jadoowallahs’ distinguished past (and the way their standing in society suffered because the colonial administration was unnerved by them), but also the challenges they weathered like exploitation and racism. Also, this book has one of the most gorgeous covers.

*

If you're looking for shorter reads, may I direct you to my website? It has a few short stories and a blog where I put up random jottings as well as unedited versions of the column I write for the Mumbai edition of the Hindustan Times. The column I wrote on Made in Heaven and Captain Marvel have got a lot of love, which is always nice. If you spot any typos, let me know.

Open Culture is one of my favourite places on the internet and you'll be able to see why if you click on this link which is about of literary maps. With great enthusiasm, I bounded over to Amazon to check the price of Huw Lewis-Jones's book, A Writer's Map, which is the source material for this post. It costs more than $100. See why I love Open Culture?

Another website that almost always has something interesting is Literary Hub, like this essay on literary tricksters like Jeeves and this one on literary allusions in rap lyrics.

*

Dear Reader will be back soon. Thank you for reading.