The Dispossessed + A Gentleman in Moscow + New Books

“I never thought before," said Tirin unruffled, "of the fact that there are people sitting on a hill, up there, on Urras, looking at Anarres, at us, and saying, 'Look there's the Moon.' Our earth is their Moon; our Moon is their earth."

"Where, then, is Truth?" declaimed Bedap, and yawned.

~ The Dispossessed, Ursula Le Guin

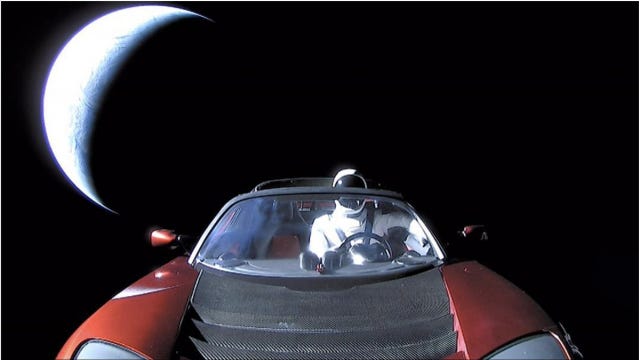

My trip around the worlds of Ursula Le Guin continues. With Elon Musk sending a car into space (with a dummy astronaut, “Starman”, at the wheel and Hot a Wheels on the dashboard), it’s weirdly fitting that I’ve spent most of the past week reading a novel about a society that sets up a colony on a moon. Right now, there is a car in space and this photo is not the cover of a sci-fi novel, but from the feed of the Roadster that is currently heading to the Asteroid Belt.

From Elon Musk's Instagram

Approximately 170 years ago, on the planet of Anarres, there was a rebellion led by an anarchist and philosopher named Odo. Eventually, an agreement was reached. Odo’s followers were given the moon. They boarded ships and left Annares to set up their anarchist colony on Anarres’s moon, Uras. The moon essentially became a prison, but one that promised freedom to those who would live on it.

Life on Uras is hard. The moon is habitable, but barely. Still, the settlers manage and slowly build a society without government, without private ownership and with freedom. Computers decide names. People do a variety of jobs, filling positions that need to be filled. In a cold and unforgiving habitat, a thriving society is built. Then, along come a group of young upstarts who aren’t blind to how the anarchist ideals of Uras and Odo are being turned into something more rigid and metallic. Hierarchies have formed, power is exercised by a few and while there are no laws, there are leashes. A physicist named Shevek starts feeling particularly claustrophobic on Uras because no one on his planet particularly cares for his research, but there are scientists and engineers on Anarres who are excited by his work.

And so, for the first time in almost 200 years, a man from the moon returns to the planet of Anarres.

The Dispossessed won the Hugo award in 1974. It’s a remarkable book because of the hive of ideas contained in it and Le Guin’s incredible talent for world building. The beauty of Le Guin’s world building is how subtly it’s done. She emphasises the strangeness of this new world she’s brought the reader to but by revealing it little by little, she teases and kindles the imagination. The descriptive bits — like snow swirling and catching the streetlights on windy, desolate Uras — are beautiful but I particularly love how cleverly Le Guin makes her characters toss little details about their world to the reader. The worlds of Anarres and Uras (like those in her other books too) are created with language, through the way certain words are used and the meaning they convey. Like “kemmering” in The Left Hand of Darkness or “profiteer” and “egoize” in The Dispossessed. Masterful stuff.

There’s a lot of Taoism and faux-science in The Dispossessed, which I will freely admit to having only pretended to understand. If Shevek says simultaneity makes sense, I’ll take his word for it, thank you very much. She brings in Einstein, who is “Ainsetain” on these planets, and touches upon his work as well. Again, I’ll take her word for it. At one point, Shevek meets someone from Earth and she tells him, “My world, my Earth is a ruin. A planet spoiled by the human species. We multiplied and fought and gobbled until there was nothing left, and then we died. We controlled neither appetite nor violence; we did not adapt. We destroyed ourselves. But we destroyed the world first.” In my mind, I saw Elon Musk’s floating Tesla with its Starman.

Theoretically, Anarres and Uras are both supposed to be ambiguous utopias, but the one weakness of The Dispossessed is that Le Guin doesn’t want to risk her reader falling for the “profiteering” world of Anarres. So she constantly reminds the reader of the maggots within the shiny apple —inequality is the fundamental upon which Anarres is built; women are second-class citizens and inferior to men; money decides everything and access to it has a lot to do with the social strata you were born into. The poor are good and the rich are bad. It’s all very black and white on Anarres. When people praise Anarres, they come across as blinkered and naïve because it’s so obvious that this is a deeply flawed and rotting society.

Uras is literally and figuratively much more grey. It’s pure in its idealism, suggests Le Guin, but there’s a rigidity that comes with this that is stifling. For me, Uras’s insistence upon insularity, the paranoia about communication with the world beyond is a massive flaw. Can you truly grow like that? Le Guin seems to suggest that even if this doesn’t work for the individual, the collective will thrive. I remain unconvinced.

*

Amor Towles’s A Gentleman in Moscow has the most gorgeous black and gold cover. Set in the 1920s, it’s about a confirmed aristocrat, Count Alexander Rostov who is placed under house arrest in the attic room of the Hotel Metropole, one of Moscow’s most elegant establishment. While he remains within these confines, Russia changes and through the revolving doors of the Hotel Metropole, people walk in to give Rostov snippets about what’s happening outside. A Gentleman in Moscow doesn’t get sucked into much socio-political commentary. For Rostov, there are certain things that are more important than the Kremlin — like pairing a dish with its complementary wine, getting his shave from the hotel’s barber, and generally holding on to the suave in face of all deterrents. The luxury of Metropole, even while its fortunes suffer, is a far cry from spartan Uras, but it's sort of interesting how both these novels suggest that being confined actually helps to open up the mind.

You wouldn’t expect a novel about house arrest to be funny, but A Gentleman in Moscow is just that. Rostov is a delightful dandy, with his waxed moustache (which gets savagely cut when the barber at the Metropole serves him before another man of the new elite) and love for people-watching. His commitment to being a Count in face of a changing world is endearingly ridiculous and eventually reveals the shine of a certain kind of valour. When the promises of the revolution are mangled and new cruelties are heaped upon Russia, it isn’t as though A Gentleman in Moscow laments the passing of the world order. Rostov is nostalgic, but very particularly for the life he had. His past life becomes is like a snowglobe in which selective memories have been preserved.

There’s a lightness to Towles’s storytelling that makes A Gentleman in Moscow a charming and easy read. He doesn’t dismiss pain and hardship, but as far his Rostov is concerned, wit, charm and sophistication are of primary importance; especially when a world is riddled with sorrow. Along the way, circumstances lead to Rostov becoming the guardian of a little girl named Sofia. It’s not an immediate friendship:

Never had the toll of a bell been so welcome. Not in Moscow. Not in Europe. Not in all of the world. When the Frenchman Carpentier faced the American Dempsey, he could not have felt more relief upon hearing the clang that signalled the end of the third round than the Count felt upon hearing his own clock strike twelve. Nor could the citizens of Prague upon hearing the church bells that signalled the end of their siege at the hands of Frederick the Great.

What was it about this child that prompted a grown man to count so carefully the minutes until lunch?

I loved how Towles lavished attention to Metropole’s luxuries and Rostov’s fripperies because he managed to convey simultaneously how precious it is to have beauty around you and how frivolous it may seem when the world is going to hell. His memories and rituals anchor Rostov in what he considers important. Politics aren’t irrelevant to the novel, but Rostov’s story is really about so many other things, not the least of which is parental responsibility. Of course, that by extension could be considered a scathing political critique considering Russian leaders’ obsession with being Fathers of the Nation, from Peter the Great to Joseph Stalin.

Fun read. Thanks to Trilogy, the lone bookstore of Lower Parel, for recommending this.

*

OUT IN FEBRUARY

Auroville: Dream and Reality

Edited by Akash Kapur

Penguin Random House, Rs 399

When a book is described as “polyphonic”, my radar for pretentiousness starts flashing manically, but perhaps it really is the best word for Auroville. This anthology of writing from the community, edited by a long-time resident and representing forty-odd authors of various nationalities, seeks to shed light not only on Auroville’s ideals but also on its lived reality. Includes fiction, essays, poetry, drama, cartoons and rare, archival photographs.

Why Am I A Hindu?

Shashi Tharoor

Aleph, Rs 699

This is apparently Tharoor’s attempt at reclaiming Hinduism from Hindutva. Starting with a close examination of his own belief in Hinduism, he goes on to consider schools of thought in Hinduism, aspects of Hindu philosophy and manifestations of political Hinduism in the modern era.

Westland’s new imprint, Context, has a list of very good-looking titles coming out this month. Take a look:

Poonachi or The Story of A Black Goat

Perumal Murugan (trans. N Kalyan Raman)

Fiction, Rs 499

A comment on identity and difference, on liberty and resistance, on the female condition and of empathy with the animal world. Evidently not light reading. At some point, I hope someone can explain to me Malayalam literature’s love affair with goats.

An Ordinary Man’s Guide to Radicalism

Neyaz Farooquee

Non-fiction, Rs 499

Described as a vivid exploration of what it’s like to be a Muslim in India, Farooquee examines how stereotypes are cemented by institutions like the media and the police. The book looks at both rural and urban India.

Peace Has Come

Parismita Singh

Fiction, Rs 499

A collection of short stories set in Assam’s Bodoland. Contrary to the title, peace isn’t exactly what follows ceasefire.

In Pursuit of Conflict

Avalok Langer

Non-fiction, Rs 399

A journalist’s diary of reporting from the Northeast, this book includes interviews with separatist leaders, encounters with drug cartels and other voices that are rarely heard.

Indira

Devapriya Roy & Priya Kuriyan

Creative Non-Fiction, Rs 599

If Priya Kuriyan is illustrating something, buy it. This is a biography of Indira Gandhi and I’m not sure why it’s been described by the publishers as “part fiction”, but it promises us a warts-and-all look at India’s only woman prime minister so far.

*

Dear Reader will be back next week with more nattering on books. Thank you for reading.