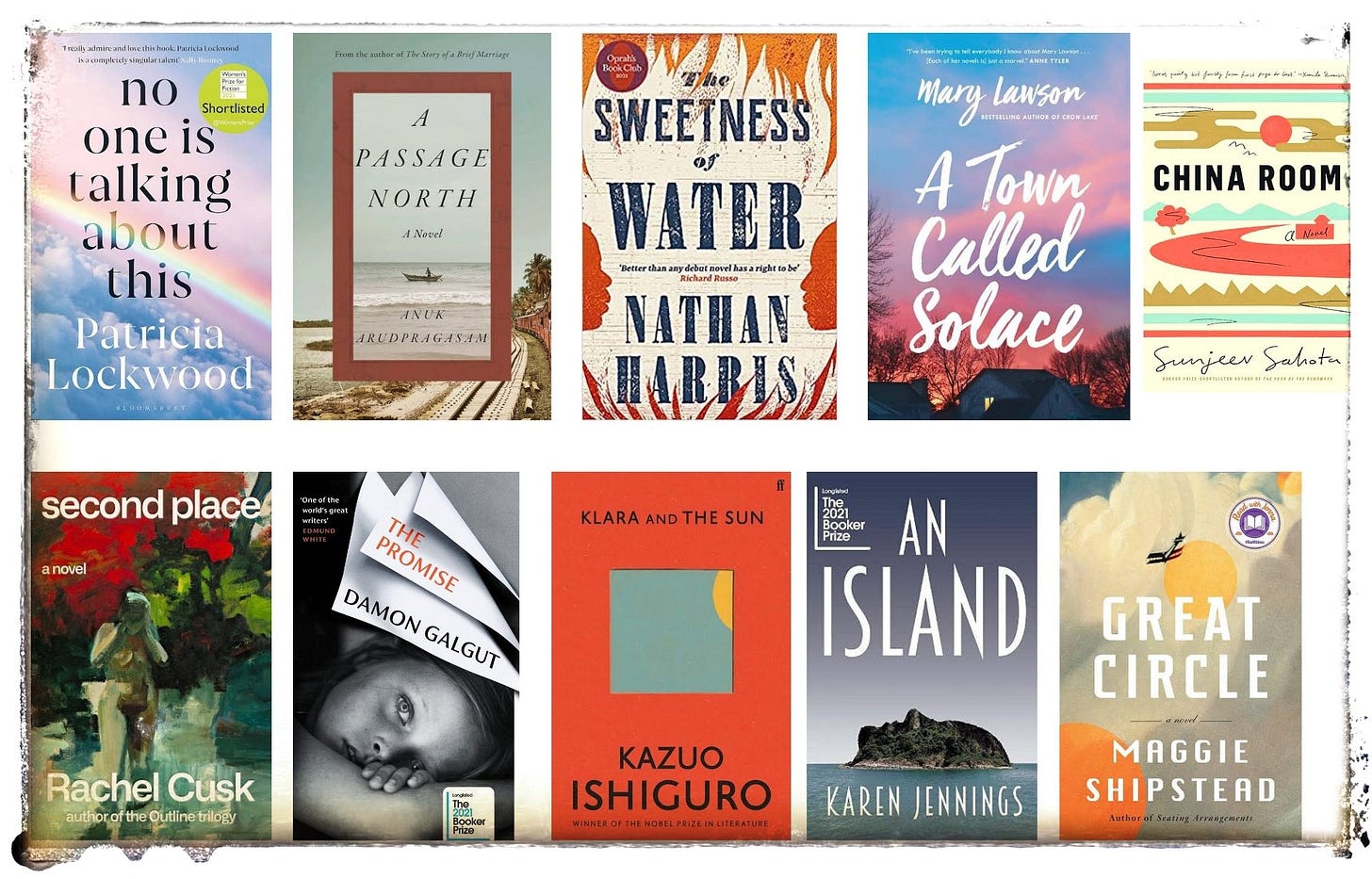

The Booker longlist

A couple of weeks ago, my Kindle suddenly refused to acknowledge my home wifi connection. When I scanned for wifi networks, it showed me three neighbours’ connections, but not my own. Not even my phone’s personal hotspot would register even though the phone was right there, next to the Kindle. Have you seen Eddie Izzard’s sketch about printers?

Replace printer with wifi and computer with Kindle, and you have me. Nothing worked. I tried the age-old tactic of restarting the damned thing. I even reset the device — thus losing access to my whole Kindle library. Insert wail here — but to no avail. As far as my Kindle is concerned, the only network worth connecting to is the network that I can’t access.

(I live in hope that this is not a message from the universe.)

I blame my current woes on Sunjeev Sahota’s China Room. I believe my Kindle is punishing me for not abandoning this novel despite my lit fic radar recognising within 20 pages that this book would go downhill. Ostensibly drawn from Sahota’s own family history, half of China Room is set in the late 1920s, when 16-year-old Mehar’s life changes after an arranged marriage. She’s married to one of three brothers, each of whom has had a bride selected for them by their mother. From a carefree childhood, she finds herself in the claustrophobic confines of her marital home, where a cruel matriarch crushes the joy out of every situation. Running parallel to Mehar’s story is that of her great-grandson, an unnamed, young British Asian man who comes to live with the Indian branch of his family in a village in Punjab instead of going to rehab in England. The idea of rehab in Punjab, where heroin addiction is an epidemic, is darkly hilarious, but I’m guessing things were different in 1999. Not that you get any sense of what rural Punjab was like in 1999 from China Room. All our narrator is concerned with are his withdrawal symptoms and the crush that he develops on a doctor working in the area.

Mehar’s story is the more interesting one and China Room may have been more satisfying if Sahota had focused on reimagining her life with a little more depth. It doesn’t help that the writing includes details like how on one occasion, the dupattas that the women use to cover their faces snags on Mehar’s eyelashes. Because you know how it is with us gorgeous Indian damsels and our projectile eyelashes.

This is when I should have stopped reading because there is no way my sensibility is ever going to sync with someone whose idea of lyricism and beauty is a dupatta getting caught on eyelashes. But I tempted fate and kept on reading, and the novel got worse. China Room is one of those books that you know could have been a powerful saga, but by the end, all we’ve got is a dissatisfying novel that feels rushed and contrived. Every character is drawn in broad strokes and the details are either lacking or feel jarring. For instance, why would a Punjabi family, in a village in Punjab, speak Hindi? Why is a Sikh person invoking Krishna? And don’t even get me started on the dark room to which Mehar and her sisters in-law are sent to have sex. It seems the mother in-law doesn’t want the three wives to know which of the three brothers they’re married to, which is bizarre in itself, but more importantly, surely there are ways to differentiate one naked man from another even if you can’t see in the dark. Also, the china that gives the book its title is a throwaway detail so in case you picked China Room up hoping for some pottery stories, keep moving.

If China Room makes it to the Booker shortlist… I will roll my eyes and go on with whatever I was doing because I’m way past that rosy stage of optimism when one believes prizes and awards are all about merit. If you like melodrama in your literary fiction (as the Booker Prize judges evidently do), this may be the book for you, but I wouldn’t recommend China Room to anybody. It’s the only major disappointment for me so far in the Booker longlist and I’ve read 10 of the 13 longlisted titles. The ones I haven’t read are Bewilderment, which isn’t out yet; The Fortune Men, which costs Rs 578 on the Kindle (it was some Rs 700 a fortnight ago. I’m hoping the price comes down to ‘normal’ if it’s shortlisted); and Light Perpetual, which I might pick up next.

For most part, it’s been an absolute joy to make my way through the Booker longlist. Usually, extended exposure to literary fiction leaves me feeling prickly. For all its beauty, even when it’s written well, literary fiction can feel laboriously arty after a point and it’s committed to being depressing (because happy endings aren’t Literature or Art, as per the canon). But with this year’s Booker longlist, I dived into one book after another without a stumble. One of the things that makes the Booker lists special is that there’s a range of countries and cultures reflected in the selected books, which means you get a sense of how the same English language sounds different in stories from around the world. For instance, the English in A Passage North —which is set mostly in Sri Lanka and explores the terrible legacy of the civil war with quiet grace — has a different cadence and rhythm to it than the English of Second Place. There are some details in Second Place that felt pretentious and the novel collapses like an unsuccessful soufflé after the climax, but mostly, it’s witty and weird, which is a charming combination. The Sweetness of Water is a strong debut novel, set in America right after its civil war. You can glimpse some classics of modern American fiction as the novel comes into its own, following the lives of two recently freed men and a white landowning couple. A Town Called Solace is one of those rare books of literary fiction that is actually hopeful and has a happy ending. It’s not unputdownable, but it’s very satisfying. Also, a small town that isn’t riddled with sadness or dysfunction is a refreshing change. I’ve written about Klara and the Sun in a previous newsletter and you already know how I feel about China Room.

My current favourites from the longlist (in the order that I’ve read them) are:

The Promise by Damon Galgut

An Island by Karen Jennings

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead, and

No One is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood.

In case you’re wondering why there’s no link for An Island, there’s no Indian edition available for this book at the moment. I came across it while trawling through Goodreads, where I read this quote by Jennings, a South African author, about the time when she was writing the novel and it made me very curious about An Island:

“I was alone for 10 hours a day in an apartment on the 17th floor of a tall apartment block. I hardly went anywhere. I saw no one but our building’s security guards. When I did meet people, I was unable to have any sort of conversation with them as I knew very little Portuguese and had no opportunity to practise …. I became obsessed with the order of things – everything had its place and time – and I became unsettled when my husband disrupted that order. In my mind, he began to feel like an interloper.”

So I confess, I dug into somewhat dubious resources to get hold of this book and I’m still feeling guilty because the publisher is a tiny, indie outfit. If I’m ever able to access this book un-dubiously, I will buy multiple copies — partly to assuage my guilt but mostly because it’s such a good novel. An Island is set, unsurprisingly, on an island which has just one inhabitant: its lighthouse keeper. When a refugee washes up on the beach, the lighthouse keeper has to figure out what to do with the newcomer. As the two men try to come to a workable arrangement, the lighthouse keeper remembers episodes from his past, recalling his own turbulent history and that of his country. An Island is about power, politics, racism, poverty and the postcolonial nation — dense topics that are woven skilfully into a narrative that offers a sharp and pointed contrast to the Robinson Crusoe template of a man stranded on an island.

Damon Galgut’s The Promise looks at a lot of the same topics, but in a very different story and setting. His novel is about the white Swart family, which owns a farm outside Pretoria, and we see how the family members and their fortunes change as South Africa comes out of the apartheid era. The title refers to the promise a four-year-old Amor heard her dying mother extract from her father. Amor’s mother wanted the Black maid Salome to be declared the legal owner of the small patch of land on which Salome lives at present. Amor’s father promises to do so, but after Amor’s mother dies, that promise is deliberately forgotten by everyone but Amor.

Galgut’s writing is magnificent and I would share excerpts with you to show you what I mean, but thanks to my cursed Kindle, I don’t have access to any of my e-books or the many sections I highlighted in The Promise. Galgut’s language is precise and beautiful. There’s not an extra word or sentence anywhere and perhaps his most amazing feat as a storyteller is the way he shifts from the perspective of one character to another in this novel. Conventionally, an author is expected to pick one out of the three kinds of narrators. There’s the first person narrator, showing you the world from a subject’s point of view; a second person narrator, who collapses the boundaries between reader and subject; and a third person narrator, who offers a more omniscient approach to the narrative. In The Promise,Galgut flits from a third person narrator to first narrator with breath-taking elegance. As a reader, it feels like you’re haunting these characters, slipping into their heads and then slipping out to see the room they’re in and the world around them. These literary tricks can feel confusing and gimmicky, but Galgut makes it work. I found myself re-reading sections even before I’d finished the book, just to admire the way he’d gone from one character to another with just a word or half a fragment. This is a book that I’d get a hard copy of so that I can underline and annotate the heck out of it.

Another writer who makes masterful use of a writing technique that is bound to be a disaster in the hands of the less capable is Patricia Lockwood. Much of No One is Talking About This is written in fragments to reflect the scattershot way of thinking that comes from social media (particularly Twitter), where posts on different subjects stack up one after the other and push us to flit manically from one idea to another. Particularly in the first half of the book, Lockwood’s narrator — who seems to be a somewhat caricaturish version of herself — jumps from one thought and moment to another as she goes through “the portal” that is social media. Each paragraph seems to be disconnected from what comes before and after, which can feel disorienting and is (I think) intended to be that way. Lockwood is frequently funny and consistently insightful as she writes about how we behave on the internet, the adrenaline rush and frenzy of the hive mind, the way we use language when writing on the internet, and how online behaviour influences offline lives.

The second part of the book is rooted deeply in the real world of offline life, after the narrator and her family are faced with a terrible crisis. Her sister is pregnant with a baby who is not likely to survive. She can’t get an abortion because of the laws in her state and when the baby is finally born, the axis of their lives tilts. The two parts of No One Is Talking About This are so different that by the end, they almost feel like two separate books. This may seem like a flaw at first, but I think it’s intentional. Lockwood wants to give her reader an emotional whiplash. Somehow, Lockwood has managed to write the Twitter novel that reflects our times as well as a heartbreakingly poignant story about survival, love and grief — in one book.

Perhaps the most conventionally written of my longlist favourites is Great Circle, by Maggie Shipstead, about two women celebrities who are connected by the stories told about them. One of them is an actress, named Hadley, who is the star of a successful film franchise and a paparazzi favourite. After a scandal leads to her being dropped from the franchise, Hadley decides to star in an indie-ish film about an aviator named Marian Graves who lived through the Prohibition era, World War II and finally disappeared while trying to circumnavigate the globe. Marian and Hadley are both fictional, but the worlds they inhabit are and feel tangibly real. From entrepreneurs like Jaqueline Cochran, who was the wartime head of the Women Airforce Service Pilots, to folklorish figures like Sitting-In-the-Water-Grizzly, and a Hollywood film producer who makes you remember all those #MeToo stories, Great Circle is full of references to real people and events. There’s a lot that Shipstead has packed into this novel and she’s created some fantastic characters, like Marian and her husband, the bootlegger and rancher Barclay Macqueen. I think what I loved most about Great Circle was how Shipstead’s characters create facades and personas for themselves as they try to figure out who they are and what they want from life.

I should stop now. This newsletter is plenty long even by my standards. Please say a prayer for my Kindle so that sooner rather than later, it wakes up to the fact that there is wifi in this apartment.

I hope you’ve been well and the world is showing you kindness. Thank you for reading and Dear Reader will be back soon.