Dear Reader,

Before anything else, can I just say I’m seriously impressed by the speed at which the books in the giveaway pile got claimed? I didn’t check my email until a few hours after sending out the last newsletter, but in real time, it seems most of the books were claimed within 10 minutes of the newsletter landing in inboxes. That’s mad. I’ve also sent so many “Sorry, that book’s already been claimed” messages and believe me, it really does break my heart to write those. I hope the books you were eyeing find their way to you soon.

Here are the titles that haven’t been snapped up (just in case):

Legacy of Nothing

The Monsters Still Lurk

Mee and Juhibaby

Dust Under Her Feet

Bhumika

Cut

No Margin For Error.

So that’s that, as far as the giveaway is concerned.

On to five books that have nothing in common beyond acting as ladders to climb out of the pit of despair that is Indian current affairs. (Speaking of which, for those interested, Dexter Filkins’s essay on the current political establishment’s attempts to contort India into a Hindu rashtra is here. Highly recommended even if it is depressing as all hell for those of us who are not RSS loyalists.)

I had great fun zipping through Jasper Fforde’s The Fourth Bear. Set in the fantastical county of Berkshire in England, this novel has a lot of violence, some smuggled porridge and answer to the critical question of whether a gingerbread man is a biscuit or a cake.

Berkshire police has a Nursery Crimes Division since this is one part of the UK where Persons of Dubious Reality (PDRs) seem to live happily ever after. DCI Jack Spratt and DS Mary Mary run this division, which handles all complaints concerning nursery rhyme characters and other PDRs.

When a journalist nicknamed Goldilocks disappears after running out of a house inhabited by three bears and a psychotically violent Gingerbread Man escapes from the asylum, it’s up to Nursery Crimes Division to save the day. Which of course they do. They also figure out the cake or biscuit question and provide an excellent explanation for why only Baby Bear’s porridge is the correct temperature for Goldilocks.

The best thing about a Fforde novel is that it’s rich with references from a variety of literary genres. The Fourth Bear, for instance, has everything from Shakespeare and Prometheus to aliens and Punch and Judy in it. The other thing that Fforde novel is guaranteed to be is bonkers. So much fun. Please read.

And if you haven’t read his thoroughly lovesome Thursday Next series, you really must. Start with The Eyre Affair. It’s a book I’ve re-read almost as many times as my Enid Blytons.

The cover of The Peace Machine by Ozgur Mumcu promised me “a rollicking Ottoman steampunk adventure”. Sold, I thought. To me, the idea of adding steampunk to the richly-historic Turkey sounded electric. One hundred pages into the book, I had only one question:

(translation: What the hell is going on?)

It’s not as though The Peace Machine is without merits. There are some beautiful descriptions that pop up unexpectedly and eventually, the book presents you with one serious pickle of a question. If losing free will could guarantee the absence of hatred and ensure peace on earth, would it be worth it? (A question that is particularly relevant to contemporary India if you are an RSS or BJP supporter.) The problem is that to reach the point of the book, you have to wade through an awkward, jumpy narrative that feels ridiculous and laboured.

Mumcu’s novel offers an alternative history of the early 20th century and clearly wants to be the wordy equivalent of raising a single eyebrow at historical revisionism (we’ve got a version of this happening in India too). I just wish whoever edited Mumcu’s narrative had raised that eyebrow at Mumcu instead. Because the tricksy language of The Peace Machine and the abrupt shifts in the story do nothing to either engage a reader or communicate with them. You sense there’s a meaning hidden in the flamboyant writing, but you can’t quite pinpoint what the hell that meaning is. I’m sure The Peace Machine feels less obtuse to those well-versed with Turkish history and current affairs. As far as I was concerned, the book’s saving grace is that it’s just 200-odd pages.

Aranyaka: Book of the Forest, a graphic novel by Amruta Patil, written in collaboration with author and mythologist Devdutt Pattanaik, declares itself to be a “book of the forest”. Yet this is very much a story of humans. In fact, for me, the sections deliberating on nature were the least memorable parts of the book. Ironically, the forest in the book of the forest feels more like a backdrop than an animate character, and despite the stern warnings delivered by narrator and heroine Katyayani about not romanticising the wild, the book seems to do exactly that a lot of the time (especially in the later chapters).

In the source myth, Katyayani is the silent wife of the wise Yajnavalkya, a sage who (unwittingly) shone a spotlight on two women philosophers, Gargi and Maitreyi. Maitreyi was Yajnavalkya’s second wife and among the few who has an Upanishad with their name. She’s the scholar’s equal while Katyayani, the first wife, keeps the home fire burning (and gives birth to four sons). At the end of the story, it’s almost as though there’s a separation of the man and his intellect. Maitreyi gets the intellect and Katyayani gets the man. To even attempt that separation feels unnatural to me and is vaguely reminiscent of the experiments to separate daemons from their humans in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy (which has now been adapted into a television/web series).

But Yajnavalkya, transformed into “Y”, is not the focus of Patil and Pattanaik’s attention in Aranyaka. Katyayani is and to this end, she gets a makeover and a voice. Through her perspective, Patil tells the story of a couple who meet in the wild and then slowly but steadily, civilise themselves. They build first a relationship, then a home, then a family and finally a community, distancing themselves from the wild with every step.

This Katyayani is as large as life, and the way she embodies the stereotype of conventional femininity – she’s the homemaker – is refashioned as rebellion. Her hunger is transgressive because it implies she is aware of her own desires and defiantly privileges herself as an individual over the collective. She seeks not just sustenance but also pleasure. There’s an interesting exploration of everyday sexism and gender roles carried out in Aranyaka through Katyayini and her husband Y’s characters.

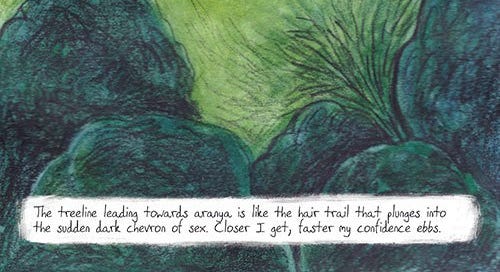

Though it’s a graphic novel, the allure of Aranyaka is in its words rather than the illustrations. Patil’s art often has a deliberate air of childish simplicity to it, which I struggled with occasionally. Largely because of the Storyweaver books, I see some incredibly inventive illustrations and the art in Aranyaka didn’t feel reflective of the riches it’s drawing upon.

(A page from Aranyaka, by Amruta Patil and Devdutt Pattanaik)

The language of the book, on the other hand, is layered and lovingly wrought. If you’ve read Patil’s previous books inspired by the Mahabharata – Adi Parva: Churning of the Ocean, which I loved, and Sauptik: Blood and Flowers – then you’ll recognise Patil’s storytelling style. Different strands of stories and histories are woven into her retellings, adding textures, highlights and accents. If you’re expecting a conventional narrative, it can feel abrupt because while there’s a lot she adds to her stories, there’s also a lot from the source myths that Patil discards in her retelling. I’m very fond of how she weaves these tapestries because I find myself mulling over the ideas contained in them for days afterwards.

One of the things I love about Patil’s Katyayani is how unabashed she is about her body. It’s a joy to see a large woman whose body is accepted as natural by herself and eventually by those around her. There’s no fetishising it and neither is her body flaunted performatively (I’m thinking of the bulk of the body confidence posts on Instagram, which, for all their good intentions, are very theatrical). Katyayani the Large just is. I also loved how Patil showed the friendships between the women in this book. Aranyaka very consciously turns its back to the idea that women will end up in a catfight just because there’s a man in the picture. Instead, Katyayani, Gargi and Maitreyi get past the rough edges of their insecurities and jealousy to become friends. They truly see each other and perhaps one of the most touching moments in Aranyaka is when Gargi makes a gift for Katyayani that is just perfect.

(Also, I think I have that exact purple sari that becomes Katyayani’s signifier. It was a gift, from one of my closest friends.)

Hovering between history and fiction is Amita Kanekar’s Fear of Lions. Set in the 17th century, in Mughal emperor’s Aurangzeb’s reign, the novel is about a rebellion by a group of people whom no one considered a serious threat – until their influence extended to the outskirts of the capital city, Shahjahanabad (modern-day Delhi).

Being mostly clueless about Indian history, I had no idea that Kanekar was writing about a real, historical event. For those who are like me, here’s the history. In 1672, Aurangzeb sent 10,000 troops to crush a group of rebels who had advanced to the outskirts of Shahjahanabad. The rebels belonged to a sect known as the Satnamis and their rebellion had started in 1657. Founded by Birbhan and inspired by Kabir, the Satnamis rejected the caste system, gender hierarchy and also demanded tax reforms.

Now for the historical fiction. Fear of Lions opens with the death that sparked the rebellion. For most of the characters in the book (and readers like me), who don’t know what happened between 1657 and 1672, it’s just a random killing. How that rebellion by those who are eventually identify themselves as “Followers of Truth” is related to the charred bodies lining the roads and the whispers about a terrifying group of warriors (who have gun-toting women in their ranks!), is the story of Fear of Lions.

Alongside the rebellion by the Followers of Truth is a smaller act of revolt. A young noblewoman has decided she won’t submit to the arranged marriage that is expected of her. Instead, she plans an elaborate elopement, involving her maid (who is in the know) and her brother (who isn’t). As far as she’s concerned, it’s a minor detail that she hasn’t informed her paramour that she plans to show up at his tent (he’s an officer in Aurangzeb’s army).

Through the aristocrats, Kanekar offers richly-realised tableaux of Mughal society and all its privilege and decadence. The careless violence, the beauty, the corruption and the cruelty – it’s all here.

As well-written as these sections are, I have to admit, I tired quickly of these spoilt-brat aristocrats and found my attention wandering. The pace of Fear of Lions sags after a crackling opening, weighed down by the detailing that Kanekar has embroidered into the narrative (from fabric to architecture, everything is described with the meticulousness of a historian). But if you stick with the book, Kanekar rewards your patience with a unicorn of sorts: Narnaul.

The town is a nondescript place today, but in Fear of Lions, it is a utopia fashioned into reality by the Followers of Truth who set up their own administration after rejecting the authority of the traditional landlord. In this new Narnaul is a society where women work and fight alongside men, wield guns expertly and are leaders of the community. There’s no caste system and people treat each other as equals. There is dignity in labour here and respect for every member of society. All this in the 17th century. I was certain this was the fiction part of Kanekar’s historical fiction until a little digging around introduced me to the ideas of the Satnami sect and the fact that the Satnamis did in fact set up their own administration after their revolt of 1657. I’ve no idea if it was as actually as vibrant a place as what Kanekar imagines, but whatever they set up must have felt like freedom (especially considering the rigid and exploitative hierarchies that dominated so many other parts of the country).

One of the things that Kanekar shows is how the Mughals actually helped maintain the caste system because they could use the inequality to maintain their own power base. Ultimately, alliances are about power rather than religion or any other metric. In case of the Followers of Truth, their community is an alliance between people who don’t share any traditional social ties, but are bound by the fact of being at the bottom of the social pyramid. Theirs is an alliance of the powerless.

The story of the Followers of Truth is shrouded in secrecy because no one in the circles of power wants it to be known that a group of social outcasts had almost brought the Imperial army and authority to its knees. Perhaps even more frightening is the seductive power of the Satnami philosophy. Those in power have no intention of letting those they oppress get a whiff of the freedom that Birbhan and the Satnami philosophy offered followers. The efforts to vanquish the Satnamis succeeds to a large extent, but in this defeat is also their victory. Nothing shows how dangerous an idea is than the use of excessive force to wipe it out.

Doggedly curious to find out what happened in Narnaul is an intelligence officer, Abul Mamuri. Mamuri is a man of many layers, complicated history and mixed heritage (much like the idea of India herself). As he winds his way through kothas, palaces, inns, army tents and bars, we find out what happened to both the Followers of Truth and the rebellious noblewoman.

Incidentally, what I really would like to read is a series of historical fiction starring the intelligence officer, Abul Mamuri. What’s not to love about a tubby hero who can blend into the crowd when needed and eke out secrets from people using wit and wile?

You can read an excerpt from Fear of Lions here.

Finally, Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that this volume of nine essays is well-written. Tolentino is a staff writer at The New Yorker. She had previously worked with The Hairpin (which, while it lasted, was a fantastic website for writing on subjects concerning women) and Jezebel (which describes itself as “a blog geared towards women”). If you haven’t read Tolentino’s writing, then this archive is a good place to start (it has excerpts from Trick Mirror too). All the pieces are long and most of them are both insightful and satisfying.

Unrelated to Tolentino’s writing skills, it struck me while reading Trick Mirror that the fact that the pop culture that she references is easily relatable to a reader sitting in another continent, belonging to a different age group and cultural background, is more evidence of the new-age colonisation by American entertainment and media. Yoked into a herd by trending topics and hashtags; influenced by the same shows (that nevertheless must impact viewers very differently depending upon their immediate, real-life contexts), ours really is becoming a small world after all. This shrinking must bring with it a certain amount of flattening, which is alarming because I don’t think we’re alert to it. But the silver lining is that as a result of this herding, an essay by a Canadian-born, American writer of Filipino heritage titled “We Come From Old Virginia” ends up feeling timely to a reader in India whose mental references of Virginia are limited to a brand of cigarettes (specifically their vintage ads) and a fragment of a lyric from a song by John Denver.

In “We Come From Old Virginia”, Tolentino writes about a story about campus rape that was published by Rolling Stone and which turned out to be a fake allegation. American campuses have a reputation for being safe spaces for predators because predatory behaviour is almost equated with a rite of passage (like ragging in Indian colleges, for example) and authorities don’t encourage women to file official complaints. The journalist who had written the story for Rolling Stone had not corroborated the account as rigorously as she should have. Why? Because it rang true.

“The choice is not always between being sincere and untruthful. It’s possible to be both: it’s possible to be sincere and deluded. It’s possible – it’s very easy, in some cases – to believe a statement, a story, that’s a lie,” Tolentino writes in the essay.

Ironically, the ‘bad’ journalism that Tolentino describes in this essay is still a darn sight more meticulous than most of the journalism done by the Indian media on #MeToo allegations, but that’s another rant for another day.

I’ve lost count of the number of times men have brought up the issue of false allegations in the middle of a conversation about feminism and violence against women. Reading Tolentino analyse false allegations, sexism and predatory behaviour without any knee-jerk reactions was such a relief. This essay is one of the most considered explorations into this subject that I’ve read and it felt particularly pertinent because when I was reading it, Twitter was aflame with a he said-she said spat (Utsav Chakraborty’s takedown of allegations made by Mahima Kukreja. If these names don’t ring a bell, please don’t fret. I genuinely doubt this episode is the make-or-break moment for the feminist dialogue India).

One of the sharpest and most heartbreaking points Tolentino makes is when she quotes a section from another essay about the (limited) power of a woman’s story. When an allegation sounds “ordinary, mundane, eminently forgettable, like a million things that had happened to a million other women”, it isn’t just a bit of fiction. The subtext of a false allegation is the spectrum of predatory behaviour that is accepted as normal and not worth reporting or outrage. In the Indian context, I would add another layer to this, but I’ll spare you my hot take.

I enjoyed how Tolentino collects and collates ideas in essays like “Pure heroines” (on English literature and its heroines), “The Cult of the Difficult Woman” (on feminism as a marketable product) and “We Come From Old Virginia”. A lot of her personal stories, — like growing up in a conservative, Christian society; her experiences as a member of the Peace Corps; the similarities she felt between a drug-induced high and epiphanies — are very engaging. That said, I do think Trick Mirror would feel more potent to a reader in America or familiar with the experience of living in America. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the essays that resonated most with me had to do with femininity and sexism in contemporary, urban society. The only thing connecting us more deeply than Netflix is the fact of being a woman in a male-dominated world.

Though that reminds me of a prickly question. Someone asked me whether Trick Mirror would be interesting to a male reader and my first reaction was to bristle. Exactly no one asks me whether, for example, Simon Schama’s The Power of Art is written for one particular gender, so why Tolentino’s book? Because she’s a woman? Because she’s a feminist? Because the person asking the question is a twit?

And then I thought about what I just told you, about which of the essays stayed with me. I also thought about all the books written ostensibly for boys that I’ve enjoyed since I was a child. Most of them were not intended for readers like me (i.e. those that identify as feminine). Still, I got lost in them. This was partly because they were well-written, but also because I was an eager reader.

So I guess the proper answer to the question (of whether a man/ boy would enjoy Trick Mirror) is that it depends on the kind of reader you are rather than where you find yourself on the gender spectrum. Never mind your body parts. Are you curious? Then you’ll find a lot to enjoy in Trick Mirror and who knows, you may even find yourself reflected in it.

Thank you for reading. Dear Reader will be back soon.