Lady Trent, Turned On, The Orchid Thief & more

Of dragons, sex robots from ancient Greece, orchids and heart advice

Dear Reader,

Now that I have finished all five volumes of the memoirs of Lady Isabella Trent and her granddaughter Audrey, I am heartbroken. Not only because there are no more books to read in this wonderful series by Marie Brennan, but also because no ex of mine has had the good sense to call me, “my artistic, keen-eyed love, my angel of the pencil”. No wonder none of those relationships lasted.

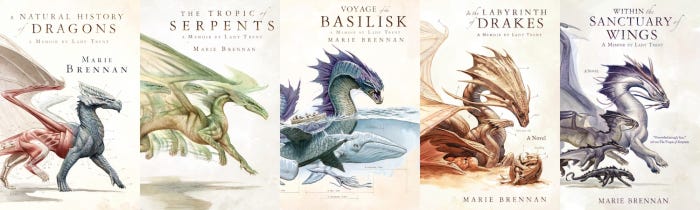

I’d been eyeing the Lady Trent books (mostly because of the gorgeous cover art by Todd Lockwood) from the moment they showed up at Trilogy, my favourite bookshop in the city, but it wasn’t until March that I actually bought the set. Days after I brought the books home, the lockdown was announced. I cannot even begin to tell you how thankful I am that I got the books before non-essential services had to shut down because the Lady Trent books have felt like a lifeline in these bizarre, broken times.

I’m among those who are lucky enough to not be seriously impacted by Covid-19 — I have a home, food, internet, my health and a job (for now at least). While some people I know have tested positive for the virus, none of them has the serious variant of the infection. If you thought all these silver linings means I’m full of gratitude and good cheer, think again.

I’m a gold-standard grump even when I don’t have to do household chores or see a stream of sourdough photos on Instagram. With these petty irritations, I’m … thankful that I live alone because otherwise, by now I’d have been booked for murder. In addition to this essential grouchiness, there’s the nerve-fraying sadness of Covid-19 as it exposes the terrible failures of our social and political systems. Here in India, the government has proved itself to be woefully incapable of offering relief to the most vulnerable in our society and the private sector is adding new dimensions to capitalist greed, with ambulances and hospitals inflating their costs to monstrous levels (Rs. 24,000 for ambulance rides; Rs 100,000 per day as hospital charges; this in a country where just 3% of the workforce earns more than Rs 50,000 a month and 45% earns under Rs 10,000. We don’t have numbers of how many have lost their livelihood during this lockdown).

For those of us who aren’t directly impacted by the infection, the lockdown has given us opportunities to introspect, appreciate beauty and cherish what we have. But these are wretched times, when gratitude comes with guilt because what we feel grateful for are invariably simple things that should not be markers of privilege and yet are exactly that. While one slice of the population deals with its anxieties by compulsively doing live streams on social media and video calls, there are thousands who cannot afford to call home. Some of us distract ourselves with complicated recipes and beautiful plates of food while others make meals of cheap biscuits and eating once in two days. There are those being plunged into depression because they’re isolated and housebound while others walk along highways and train tracks, in the blazing heat of summer, in the hope of finding shelter and their way home.

With all this festering in my head, it’s been hard to focus on anything. I can’t seem to read beyond a few paragraphs before zoning out and it’s been stupidly easy to abandon books. Like, for instance, The Orchid Thief by Susan Orlean, which is about orchids, the obsession these flowers inspire, and a guy named John Laroche who was arrested for poaching rare orchids. Orlean is a fantastic writer who describes places and people beautifully. The book is frequently hilarious and packed with information that makes orchids and Florida seem magical.

I finally gave up on it about two hours before sitting down to write this newsletter.

Orlean has written for The New Yorker. Charlie Kaufman adapted The Orchid Thief into the film Adaptation. (Adaptation has one of the best stream-of-consciousness monologues about writing ever.) I feel like an idiot for not being able to dredge up any enthusiasm to finish the book and I can’t really tell whether what is meandering is Orlean’s writing or my attention.

It took me about a month to read 150 pages and when I reached page 154, I found myself wondering what was the point of The Orchid Thief. Was I supposed to be awed by Orlean’s language? That mission was accomplished within the first 10 pages. The book is 348 pages long. Wherefore? I have since managed another 50 pages, which were not unpleasant, but neither were they compelling. The Orchid Thief has felt like a collection of tangents — fascinating tangents, but still tangents — that are supposed to distract me from noticing that Orlean didn’t need 348 pages to tell Laroche’s story.

Or maybe she does. If I finish the book and change my mind, I’ll let you know.

I also struggled with Turned On: Science, Sex and Robots by Kate Devlin, which goes to show that my brain is definitely at least a little broken because what kind of a person loses interest in a book about sex robots? (Me. That’s who.)

That said, even if your brain is doing its best impression of a drunk slug, the first chapter of Turned On is a gem. It’s a historical perspective on sex robots. Did you know that the world of mythology — specifically, Greek and Roman — has its share of cyborgs and sex robots? Well, it does. Allow me to introduce you to Laodamia whose husband was the first to die in the Trojan war. The grieving Laodamia got a bronze likeness of her husband made and was seen “interacting” with said likeness by a servant who assumed there was a living man in Laodamia’s bed. That, ladies and gents, is the first written tale of a sex robot according to Devlin. And guess what? It’s possible that the dildo was invented 25,000 years before the wheel. Also, agalmatophilia —sexual attraction to a statue, doll or mannequin — is a real word. Scrabble players, you’re welcome.

My Kindle informs me that I have read 95% Devlin’s book — which, incidentally, means I also read through at least half of her bibliography. Why? — but I have only the blurriest of recollection of the later chapters. From what I remember Devlin is at her best when she’s exploring how we understand intimacy, rather than the tech sections. Sex technology is not driven by perversion, but by a very human desire for companionship. How it develops will depend to some extent on how societies adapt to changing notions of relationships, ageing and sexuality. Devlin talks about how robots could care for people with tenderness but without emotional bias and how deeply people get attached to inanimate objects, like digital assistants and bomb-recovery robots. It’s oddly heartening to know that for all our terrible flaws, humans as a species are capable of loving so deeply and generously.

Into this morass of abandoned books came my saviour: Lady Trent, a lover and a fighter, and a dragon researcher.

The memoirs of Lady Trent.

I tore through these books, reading them with a sense of joy that I had almost forgotten because of this blasted lockdown. Thank heavens I didn’t come across A Natural History of Dragons when it first came out in 2013, because then I would have had to wait for Brennan to finish writing the following books. Now, I had to exercise no such restraint.

One of the things that makes the first three books so easy to read is that the chapters are short, which gives the reader a sense of moving quite swiftly through the book. The plots themselves move slowly, reflecting how scientific research is a slow business. Brennan is also a master world-builder. No indulgent descriptions, no elaborate histories; just the details you need and a clever balance between familiar and fictional. The most pronounced departure from what we understand as reality is that in this world, dragons are real. Also, in their history, there was once a draconean civilisation made up of beings who were bipeds (like us) but with dragon heads and wings.

In terms of structure, Brennan turns conventions on their head and packs the bulk of the action in the final chapters. For much of the book, nothing seems to happen, but you don’t mind because you’re seeing a new place through Lady Trent’s eyes. This works beautifully.

Each volume of Lady Trent’s memoirs is set in a different part of this world, which Lady Trent explored while researching dragons and draconean behaviour. Like books from the Victorian era, the volumes have illustrations, drawn by Lady Trent in fiction and Todd Lockwood in reality. A Natural History of Dragons is set in mountainous Europe. The Tropic of Serpents travels through a variation of central Africa. The Voyage of the Basilisk goes to islands that I think were inspired by Polynesia. In the Labyrinth of Drakes is set in a region modelled on Arabia. Within the Sanctuary of Wings goes back to the mountains, but this time Lady Trent and gang go to a Himalayas-inspired landscape. Don’t read them out of order because there’s a very neat arc that Brennan is plotting through these books.

The last book — Turning Darkness into Light — has Lady Trent’s granddaughter Audrey as its protagonist. Audrey is a rising star of linguistics despite the prejudice she faces as being a woman and that too of colour (her mother is black). When she’s commissioned to translate what seems to be a key relic of the ancient draconean civilisation, the bookish task of translation proves to be a thrilling adventure. It’s good but I didn’t love this last book as much as Lady Trent’s memoirs. There’s also a short story on Brennan’s website, but it only makes sense if you’ve read Audrey’s adventures.

Lady Trent is feisty and funny and in the books, the act of writing her memoirs for an audience also means she’s talking to her reader, which makes it feel like making friends with someone. Brennan describes Lady Trent as “more real” than any other character she’s written. Lady Trent should seem impossibly perfect with all her personal and professional accomplishments, but throughout the books, she is both brilliant and very flawed. She’s also a lunatic, which makes for excellent stories. Plus, she has a wonderful set of friends and colleagues (who could totally have their own series. Tom versus poncy philosophers! Natalie going up against the male-dominated world of engineers!). What’s not to love?

My favourites in the series are The Tropic of Serpents and The Voyage of the Basilisk. Within the Sanctuary of Wings was the only one that I didn’t find wildly compelling (it’s fine. Just a bit ridiculous and melodramatic in parts, so not as good as the others). I’m quite certain Lady Trent’s memoirs are books that I will want to re-read to escape the world around me.

Speaking of re-reads, a recent conversation with a friend reminded me of a book that I think may offer some comfort in these godawful times. When Things Fall Apart by Tibetan Buddhist nun and teacher Pema Chodron is one of the most beautiful little volumes you could read right now. While the book is about Buddhist concepts and philosophy, you don’t have to be religious or even interested in religion to appreciate the ideas Chodron is exploring. They’re rooted in basic and relatable human feelings and experiences — fear, helplessness, hopelessness, despair, grief. Here’s a bit that I’ve found myself remembering the last few nights, when I shut the computer down after finishing work.

“In Tibetan there’s an interesting word: ye tang che. The ye part means ‘totally, completely,’ and the rest of it means ‘exhausted.’ Altogether, ye tang che means ‘totally tired out.’ We might say ‘totally fed up.’ It describes an experience of complete hopelessness, of completely giving up hope. This is an important point. This is the beginning of the beginning. Without giving up hope — that there’s somewhere better to be, that there’s someone better to be — we will never relax with where we are or who we are.”

Brain Pickings has a number of quotes from When Things Fall Apart here. Pick up the book and flip through its pages when you’re feeling troubled. At worst, you’ll roll your eyes and abandon it. At best, you’ll feel enriched and feel the hammering of your pulse slow down.

Take care, stay well and Dear Reader will be back soon.