Latitudes + Jasmine Country + Enchantments + Rest and Relaxation

A couple of weeks ago, I heard a low, growling-sort of noise while I was reading. It sounded angry, feral. It was also coming from my person. Aliens bring out the Hulk, the moon brings out the werewolf and it turns out, purple prose unleashes the beast in me.

It’s not like I have anything against stylised writing. I just need the sentences to contribute to the plot or characterisation or world-building, rather than just preen prettily. When the lyricism of the writing just leaves me blinking bovinely and wondering what on earth happened to plot/ character, then it's time to low and behold. (I couldn't resist.) But before behaving like a cow, let me tell you about the novel that did restore whatever passes for balance in my person.

Otessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation has been on my to-read list for months now and my god, what a relief to read a book that deserves all the hyped praise it’s got. My Year of Rest and Relaxation is one of those rare good novels that can be summed up in one line: A young woman in her 20s decides the way to enter a state of drug-induced hibernation to deal with her grief and depression. Layered in this almost absurd (but oh-so-relatable) premise is life and art in pre-9/11 New York City, the way privilege works, and self-harm. There are some things that you can predict as a reader. For instance, if a book is set in pre-9/11 New York City, then somehow the roads in the novel will ultimately lead to the two planes hitting the North and South Towers of the World Trade Centre. This happens in My Year of Rest and Relaxation too, but the way Moshfegh uses the images from that tragedy that have become part of all our memories because of television news and the internet, is all sorts of unnerving.

Essentially, My Year of Rest and Relaxation is about an unnamed woman who effectively lobotomises herself using a terrifying cocktail of sleeping pills and sedatives. There’s no way to describe this novel without underscoring the paralysing sadness in which the narrator is smothered. Yet when you’re reading My Year of Rest and Relaxation, what strikes you isn’t the narrator’s misery, but her sense of humour. This woman is a crackling storyteller, a wordsmith who knows how to spark the imagination. There’s a withering and exhausted disapproval that she has for the world around her that makes the novel incredibly fun, even while it imprisons the narrator and you in whorls of misery. It's easy to start seeing the world through her perspective and lose sight of the fact that she's twisting all that is good, tender and kind out of shape. Her wit is her armour and underneath it is a creature of raw flesh and exposed nerves. As the novel progresses, the narrator's tone changes. The calmer it gets, the deader she is. You can see something inside her resists. A part of her finds inventive ways to resist sleep, but the one wake-up call that does register is rung by forces far beyond her control.

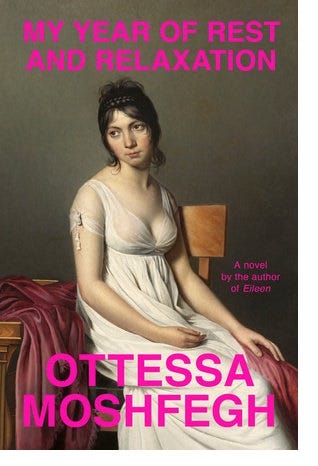

Even though the cover art is from the 18th century — it’s a portrait of a distinctly unamused woman; artist unknown, but the style suggests it’s by one of Jacques-Louis David’s students – My Year of Rest and Relaxation is steeped in contemporary art. The one job that we see the narrator (sort of) hold down is at an art gallery and her hibernation experiment culminates with her volunteering to becoming an artist’s muse. At one point, the narrator realises that there’s one particular drug that makes her sleepwalk, sleep-talk, sleep-socialise — basically, it brings her to life so that when she's sleeping, she's living and when she's awake, she's effectively sleepwalking. To put a stop to this, the narrator changes her locks and gives the keys to an artist she knows from her gallery days. He becomes her jailer, charged with making sure she has the basics she needs to survive while she pops her pills to stay unconscious for days on end. She also gives him the right to document her sleep and use it for his art. The artist is named Ping Xi (which happens to be similar to the name of a village in Taiwan that is famous for its lantern festival. Originally, the lanterns were released into the sky to signal villagers had survived bandit raids, but it’s now a new year ritual).

The art that comes of this collaboration is a great example of how good authors work out details without making a big fuss about it. We don’t know what Ping Xi knows of the narrator or why he decides to make the works that he does, and the art is a small part of the novel. But Moshfegh picks the perfect media and references when she describes it. Ping Xi makes a set of paintings and a video. He paints her in the style of 19th century Japanese woodblock prints, casting her in a modern floating world as it were. He also makes a video using footage of her sleep-talking into a camera that he’d set up in her flat, but the voice we hear is Ping Xi’s mother speaking in Cantonese. At one level, it’s exploitative of the narrator’s grief and misery — the fact that she’s signed a contract and given him permission to use her doesn’t make any of this feel less cannibalistic – but at another, it’s a little miracle. Because Ping Xi gets her.

The crisp, precise elegance of Moshfegh's writing in My Year of Rest and Relaxation came as such a relief because the three books I'd read before it ranged from vaguely dissatisfying to flat-out blah. The best of the three was Latitudes of Longing by Shubhangi Swarup, a volume of interconnected short stories that weave together environmental histories with the personal stories of characters. A minor character of one story becomes central in the next, and through their adventures transport the reader to tucked-away places in South Asia, like a remote village in the Himalayas, a haunted bungalow in the Andamans and a prison in Burma.

Swarup has a gift for description and as a result, every now and then there are fragments of exquisite, lyrical beauty in Latitudes of Longing. As a storyteller, though, she has a way to go. I started to read Latitudes of Longing last year and even though it has love stories, an innocent man being thrown in prison, well-behaved ghosts and other wonders, it was easy to set the book aside and not return to it. When I picked it up last month, every now and then I’d wonder why I was persisting with the book and find myself remembering how N.K. Jemsin writes about the earth and nature in her Broken Earth trilogy, particularly the first book which introduces us to the land in which her fantasy series is set. That world felt more real than the one Swarup writes about in Latitudes of Longing despite the latter being drawn from reality.

The first story in the volume is charming, but as Latitudes of Longing progresses, everything from the things people say to each other to the situations they find themselves in, feels increasingly artificial (even though they’re all entirely possible in reality). Curiously, the beauty of Swarup’s language became an obstruction. Those exquisite sentences glittered so brightly and were such a joy to re-read, but most of the time, they were also strangely disconnected from the characters and their stories. When the language in Latitudes of Longing was at its most beautiful, we're reading the perspective of the omniscient narrator, which made me feel distanced from the landscape and the story rather than immersed in it. It turned the familiar into the unfamiliar, an alien landscape that I could only hover over with the awkwardness of an astronaut, lumbering around in that bulky, immune suit.

That said, it’s only Swarup’s first book. Hopefully, she’ll find the balance between lyricism and plot as she goes along.

After finishing Latitudes of Longing, I picked up Queen of Jasmine Country by Sharanya Manivannan. Queen of Jasmine Country is an imagined biography of Andal, an ancient poet — 7th or 8th century — who stands out for being the only female among a group of Hindu poet saints known as Alvars. She wrote two collections of verses in praise of Vishnu. The first one, Thiruppavai, urges people to pray to the lord. The second, Nachiyar Thirumozhi, is richly erotic and one of them is part of the traditional Tamil wedding ceremony (I think). Legend has it that when she merged into Vishnu when she was just about 16. If you’re from North India, then she is reminiscent of Meera, another saint who wrote songs in praise of Vishnu. Both these women worship the lord through their romantic, erotic love for him.

I know next to nothing of Andal and her poetry and it was this excerpt from Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess by Priya Sarukkai Chabria and Ravi Shankar, titled, “Why a single poem by Andal needs four different translations”, that got me interested. It’s easy to see why Andal would fascinate a writer, particularly one with feminist leanings. A foundling who finds not just a home, but a father who will teach her to read and write is the stuff of magic. Add to that the story of how Vishnu appeared in her father’s dream and said he would only wear the garland that has first been worn by Andal, who was originally named Kodhai (which means garland. Andal means “she who ruled”). And then, at 16, she’s gone, leaving behind poems that both scandalise and amaze.

Unfortunately, Manivannan chooses to break down whatever little is known of Andal’s life into poetic fragments and the net result is that the novella makes sense only if you already know the legends and stories. If you pick up Queen of Jasmine Country only because it has an evocative title and a pretty, purple cover, you’ll find yourself dunked in word soup. Manivannan's attention is trained upon depicting Andal and her desire in poetic terms. Everything else, including plot, is forgotten. Maybe now that I have ended up doing a little bit of reading on Andal, the book would feel more rewarding, but I have to admit, I'm not even slightly motivated to give this book another shot.

Knowing the story didn’t help with The Forest of Enchantments, in which Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni retells the Ramayana from Sita’s perspective. One of Divakaruni’s most popular books is The Palace of Illusions, in which she presents the Mahabharata from Draupadi’s point of view. In this new book — which has a beautiful miniature painting as a cover – Sita writes her version of the tale after Valmiki shows her his Ramayana. Divakaruni’s Sita seeks to remind the reader that the Ramayana isn’t just about male ego, masculine chest-beating and war. At its heart is the love story of Rama and Sita, and every leading male character in the story has a wife who has been largely forgotten. Except Surpanakha, who stands out in every retelling for her independence, and in The Forest of Enchantments, she is the chief villain instead of Ravan.

This is not a novel intervention from Divakaruni. The idea of privileging Sita and other women is an old one –Valmiki himself did it in the Adbhuta Ramayana (yes, he is said to have written the alternative version of his own original) and by many others since, including Chandravati in the 16th century and Volga in the 20th century (if you haven’t read The Liberation of Sita, you must). The idea of a sisterhood that Divakaruni tries for in The Forest of Enchantment is powerfully realised in Volga’s retelling of the Ramayana.

Of course, the fact that it isn’t new is no reason to not write something, but it does beg the question of what is being added. The Forest of Enchantments offers little by way of insight. The idea that Rama did love Sita – despite the middle and end to that bad romance – is not a revelation; it’s the central premise of the epic in every version that I can recall. The idea that Rama ordering Sita to undergo trials by fire and banishing her when she was pregnant, was him overcompensating for his father’s ‘weakness’ (specifically, being manipulated by his wife, Kaikeyi) is also a standard explanation. Surpanakha’s dogged pursuit of Sita — essentially stalking her from Lanka to Ayodhya after the war – is the only bit that is intriguing because Surpanakha has been criminally overlooked by most Ramayana tellers. Divakaruni doesn’t ignore the mutilated rakshasa princess, but neither does she give her the space and attention that could have made this book special.

It’s also interesting to note what Divakaruni does include in The Forest of Enchantments. For instance, she chooses to include the story from Adbhuta Ramayana that says Sita was Mandodari and Ravana’s daughter (learn Game of Thrones, learn), but she doesn’t keep the climax in which Sita saves the day in the battlefield. Divakaruni’s Sita can fight, but she’s more a mixed martial arts practitioner than a warrior. That glory is reserved for Rama. Neither does Divakaruni include the bit in which the gods appear and rap Rama’s knuckles for making Sita undergo the trial by fire. Instead, she tells us he was crazed with grief at having lost her to the flames. Ultimately, Divakaruni’s Sita is the conventional good wife, making sure Rama doesn’t look all bad in his worst moments. Did we really need yet another retelling of the Ramayana to tell us this?

The most frustrating part of The Forest of Enchantments though is Divakaruni's writing style. It’s so casual and flat that it makes Sita seem simplistic. Divakaruni conscious chose to use language that sounds contemporary, but because she doesn't modernise or update anything else, it just sounded like someone trying to sound young. The palaces, the customs, the prophetic dreams, the weapons, the magic – all the epic elements are in place, but the soundtrack is 20th-century. The point is not that modern colloquialism can't be literary, but that it has to be used in a way that adds depth to the story and characters, rather than making them simplistic. To add a layer of modernity that barely subverts or disrupts any of the traditional setups of the epic is bizarre and boring.

*

And with that I'm going to go and re-read the Broken Earth trilogy because after this last set of books, I really feel the need for some good fantasy fiction. In the meanwhile, here are a few links to articles that stayed with me.

"I explained to Hoda that I do not see Behrouz Boochani in this image. When I look at this image over and over again, I do not see myself. Instead, I see a human being who is standing behind the borders, a human being standing in the space between human and animal. He is not a human being because he has been expelled from human society, and he is also not an animal. He is precisely on the threshold of law and violation of law; he has been positioned on the threshold of civilisation and barbarism. This is significant – both Hoda and the spectator view the image from this perspective, they see this as the portrait of Behrouz Boochani, but I see it from quite a different perspective and see different aspects."

By Behrouz Boochani left Iran seeking asylum in Australia, but for the last six years, he's been in an offshore detention centre on Manus Island. On January 31, Boochani won Australia's richest literary prize for his book, No Friend but the Mountains.

A brief history of crime and mystery in the world's Chinatowns.

Finally, a treasure from James Baldwin. I started looking up his stuff because I saw the film If Beale Street Could Talk a couple of weeks ago (it's a great adaptation of Baldwin's novel to film, and totally heartbreaking) and came across the masterful essay, "If Black English isn't a language, then tell, what is?"

Beat to his socks, which was once the black's most total and despairing image of poverty, was transformed into a thing called the Beat Generation, which phenomenon was, largely, composed of uptight, middle-class white people, imitating poverty, trying to get down, to get with it, doing their thing, doing their despairing best to be funky, which we, the blacks, never dreamed of doing--we were funky, baby, like funk was going out of style.

Now, no one can eat his cake, and have it, too, and it is late in the day to attempt to penalize black people for having created a language that permits the nation its only glimpse of reality, a language without which the nation would be even more whipped than it is.

*

Thank you for reading and Dear Reader will be back soon.