Never Marry A Woman With Big Feet + Folk + Ursula le Guin

“…close up, a world’s all dirt and rocks. And day to day, life’s a hard job, you get tired, you lose the pattern. You need distance, interval. The way to see how beautiful earth is, is to see it from the moon. The way to see how beautiful life is, is from the vantage point of death.”

That’s from The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin. I’ve been re-reading fragments of her books and short stories since January 22, when we got the news that she'd passed away. It seems silly to say I’m heartbroken that an 88-year-old author, who lived a full life and has left behind shelves worth of wonderful writing, has died. Yet everything feels a little more hopeless when you know le Guin isn’t around to scavenge meaning, hope and beauty out of the contemporary. Her speech at the 2014 National Book Awards is famous, but you’ll find her incredible turns of phrase in almost every interview. Like this: “…that’s what translating is to me: you fall in love with somebody and so you want to possess them in your language.” Or this bit from the introduction she wrote for the 1976 edition of The Left Hand of Dispossessed:

In fact, while we read a novel, we are insane — bonkers. We believe in the existence of people who aren’t there, we hear their voices… Sanity returns (in most cases) when the book is closed.

Is it any wonder that no truly respectable society has ever trusted its artists?...

Apollo, the god of light, of reason, of proportion, harmony, number — Apollo blinds those who press too close in worship. Don’t look straight at the sun. Go into the dark bar for a bit and have a beer with Dionysios, every now and then.

One of the things I love about le Guin is that she seemed so conventional (so Apollo?) in her life choices — she studied literature, married and changed her name, worked as a secretary, raised children — while elegantly crafting disruptive, norm-shattering fiction. Her fierce imagination refashioned American landscapes into fantasy worlds that are described in riveting detail. She took ideas that we are taught to accept as basic and fundamental, and then melt them down to make stories that are great fun to read. Political? Sure, but it’s not as though she’s waving a flag of isms in your face. She’s telling you a story, one full of wisdom, wit, beauty and strength. You lose yourself in a le Guin novel or short story and it’s such a relief to know that these wormholes haven’t closed up all these decades after she first opened them up. Imagine a world where people are “ambisexual”, where one can be both mother and father. What is an anarchist utopia? What if your dreams changed the real world around you?

If you haven’t read any le Guin, here’s where what I’d recommend:

The Earthsea series

The Dispossessed

The Lathe of Heaven

The Left Hand of Darkness

If a six-part series seems too hardcore, then why not start with The Lathe of Heaven, which is about a guy who can change reality with his dreams? It’s a love story. With aliens and some radical ways to deal with overpopulation. No really. Read it.

Our Lady of Mad Good Words, thank you for the stories.

*

I finally finished Mineke Schipper’s Never Marry A Woman With Big Feet, which I confess I picked up largely because it had a Kalighat painting of a woman beating a man with a jharu on its cover. The book isn’t quite as witty as that image suggests and neither is it unputdownable as Wendy Doniger’s blurb promises, but if you have a little patience, it’s an interesting book. Schipper has been collecting proverbs from all over the world and she uses them to piece together how societies define and understand being female. She’s organised them on the basis of topic — proverbs about the female body, about being a widow or a mother or being pregnant, about power and so on. What this delivers very quickly is an acute understanding of how misogyny really is a worldwide phenomenon. It’s also fascinating to see how similar so many sayings are even though the societies that have birthed them are sometimes on different continents or separated by vast tracts of land/ water. It just goes to show we’ve been exchanging ideas long before the internet made it so damn easy to spread the word (literally).

With apologies to The Royal Tenenbaums, I problem a two-part problem with Never Marry A Woman With Big Feet. Number one: misogyny gets monotonous after a while. It doesn’t take too long to figure out that no matter what you do as a woman, if it isn’t housework then you shouldn’t be doing it. The chapter that focuses on the woman’s body in proverbs, for instance, feels so repetitive. This is partly because as women, most of us are familiar with the attitude of anxiety and criticism underlying the sayings and also because all the proverbs have one objective: to reduce a woman into a quivering mass of insecurity.

Also, Schipper doesn’t spend any time considering the differences between the societies she’s mentioning. This is because her point is that the one thing all these societies share is a deep-rooted male chauvinism. There’s no disagreeing with the fact that patriarchy has scored world domination, but the social status of women is vastly different between communities and countries. It seems short-sighted to only see the proverbs and not look at whether women have chosen to discard these blueprints or adapt them, or embrace them.

*

The highlight of this week’s reading has to be Zoe Gilbert’s Folk. This volume of 15 short stories are all set on fictional Neverness. Gilbert doesn’t bother with gentle introductions. She just lands you in the middle of this damp, wind-blown, gorse-pricked island. Here, the sinister is normal and the present is timeless. In her acknowledgements, Gilbert suggests the Isle of Man was the inspiration for Neverness. My suggestion would be to not look it up if you’re going to read Folk. It’s much, much more fun to let the island piece itself together in your imagination as you pick up details from Gilbert’s descriptions.

In Neverness, spirits fly out of the body to circle the skies with keening kites; boys are born with a wing instead of an arm; and the mist is something you can touch and in which you can swaddle a baby. But running parallel to all this is the hardship of reality — of death, pain, violence, dampness, cold and hunger. Folk feels vaguely like a shatter-pattern of a novel because the stories are all connected, with characters moving from the periphery of one story into the centre of another. By the end of the book, it feels like one of those medieval tapestries where so many stories are woven into one large frame. It’s also as creepy and weird as many of those tapestries, but in a very good way. Plus it has a beautifully illustrated, blood-spattered cover.

*

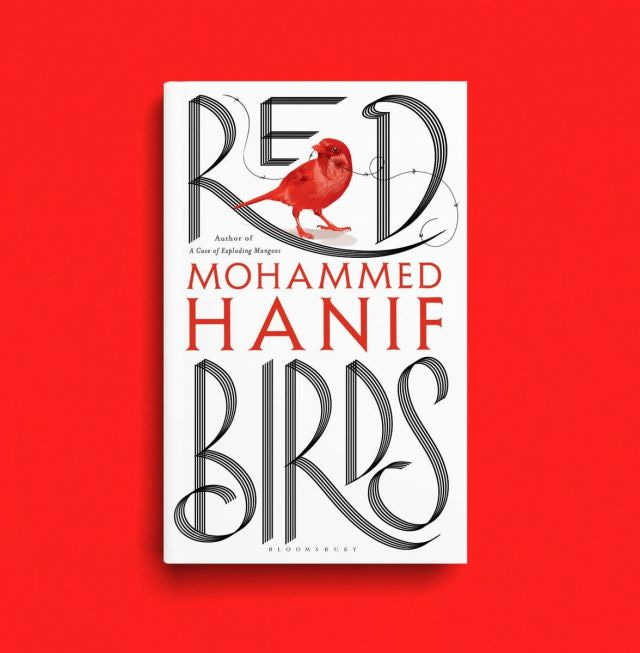

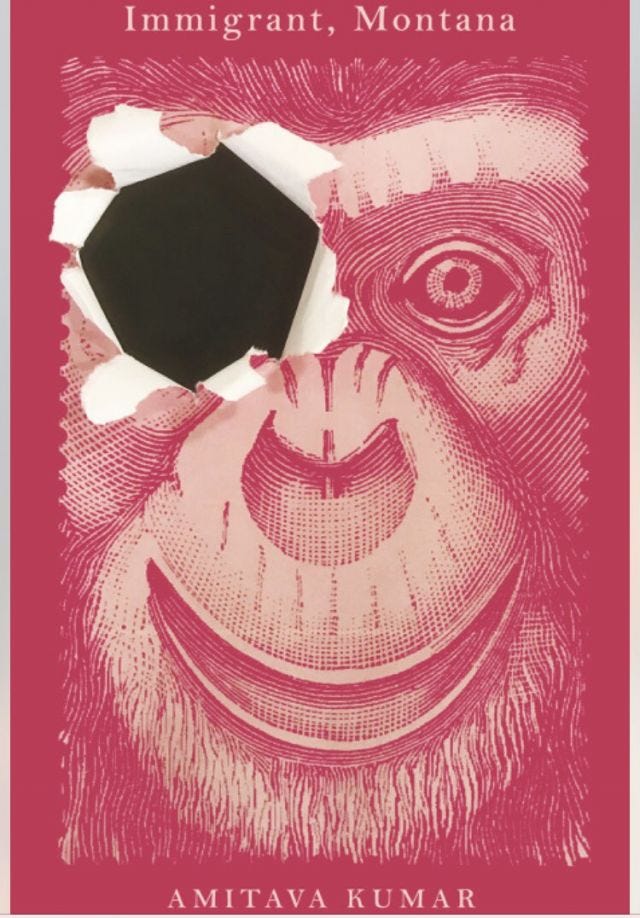

Speaking of book covers, these two caught my eye. Both of these books are expected later this year.

Rejoice!

*

Dear Reader will be back next week. Thank you for reading.