Reading 400 Pages in a Day?

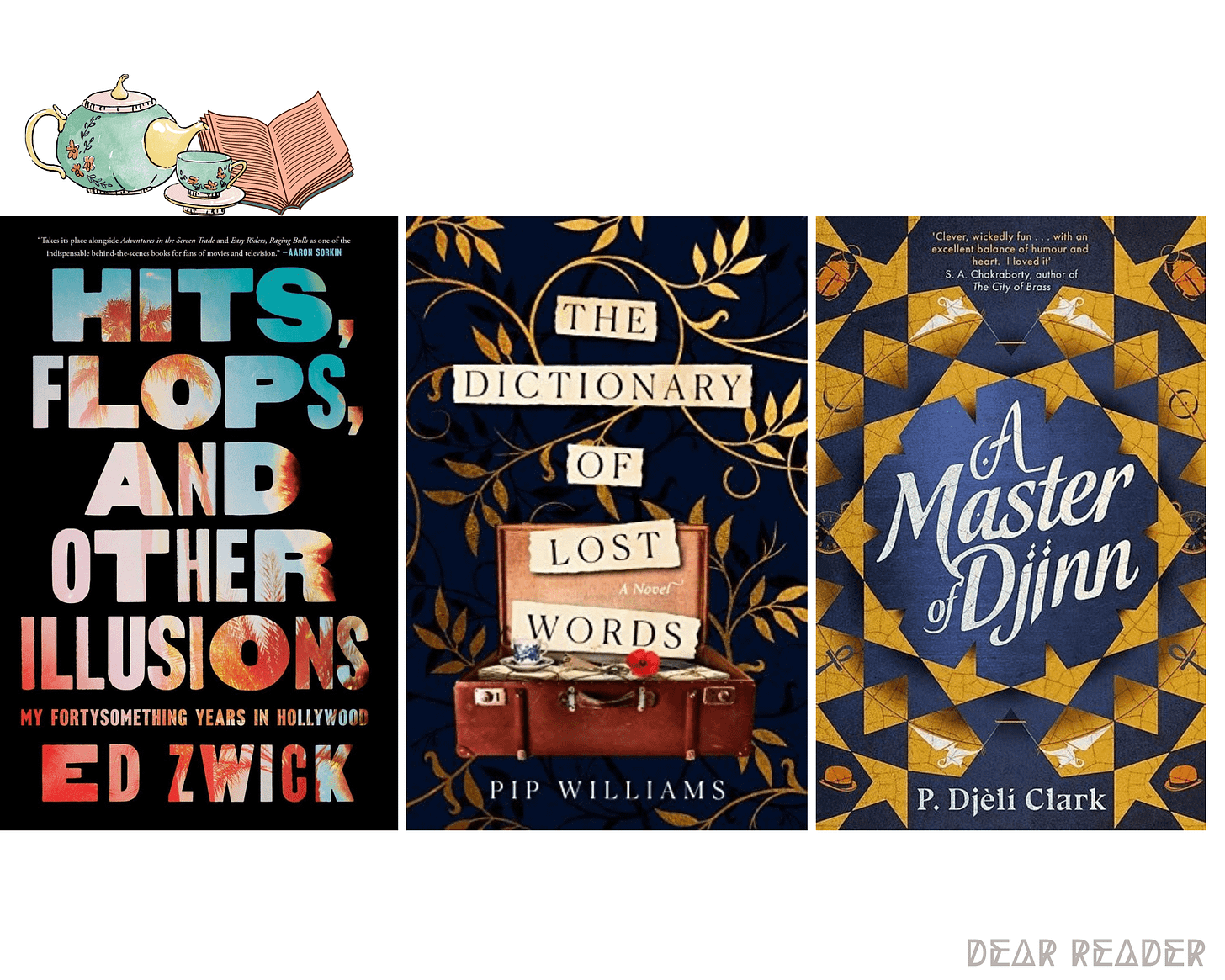

Dictionary of Lost Words • A Master of Djinn • Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions

I thought I was having a decent reading spell when I finished writer, director and producer Ed Zwick’s memoir, Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions in about 10 days. It’s a big fat book that doesn’t feel weighty because Zwick shares some delightful Hollywood stories that range from gossipy to earnest. He talks about ego tantrums by stars (Matthew Broderick’s mother was a nightmare to work with. Julia Roberts derailed a film because she wanted her co-star to be Daniel Day Lewis and he wasn’t available), shares zingy snippets (Brad Pitt’s main concern during an intimate scene was the make-up for his butt), and is one of those people who can talk about directing Tom Cruise, Daniel Craig and Leonardo DiCaprio (among others). Zwick’s credits include films like Shakespeare in Love, Glory, Blood Diamond, and Love and Other Drugs. With names and titles like that, it’s no wonder the 400-odd pages don’t feel like a drag.

Plus, having begun his career as a journalist, Zwick is good at writing in a way that steers clear of self-indulgence (until the last chapter). Something’s always happening in Hits, Flops, and Other Illusions and each chapter ends with a list that makes points which are sharp and funny, and is a tongue-in-cheek concession to anyone who wants this memoir to serve some educational purpose. Also, Zwick admits to mistakes, which is rare for anyone of his stature to do these days. However, this doesn’t mean he has perspective on The Last Samurai, which Zwick wrote and directed. He’ll have you know the film made big money in Japan (never mind the cringe-inducing white saviour complex) and thanks to it, Ken Watanabe got his big break after a bad spell, which saw him landing in debt with the Yakuza no less. The more fascinating part of that chapter though is to see what goes into making a Tom Cruise film, from studios cheerfully spending millions of dollars to Cruise photoshopping himself into a photograph. To quote Zwick, “Apparently, even movie stars have FOMO.” Good to know.

So yes, I finished that tome. Then today, I sat down to do some reading for an assignment I’ve taken on because I’m an idiot and Reader, it did not go well. At one point, I realised it had taken me 90 minutes to wade through 10 pages. Just to give myself a change of pace, I thought I’ll read something else and then get back to the work reading. Next thing I know, the day is over and I’ve read the whole book. By which I mean 400 pages. In a single day. All because Pip Williams’s The Dictionary of Lost Words is just that wonderful. I haven’t read something with this kind of compulsive delight in ages. Which is why here I am, at midnight, sitting down to write this newsletter to tell you that if you’re someone who likes stories about history, language, power and sisterhood, then Williams’s novel is for you.

In her author’s note, Williams writes that the idea of The Dictionary of Lost Words came to her after she read a book that she enjoyed, but which left her with a question: “Where, I wondered, are the women in this story, and does it matter that they are absent?” The story she’s referring to is the creation and compilation of the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). Through the prism of the fictional Esme, Williams puts together the history of an extraordinary endeavour while also celebrating the smaller, everyday triumphs of women’s lives in 19th century England.

Esme’s earliest memories are of sitting on her father’s lap, looking at the slips of paper that have on them words submitted for the OED. Her father is part of lexicographer James Murray’s core team, who work in the Scriptorium and sift through the countless words in circulation to decide what will make it into the first edition of the iconic dictionary. From the words that are discarded or dismissed — there are stringent criteria for a word to qualify as worthy of an entry in the OED — little Esme starts putting together her own dictionary by sneaking out the slips with words that wouldn’t make the cut. The casual, slightly-klepto hobby turns into a secret passion project when Esme realises that Murray’s dictionary won’t accommodate many words that are part of conversation, but not considered worthy of polite society or being published. Without any plan in mind, Esme goes around Oxford collecting words, mostly from working women of different kinds.

Considering Williams’s starting point, there are (predictably) many wonderful women characters. Some of them are drawn from history, most are from the author’s imagination. The heroine of The Dictionary of Lost Words is unusual for being someone who doesn’t want to stand out. Repeatedly, we see Esme sit in the wings or stand at the fringes of a high-profile gathering. She watches and takes notes, rather than actually doing things or even speaking up. Bookish, curious, carrying the weight of many sadnesses despite her privileged upbringing, Esme sees herself as a witness, rather than a protagonist who must claim centrestage for herself. As her godmother writes, when describing Esme in a letter, “This is what she did, you see: she noticed who was missing from the official records and gave them an opportunity to speak.”

There’s an episode early on in The Dictionary of Lost Words when Esme has a terrible experience in boarding school (the subtlety with which Williams reveals this to the reader is brilliant and masterful). Esme is sent away from home because those who love her want to make sure she gets a good education so that the world opens up for her in a way that it didn’t for women in previous generations. However, the move turns out to be a terrible misfire, reminding the reader that privilege and opportunity didn’t always protect girls from cruelty and trauma. Her boarding school experience makes Esme shrink into herself and even when she does emerge from her shell, Esme remains cautious and careful about every step she takes. Grappling with both her personal experiences and history, Esme’s the kind of person who fades from record — until she’s phoenixed back to life by an imagination like William’s.

I loved Esme’s relationships with her godmother Edith and Lizzie, who works as a maid in the Murray household and is young Esme’s nanny. Their bonds go through the push and pull of life, fraying with tension at times, but ultimately holding steady. Incidentally, Edith and her sister are based on two real women who contributed greatly to the OED. Williams also takes care to create a set of minor characters who get shades and nuances, like the foul-mouthed crone Mabel (who introduces Esme to the word cunt, among other things) and the flower-seller who has her shop right next to Mabel’s stall.

From Studio Joyeeta.

Alongside this dazzling cast of women, who feel entirely real and relatable, are some wonderful men. From Esme’s father, to the charming playboy she encounters as a young adult, the cantankerous printer who struggles to hold on to his workforce when World War I breaks out, the lexicographers in the Scriptorium, and the man Esme falls in love with, The Dictionary of Lost Words is full of gents who are easy to adore. It also has perhaps the most perfect and romantic proposal for a bookish person. I properly aww-ed, out loud, in my living room. It feels important to point out how Williams has written the men in the novel because a lot of people seem to be under the misconception that a “woman-centric” novel is one that pays no attention to anyone other than the women characters. Fortunately, The Dictionary of Lost Words isn’t burdened by such dullness.

When the novel was nearing its end and had become lopsided in my hands, one side neatly fitting between my barely-parted fingers while the other needed my hand to stretch to contain its pageload, I couldn’t help but wonder how Williams was going to end this story. I peeked at the title of the epilogue. It read “Adelaide, 1989.” My eyebrows rose with disbelief. It seemed a bit of a stretch since I was minutes away from the epilogue and the page I was on was about shellshocked soldiers from World War I. Let me just say that Williams finds the most charming way to connect Esme’s history to 1989. When I reached the last line of The Dictionary of Lost Words, I had a smile and a full heart.

My other excellent recent read is A Master of Djinn, which technically belongs to the fantasy genre, but really, it’s crime fiction. Set in an alt-reality in which magical creatures are part of regular society, A Master of Djinn is set in a steampunk-ish Cairo. It’s 1912 and Egypt is a kingdom that has thrown off the Ottoman yoke, thanks to an alliance of the human and the supernatural. When the members of a secret cult are killed in a horrific way that defies logic, agent Fatama el-Sha’arawi from the Ministry of Alchemy, Enchantments and Supernatural Entities is put in charge of the case.

From angels to ifrit and ancient Egyptian gods, A Master of Djinn is teeming with magic, but to P. Djèlí Clark’s credit, most of these supernatural creatures are imagined in a way that runs counter to the way they’re usually depicted. Angels, for example, are not beatific creatures, but rather gleaming, unnerving beings who leave you feeling unsettled. From the geography of his Cairo to the details of the creatures that inhabit it, I loved Clark’s worldbuilding. There’s no spoonfeeding or lazy exposition. Instead, he drops the reader in the middle of this world and lets it reveal its otherworldliness to the reader at an elegant, steady pace.

Fatama, with her sharp three-piece suits and cane, is a charmer. Standing by her, shoulder to shoulder, is Hadia, the partner whom Fatama initially doesn’t want because she’s used to working along. Unsurprisingly, the two end up getting along and make for an excellent buddy-cop duo. The two women are two kinds of modern Muslima — smart, ambitious, independent and quick-witted; one with hijab and prayers, while the other flouts conventions. The differences don’t get in the way of their eventual camaraderie. Fatama’s other ally is the mysterious Siti, who shimmers with enchantment and seems to have a special connection with the Egyptian goddess Sekhmet.

In this magical Egypt, magical creatures and different faiths live side by side, but the presence of the supernatural doesn’t mean there isn’t tension in society. The Cairo of Clark’s djinn-verse is grappling with inequality, prejudice and ghettoisation. Europeans are hovering around Egypt, eager to profit from it, and the poor in cities like Cairo feel increasingly desperate. The simmering tensions are brought to the surface when the murder that Fatama is investigating leads her to someone who claims to be al-Jahiz, a messianic figure who disappeared after ripping open a boundary between the magical and the mundane. The new al-Jahiz claims he’s returned to lead the downtrodden to revolution and glory. He also freely confesses to having committed the murders Fatama is investigating. Which is all very well, but al-Jahiz is too powerful for Fatama, even when she has Siti and Hadia by her side. He also has a dangerous new gift: he can control djinn and make them do whatever he commands. If the humans and djinn have to go up against one another, it would be civil war.

A Master of Djinn is a solid police procedural, albeit with djinn, enchantments, and humans who have something of the divine in them. As always with good genre fiction, there’s an exploration of many ideas that are grounded in contemporary reality rather than fantasy. Clark’s day job is in academia — he’s a professor of history — and that rigour and research adds a richness to the characters and relationships he’s created in this fictional world. Notions of femininity, a critique of the Orientalist perspective, and an exploration of what it means to be robbed of personhood are just some of the ideas that layer the murder mystery in A Master of Djinn. I thoroughly enjoyed it as much for the way Fatama played detective as for the beautifully-imagined world that weaves together so many different strains of folklore, legend and myth to create something that’s distinctive and unique.

Ok, it’s 1.55am now, which seems like a good time to wind up and wind down. Thank you for reading, and Dear Reader will be back soon.

I will definitely be checking out The Dictionary of Lost Words! I find I so rarely have that feeling I did when I was a kid, that I can't stop reading a magical book and am mesmerized, and I'm chasing that feeling lately.

Always look forward to your newsletter and recommendations and The Dictionary of Lost Words sounds like such a brilliant read!