Last month, when the shortlist for the Booker prize came out and multiple fireworks exploded in my skull, I was all set to rant in this newsletter about prizes, shortlists, and literary merit. One month and three excellent novels later, I remain mystified by the reasoning that guided the Booker prize’s jury, but do I give two hoots about its (or really, any other literary prize’s jury’s) attempts to be relevant and a conversation-starter? No. Authors benefit from shortlists and prizes; not books. Bad books will not improve in quality just because they’ve been shortlisted or won a prize. Good books will remain good books whether or not they’ve been shortlisted for or won prizes. (Hashtag: Zen and the art of Literary Criticism.)

You’d think that writing about books I’ve enjoyed would be easy and sometimes, it is. This, however, is not one of those times. My brain appears to have lost all capacity to formulate complete thoughts. I would like to blame this on Kolkata’s disgusting humidity (anyone who waxes eloquent about “autumn” in this sweaty town, consider your ears boxed by yours truly) or it might be that my brain has been squished under the weight of the massive meals I seem to be eating every hour. Whatever the reason, stringing coherent sentences is currently not my forte, but here we are. Bear with me.

I didn’t plan it this way, but the three books that stayed with me this past month all explore how confinement, solitude and trauma can impact people. First up: Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, which for me is the book of the year. Also, guess what? It’s actually not premature to declare a book of the year. There are less than 80 days left to 2020.

Coming back to Piranesi. This is a weird, beautiful little novel about magic, solitude, healing, trauma, bullet journalling (I kid you not. A key revelation in the book comes from a character maintaining an index of subjects they’ve written about in their journal, which as BuJo as a BuJo gets)… and so much else. I don’t think knowing the plot adds much to the experience of reading Piranesi, but I would recommend spending a little time with the works of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, an 18th century artist from Italy who is best known for his etchings of imaginary prisons. (You can also see an animated ‘tour’ here.) Piranesi drew sinister but beautiful spaces, with grand architecture and a distinctly Gothic feel. They looked like labyrinths that appear in nightmares, from which you can’t escape. Here’s a detail from one of his prints:

In Clarke’s novel, the hero lives in a sprawling structure that he calls the House and which could be one of Piranesi’s imaginary prisons. This is why he’s nicknamed Piranesi by the only companion he has in the House. The H is capital because the House is a world unto itself, holding its own against time and the rushing tides of a surrounding sea. “It is my belief that the World (or, if you will, the House, since the two are for all practical purposes identical) wishes an Inhabitant for Itself to be a witness to its Beauty and the recipient of its Mercies,” Piranesi tells us early on in the book.

Imagine a prison that manifests prisoners to stand witness to itself. Imagine prisoners who turn a prison into a sanctuary by the sheer force of their perspective. Imagine a world that became a prison because those who visited it could not find a way out.

Near the end of the novel, we’re told that in ancient times, nature and man were not adversaries, but engaged in dialogue: “Seas could be parted, men could turn into birds and fly away, or into foxes and hide in dark woods, castles could be made out of clouds. Eventually, the Ancients ceased to speak and listen to the World. When this happened, the World did not simply fall silent, it changed.”

Clarke doesn’t specify what time period Piranesi is set in — the sections in the House are literally timeless — but there are indicators that the world beyond the House is a modern one, made cutthroat by human ambition and noisy by progress. The tension between modern progress and ancient mysticism in Piranesi reminded me a little of JRR Tolkien’s worldview (much of the legendarium of Middle Earth was Tolkien channelling his disgruntlement at industrialisation into fiction. So all the good guys — like the elves and hobbits — live off nature peacefully while the bad guys go around ripping trees out and making death machines. Director Peter Jackson showed this very nicely in his movie adaptations).

At one level, Piranesi is a fantasy novel about ego and the quest for a certain kind of magical knowledge. At another, it’s a thriller about people who have gone missing. At yet another level, the novel is an allegory for certain mental health issues. (Clarke suffers from chronic fatigue. Readers have found parallels to multiple personality disorder, depression, bipolarity and more.) At every level, Piranesi is gripping and beautifully written.

What I loved most about Piranesi was the complexity that Clarke added to the idea of a sanctuary. She’s someone who clearly understands the restorative powers of silence and solitude. Some of the most enjoyable parts of the novel are descriptions of Piranesi on his own in the House, which is a prison of sorts, but it is also a cocoon out of which our hero emerges stronger and wiser (when he is finally ready to return to the world beyond the House). More than one character returns to the House and doesn’t want to leave it. More than one character takes upon themselves the task of dragging out someone who has gone in voluntarily.

“I know that she returns to the labyrinth. Sometimes we go together; sometimes she goes alone. The quiet and solitude attract her strongly. In them she hopes to find what she needs.

It worries me.

‘Don’t disappear,’ I tell her sternly. ‘Do not disappear.’

She makes a rueful, amused face. ‘I won’t,’ she says.

‘We can’t keep rescuing each other,’ I say. ‘It’s ridiculous.’”

You know, though, that rescuing each other is exactly what they’re going to do because the House, for all its dangers, can be restorative. (And no, I’m not going to tell you who “I” and “her” are.)

In Leesa Gazi’s Hellfire (translated from Bengali by Shabnam Nadiya), the place of confinement is the middle-class home. Lovely and her younger sister Beauty have all that they could possibly need — their own rooms, a TV and VCR, home delivery of joints — but their every every move is regulated by their mother, Farida. On Lovely’s 40th birthday, Farida is uncharacteristically generous: she gives Lovely permission to spend a few hours outside the house, alone. A stunned but delighted Lovely goes shopping, wanders around in a park, breaks her curfew and lets a man follow her home when she ultimately makes her way back. While Lovely flexes her new-found muscle of freedom, Beauty fumes at having missed out on a trip outside the house and Farida frets over a phone call from an old family friend.

Gazi, who is British-Bangladeshi, edges every banality — from Farida yelling at the maid to Lovely’s encounter with a creep in the park — with menace. The net result is that Hellfire reads like a thriller. The past, where old lovers and taboo memories are buried, haunts the present. Almost every character has a secret they’re guarding fiercely and their paranoia at being discovered sets off a chain of reactions that culminates in a chilling climax.

Bengali literature has a rich tradition of stories about domesticity that spotlight women (many of these are written by women) and Hellfire is a fine addition, but with a twist. Gazi’s novel also reminded me of the stories from English literature, like The Yellow Wallpaper and Wide Sargasso Sea, that explore how some women snap when straitjacketed by convention or circumstance.

Hellfire is a story about women and patriarchy, in which the men are few, marginal and powerless. It’s a reminder that rather than individuals or genders, patriarchy is toxic because of the ideology (with its rigid definitions of virtue, manliness etc) that defines it. Farida is a matriarch who has taken it upon herself to conform to the demands that patriarchal society makes of women and men. Through her, a hierarchy is established and maintained in the household — the ‘servants’ will serve; the weak man will stay on the margin; the obedient will be rewarded; those who raise questions will be punished.

Lovely and Farida are wonderful, complex characters who resist being categorised as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’. Also fascinating are Farida’s husband and the imaginary man in Lovely’s head, both of whom are like alter egos of the women they shadow. It makes sense that the imaginary friend Lovely would make up would be a man, given the dominant women she’s surrounded by, but it’s the parallel with her father that I found intriguing. Farida’s husband is almost an absent presence in the family much like the male voice in Lovely’s head. Once, in another lifetime, Farida’s husband had nudged his wife towards transgression. Similarly, Lovely’s imaginary friend also urges Lovely to live — and love — a little. When Lovely comes into her own in the final scene of Hellfire, the man in her head is as silent as her father is in the present.

Gazi wrote the original novel, Rourob, about a decade ago and you can read more about her in this profile.

And with that, ladies and gents, we reach the last book for this newsletter…

I started reading Colum McCann’s Apeirogon for no reason other than the way the English alphabet is organised: it was on top of my pile of unread e-books by virtue of the title starting with A. When I looked McCann up later, I found out that he’s been accused of sexual assault and the way he has written about Palestine in Apeirogon has been sharply critiqued by writer Susan Abulhawa, who provides great perspective in this essay where she says that despite McCann’s intentions and research, the novel does Palestine a disservice. Abulhawa questions the stories that make it into Apeirogon and what it means to empathise with Israeli characters in a book about Palestine. For instance, she points out that McCann doesn’t mention that Jewish Israelis who can trace their lineage in Palestine before World War II (like one of the two protagonists of Apeirogon) are not representative, but a minority. Meanwhile, so many Palestinians whose families have lived there for hundreds of years were forced into exile by Israel.

Apeirogon is based on the true story of a friendship between an Israeli and a Palestinian. Rami Elhanan and Bassam Aramin are fathers who have each lost a daughter — Rami’s daughter was killed in a blast by a suicide bomber in 1997; Bassam’s daughter was killed by an Israeli soldier in 2007. Both men joined the Parents Circle, a support group for those who have lost family to the senseless violence that is the norm in Palestine, thanks to Israeli occupation. Interspersed with the two men’s stories is a wealth of trivia — did you know the Hebrew word for pomegranate is also the word for grenade? — that is carefully arranged to talk about violence, freedom and identity. As a hat tip to One Thousand and One Nights (or Arabian Nights, as some call it), Apeirogon has 1,001 chapters. In the original collection of linked folk tales, the framing story is of a princess who tells these tales to save her life. In Apeirogon, instead of a princess, what the stories keep alive is the hope of friendship.

Opinion on both Apeirogon and Abulhawa’s critique seems to be divided in the Palestinian writing community, but I’m glad I read Abulhawa soon after starting the novel because it made me alert to nuances I wouldn’t have noticed on my own. That said, I don’t entirely agree with her critique. For instance, I don’t think Apeirogon gives Israel and its Army the free pass that Abulhawa argues it does. The novel reminds the reader repeatedly that Palestine is occupied and that the might of Israel’s state machinery can’t be compared to what the Palestinian resistance can access. However, Apeirogon does strive to make a distinction between Israelis who stand opposed to their government’s occupation of Palestine and the Israeli state, and Abulhawa has little time for such niceties. “No measure of understanding that Israelis ‘have families too’ will ever compel me to accept forced exile,” she writes, and while that may be a personal opinion, it is also fair. Perhaps the distinction between oppressive state and helpless citizen that McCann makes in his novel is one that I can accept smoothly because I’m a citizen of a state that has its own coloniser’s baggage, given India’s post-independence history of gobbling up Sikkim, placing vast stretches of the North East under oppressive military rule, and attempting to colonise Kashmir.

Reading Apeirogon often felt like putting my eye to a kaleidoscope. In each chapter, the words settle like pieces of coloured glasses into images that are often hauntingly, heartbreakingly beautiful. Like this one:

“One afternoon, in the Dheisheh refugee camp south of Bethlehem, Bassam watched four boys in white jeans and white T-shirts carry a single mattress past the low houses. They moved carefully through the narrow alleyways with the mattress propped high on their shoulders. Placed on top of the bed were four red carnations, arranged in a neat row.

It took him a moment to realise that the boys were in rehearsal for carrying a bier.”

Matching the elegance of the prose is the structure of the novel. I don’t know how one maps a novel like this, but somehow, McCann did. The spine of Apeirogon is made up of Bassam and Rami’s lives as a Palestinian and Israeli in Palestine. Wrapped like nerves around this spine are stories from a dizzying range of sources. Bird migration routes; folk tales; Francois Mitterand’s last meal; the quest of a mad missionary; Philippe Petit’s high wire walk across Jerusalem; the story of a casino built by the Palestinian Authority in Jericho; the history of gunpowder … the list goes on.

Every one of the 1,001 chapters — some are photographs; many are just one line; others continue for pages — connects to the one before it. Sometimes the connections are obvious and at other times, they’re only visible if you’re paying attention, like spiderwebs in sunlight. There’s a tremendous amount of research that has gone into Apeirogon, and when McCann is able to string together these different beads of information, stories and histories effectively, the novel is magnificent.

For example, Chapter 28 recalls the moments before Bassam’s daughter Abir was killed by a border guard (he shot her in the back of her head, with a rubber bullet). In the next chapter, we get a description of the rubber bullets that the Israeli Army uses (this should hit home, given the Indian Army’s use of pellets and rubber bullets in Kashmir) — the metal core of the bullet is tipped with special vulcanised rubber that bounces back to its original shape. Chapter 30 tells us that soldiers call these bullets “Lazarus pills” because they can be picked up and used again. Bassam’s daughter isn’t mentioned, but how can you forget that the 10-year-old didn’t get a chance to evade death the way Lazarus had? Chapter 31 is a description of a project by an artist who used hollowed-out rubber bullets as tiny bird feeders.

It doesn’t always work. You know Apeirogon wants to be an Important Book and that authorial ego makes some sections of the book feel preachy and laboured. Abulhawa’s point about how the Israeli state is depicted made me see how many chapters (including the ones about the case that Bassam filed, accusing the state of killing Abir) serve to make the coloniser seem vaguely honourable almost. But for most part, Apeirogon, despite its flaws, is beautiful.

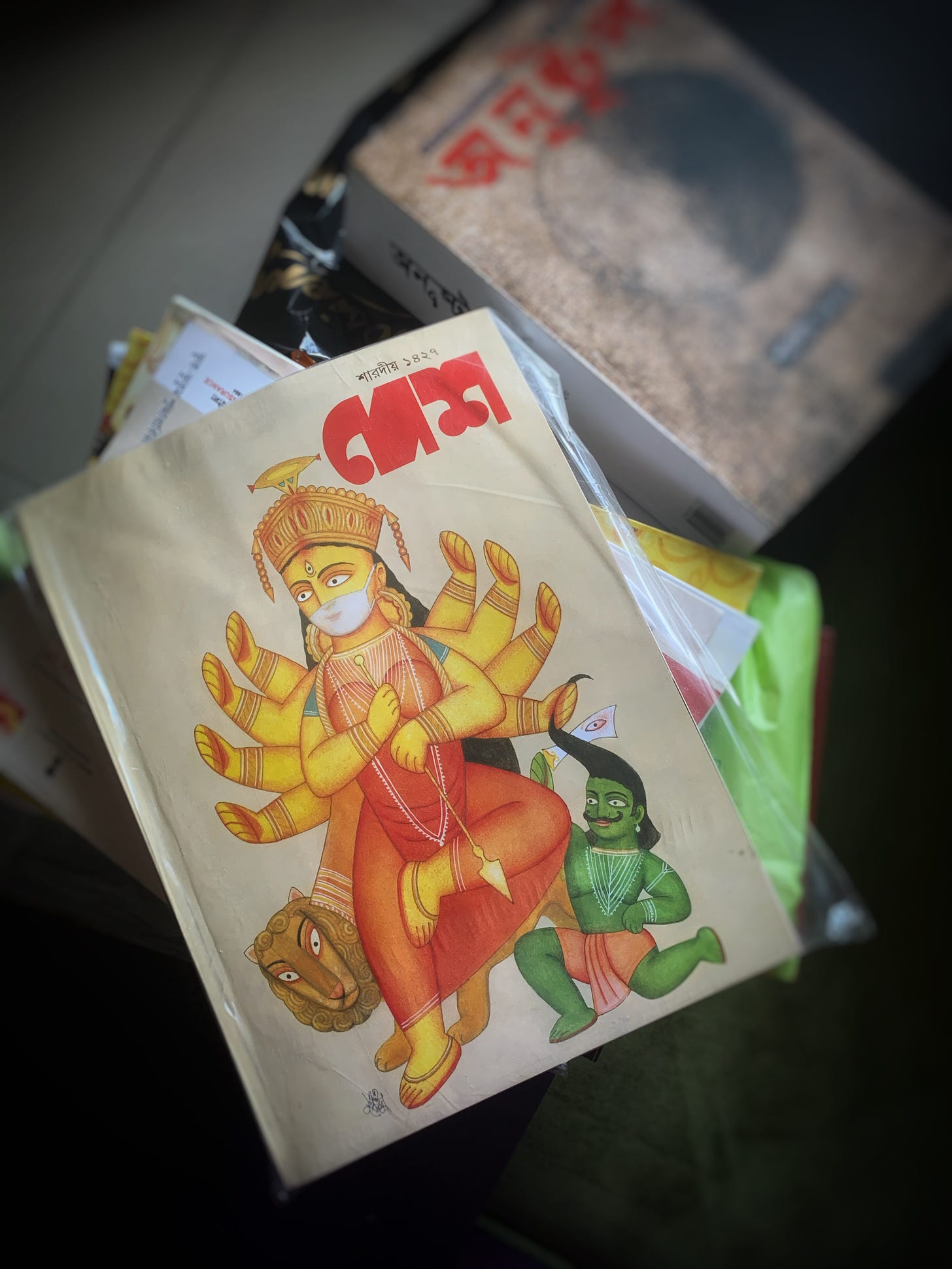

Before I sign off, let me point you to a wonderful series that Emergence magazine has done, titled Language Keepers about the struggle to revive and keep alive indigenous languages in California. Accompanying this series are a set of six podcasts. My favourite is this one, about the Wukchumni language. It felt particularly poignant because while I was listening to this podcast, my father was traipsing around Kolkata buying the Durga Puja specials of Bengali literary magazines. Magazines that he’ll have read from cover to cover by the time this week ends (and then grumble about); magazines that I’ll only photograph for their covers despite being entirely capable of reading them.

And with that, I will take your leave. Take care, stay safe and Dear Reader will be back soon.