The other day, I found Rs. 10 in my pocket. It was a complete surprise and even though Rs. 10 is not exactly a princely amount (according to today’s exchange rate, that’s 11 cents if you’re in America or Europe), the tenner made me inordinately happy. Obviously, this has nothing to do with the note’s actual value. At best, it will pay for parking at Kolkata’s Lake Market, but that’s not really the point. The Rs. 10 popped up out of nowhere. A bit of whimsy from a universe groaning under the weight of awfulness? I’ll take it gladly. These are times in which the little joys are precious. I’m hoping this newsletter showing up in your inbox unexpectedly will feel much the same way — it’s a little something that has very little value in the larger scheme of things, but hey, it’s here!

Today, I come to you with not books, but a film I saw in an art gallery. Some of you might know that I have a column in the Hindustan Times in which I write about films and shows that have left me with Thoughts. Since it comes out in the print edition of the newspaper, there’s a non-negotiable word count I have to stick to, which has been quite a re-education after all these years of writing for websites. Being a columnist with a print publication is a bit like making your peace with Mumbai real estate — you squeeze in as much as you can into spaces that feel cramped but which you’re grateful to have. Sometimes, the word count is not a bad thing because it forces you to focus and not waffle; but sometimes, it makes you (read: me) whinge like tantrummy toddler. This is one of those weeks. So I thought that I’d show up here with the unedited version of my column on Pallavi Paul’s How Love Moves.

Paul’s film felt special when I watched it a couple of weeks ago. It feels all the more so now, as an online backlash unfolds against Mohanlal’s L2-Empuraan because it has a sequence that seems to reference the 2002 Gujarat pogrom. The latest news is that L2-Empuraan will make 17 cuts to appease the trolls — this is after receiving a CBFC certificate, mind you. Anyway, my edited column is here and the unedited one is below. Thank you for reading and Dear Reader will be back soon.

In the far corner of the gallery Project 88, there hangs a velvet curtain with the Urdu word dum (breath) written on it in gold thread. A few steps away lies a white body bag, embroidered with colourful peacocks. In the belly of the gallery is a large screen. When it lights up to play artist Pallavi Paul’s film How Love Moves, the screen becomes a portal that takes the viewer to Delhi Gate Cemetery.

It’s a place with the air of a secret garden, with its overflowing green and majestic peacocks. Here, lives are connected by death and life is treasured. A gravedigger says he doesn’t believe in death. The living don’t die, he maintains. They just make their way past the veil that is life to the afterlife, to the divine. In How Love Moves, the graveyard is a place of hope, where those who have lost someone see glimpses of their beloved in a butterfly, feel their presence on a breeze. It offers refuge to the homeless and those in need shelter. We’re told stories of how there have been times when the living have lain next to the death and it became impossible to tell one from the other. The dead are buried in this graveyard, but they are not forgotten. If anything, they are resurrected through the act of remembering.

Two narrators share their stories with us over the course of 63 minutes. One is a migrant woman who came to India in search of a new life and along the way found love, only to end up witnessing her husband’s brutal murder during the Delhi riots of 2020. The other is a chatty gravedigger named Shamim Khan, who, with his equally chatty colleagues, buried approximately 4,000 bodies in the months when the second wave of Covid-19 and riots ravaged the capital. These two voices keep alive the memory of people who have been anonymised into inadequate data points by death and trauma. “Those who understand death know the dead are not worthless,” Shamim says at one point, adding, “They’re Allah ki amanat (God’s creations) and must be returned to him with respect.”

Paul is a gifted interviewer whose subjects seem to be aware of the camera, but not performing for it. There are hauntingly beautiful moments shot by cinematographer Ashok Meena, which offer an intimate and unclichéd portrait of Delhi as a city of mist, shadow, peacocks and earth tones. (I’m not absolutely certain, but I think Meena was the cinematographer on Against the Tide, which is an exquisitely-shot documentary about Mumbai’s fisherfolk.) Meena’s cinematic gaze highlights the grace in the people and places it records, rather than the scars. The film makes space for ugliness too, through Paul’s use of viral mobile clips that were circulated during the lockdown as well as snippets from news channels.

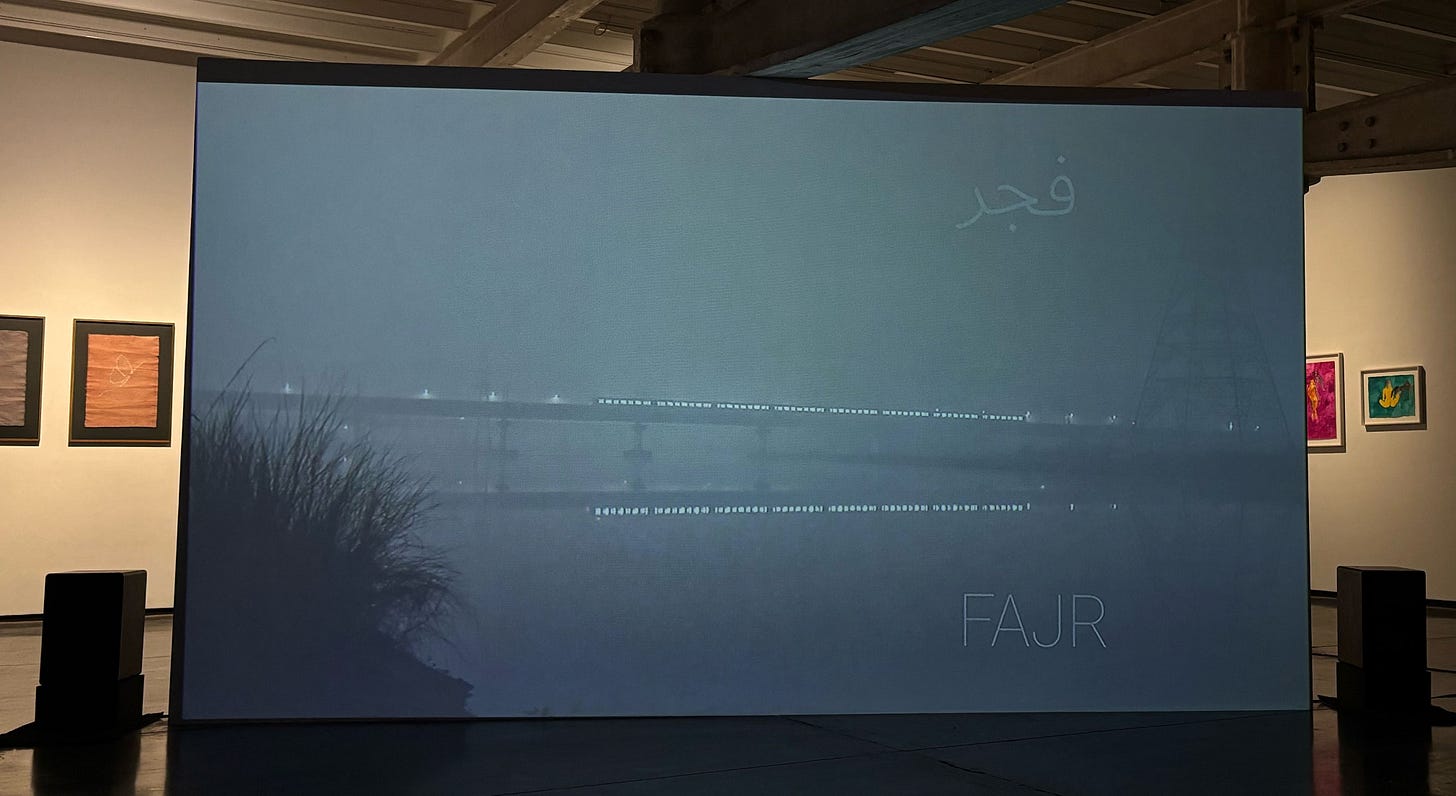

The storytelling is sophisticated, made both more beautiful and sharp by superb editing. The 63-minute film is divided into five parts, each named after Islamic prayer times (fajr, zuhr, asr, maghrib, isha), and to watch How Love Moves during Ramzan feels like the very definition of timely.

How Love Moves is a powerful film about our recent past and it is all the more impactful because as a society, we seem to be intent upon putting the pandemic years behind us. Our almost frenzied need to forget those troubled and troubling times runs counter to what Paul has done — remember and feel for that past. If you’re in Mumbai, I cannot urge you enough to brave the dug up streets and unforgiving traffic to see How Love Moves. Since it is part of Paul’s solo exhibition, the film is freely available to anyone who can journey to the far end of south Mumbai.

Being in an art gallery in Colaba technically makes How Love Moves more accessible than most documentaries in India, but in practical terms, its location makes the film weirdly unapproachable as well (especially if you’re coming from one of Mumbai’s far-flung suburbs). A gallery is not considered the natural habitat for a documentary film, but it remains one of the few spaces where being mainstream and formulaic is not an advantage. Here, there is room for dissent, experimentation and grace. There is also the hope of finding one’s audience. Paul’s film could easily have been labelled a documentary, but that would have meant joining the league of brilliant Indian documentaries that the public can’t access without help from piracy.

Perhaps Paul will make a conventional documentary feature with the footage she has collected, but as the Indian film industry tells us repeatedly, making the full-length feature film you want is a labour that even Hercules would have balked at if he knew everything he’d be up against. There are obstacles at every level and each one can twist a film to become less creative, less brave, less relevant, less beautiful. It takes a miracle for a film to go from being greenlit to released, but in the age of “anticipatory compliance” and fear, even a miracle may not be enough to ensure you make the film you dreamt of making.

Last week, filmmaker Anurag Kashyap pointed to precisely this problem during a venting session in the comments section of his own Instagram page, after binge-watching the masterpiece that is Adolescence, created by Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham. Incidentally, if you’re feeling a post-Adolescence emptiness, find Avinash Arun and Ishani Banerjee’s School of Lies, which is one of the most poignant portraits of boyhood that we’ve had in Indian entertainment. Then watch Shuchi Talati’s Girls Will Be Girls, which won the prestigious Independent Spirit John Cassavetes award last month. Especially considering how mainstream entertainment dumbs down teenagers on screen, it feels like a blessing that regular streaming platforms made space for School of Lies and Girls Will Be Girls.

It isn’t surprising that Kashyap was triggered by Netflix’s CEO Ted Sarandos taking credit for his platform backing inventive storytellers. The coffee shops of Bandra and Versova are haunted by lingering echoes of disgruntled writers, directors and technicians who blame interfering producers for mangling their work out of shape. (Netflix in India is known for being particularly interfering.) “How do we ever create something so powerful and honest with a bunch of most dishonest and morally corrupt @netflix.in backed so strongly by the boss in LA (sic),” Kashyap wrote on Instagram, voicing the frustrations of many. There must have been a Mexican wave of agreement that spread across Andheri, Juhu and Bandra when Kashyap’s post popped up on Instagram.

Yet against all odds — and there are many — somehow, there are storytellers who manage to create work that is impactful, courageous and beautiful. Sometimes, you have to look for them in art galleries.

How Love Moves is on at Project 88 till April 26. The film is screened three times a day. Please check the gallery’s social media or call them to confirm timings.

Thank you for sharing, Deepanjana. Beautiful. Looking forward to see How Love Moves.

Hello. So lovely to see my Delhi people here. Makes it a little more cozy somehow. How are you? Speaking of films did you ever go see Shameless? I helped co write it about ten years ago but at this point never thought. It would see the light of day…I’m so curious what the Indians made of it. I’m told it was well received.