Fierce Femmes + The Silence of the Girls + The Arsonist and more

I’m writing to you because I have, in the words of the youth, legit forgotten everything I’ve read since I last wrote. Which means it's been entirely too long since I sent out this newsletter. So without further ado, here’s what I do remember of what I’ve read.

I finished Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, a retelling of the Iliad from the perspective of women who were kept as prisoners and slaves. Instead of celebrating the warriors who won or fell, this is a story that offers an alternate model of heroism – one in which heroism lies in patience, resilience and survival. The narrator is Briseis; once a queen, now a slave. But a privileged slave because she is the ‘possession’ of the great Achilles. Barker's novel is an elegant reminder of the narratives that have been lost, suppressed and ignored because of our blinkered fascination for the alpha male hero. It also offers a look at what behavioural traits the Iliad (and its translations) privileged in creating the ideal male.

Especially since a lot of us have the original Iliad seeded in our imaginations, The Silence of the Girls offers a perspective that gives you a less conventional take on war because it pays as much attention to the consequences of defeat as the euphoria of victory. Barker also pays attention to how narratives and history are created and framed, which is viscerally relevant to us today when so much of the world is plunged in strife and war-like situations. While reading The Silence of the Girls, I kept thinking of the way groups like Boko Haram and the ISIS have abused countless women and just around the time I finished the novel, news started trickling in of how the Janjaweed had massacred hundreds in Sudan in June. I wonder if those women would even be interested in reading a book like The Silence of the Girls if they were able to access it. I wonder how they'd respond to it if they did read it.

While I enjoyed The Silence of the Girls and would recommend it to epic/ Greek mythology geeks in particular, I must admit I wasn’t exactly blown away by the novel. I think my biggest issue with it is that for a book that seeks to reimagine a male-centric epic, The Silence of the Girls is still focussed on the men and too little of the internal lives of the women develops over the course of the novel. Also, the style that Barker chose for this book – a blend of colloquial and old-fashioned English – felt jarring occasionally. For example, the modern register made Briseis’s voice sound distinctly un-epic even though the setting is ancient Greece with river nymphs showing up and curses being unleashed. There's nothing wrong with that, but for the fact that it lacks harmony. The other thing the novel lacks is a sense of urgency and conflict. Even when Briseis says she’s scared or feeling unsure, she seems safe. There’s a regal entitlement to her that you know will protect her (also, she’s the first-person narrator. Without her, there’s no novel). Plus, both the Iliad and the Odyssey are so familiar because of the number of times they’ve been retold (in multiple media). In the words of Barker’s Briseis, “we need a new song.”

That said, I do find myself imagining a reader who comes across retellings like Barker’s The Silence of the Girls or Margaret Atwood’s Penelopiad, and then the Homeric epics. Which character would get first dibs on the idea of a hero in that reader’s imagination?

Curiously, what felt far more epic to me than The Silence of the Girls was Ki Cheng Thom’s Fierce Femmes And Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir.

Thom describes herself as “a writer, performer, lasagne lover, and wicked witch based in Toronto”, which actually gives you a good sense of the kind of book she’s written. Just as the bio is neatly balanced between serious (writer, performer) and weird (lasagne lover, wicked witch), so is the book. Thom’s story starts off in “a crooked house in the heart of gloom” where the child of an exhausted Chinese couple chafes against the male body and the expectations that come with it. Armed with the kung-fu and a few worldly possessions (including a knife), the trans girl runs away and finds her tribe on the strange streets of a city that shimmers between reality and magic. Fierce Femmes is violent, weird and richly poetic in its descriptions of how a group of trans women love and damage each other in equal measure.

There’s nothing realistic about Fierce Femmes, but its descriptions of the anxieties, fears, insecurities and comforts feel authentic and relatable. There may be no physical detail of that world that you recognise, but the way these characters feel driven to compete with one another; the struggle between wanting to comfort and needing to dominate – it all feels curiously familiar because I think too many of us find ourselves in circumstances where society pits us against one another.

One of the deep joys of this book is Thom’s language. She tosses gorgeous, evocative phrases that explode like fireworks against the background of the rest of her prose. One of my favourite sections in the book is a poem to long hair, which is essentially about waiting and watching for one’s hair to grow out:

“my hair is dreaming itself

longer and freer, wilder and tangled,

it dreams itself snarled and knotted and restlessly windblown.

my hair is dreaming and becoming, becoming

and dreaming, dreaming and becoming and

becoming and becoming.

my hair is becoming long enough…”

It's just hair, right? But of course it isn't. You can feel the longing that the writer has for all the femininity that is associated with long hair as well as the impatience and restlessness that you feel when the hair just doesn't seem to grow fast enough. I also love the idea of hair dreaming itself as something different. Move over Rapunzel.

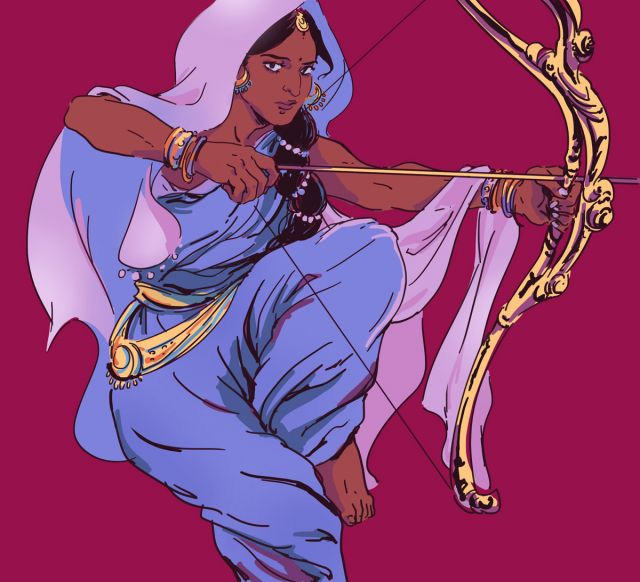

Fierce Femmes doesn’t read as though it’s been written to educate readers about trans identities and perhaps trans folx reading it will find a lot more insight and richness than I’m able to appreciate as a woman who doesn't feel a dissonance between her gender and biological identities. What I can say as a reader who isn't trans is that I'm glad that the femmes of this book are entering our literary landscape. There isn't a preachy moment in this book and yet it serves as a potent reminder of how few trans characters feature in contemporary literatures. Fierce Femmes also made me wonder about the ways in which our storytelling traditions have celebrated and failed characters like Brihannala and Shikhandi from the Hindu epics. Think about what they're written in the stories, and how you remember them being depicted in artwork/ TV series/ theatre etc.

(This is Brihannala as imagined by a Chinese illustrator on Tumblr.)

And now for the book I’ve abandoned – Kiran Nagarkar’s The Arsonist. If you think I abandoned it because he’s been accused of behaving inappropriately by multiple women, feel free to pick up the book and let me know how many chapters you get through before you admit defeat. Last year, when the allegations against Nagarkar surfaced, the publisher who had rights to The Arsonist dropped the novel, which was interpreted as the publisher taking a stand. Not that I have any proof to this end, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the allegations were an excuse to rid themselves of an unwieldy work. Because the first 120 pages of this 302-paged novel are tiresome, preachy and dreary – words I didn’t think could be associated with Kabir.

Kabir – born to a Muslim family, disciple of a Hindu guru, and revered by both communities – raised hackles in the 15th century because he was such a non-conformist. He spoke up against hierarchies of caste as well as gender. He dismissed doctrines, rubbished rituals; he questioned relentlessly. And he wrote his radical poetry in simple language. Given the kind of discord that has been sowed in India in recent times, of course it’s tempting to imagine how someone like Kabir would negotiate the toxicity that surrounds us today. This is what ostensibly Nagarkar wanted to do and it’s obvious that The Arsonist wants to be the book that rattles authorities the way Kabir did to those in power in his time. In the first 120 pages, it’s full of monologues that are utterly convinced of their own awesomeness and unaware that most of the cleverness feels tinny and almost frivolous. One reason for this is that Nagarkar hasn’t bothered to root them in a context. It takes a while to figure out in what time period The Arsonist is set. Chances are that Nagarkar wanted the novel to feel timeless. Unfortunately, the lack of specifics means the world-building loses definition and Kabir's reality feels artificial as a result.

It is, of course, entirely possible that The Arsonist lights up and becomes incandescent from precisely the point at which I abandoned it. Perhaps it starts paying attention to pedestrian things like giving the reader a sense of place, building character arcs, introducing tension and conflict. All I’ll say is that the last two-thirds of the novel have to be insanely brilliant to make up for the dreary mess that is The Arsonist till page 120.

Incidentally, I stopped at page 120 because Kabir is believed to died when he was 120 years old.

*

On the essay front:

Looking at Photographs of Marilyn Monroe Reading

"Her marriage to Arthur Miller was made out to be an unthreatening and cartoonish case of odd couple in the press (“The Genius and the Goddess,” “The Brain got the Blonde,” “Egghead weds Hourglass”) to distract from what was essentially political identification and intellectual self-fashioning by way of romantic partnership. If Marilyn Monroe was only ever understood in the terms of sexual desire, then who she chose to sleep with became one of her primary modes of communication to the public. Post-Freud yet pre-Foucault, she, of all people, understood that who and how you desire has material consequences."

These Women Reporters Went Undercover to Get the Most Important Scoops of Their Day

"Their reporting had real-world consequences, increasing funding to treat the mentally ill and inspiring labor organizations that pushed for protective laws. And they were so popular that, while in 1880 it was practically impossible for a female reporter to get off the ladies’ page, by 1900 more articles had women’s bylines than men’s."

Why the power of cute is colonising our world

"This ‘unpindownability’, as we might call it, that pervades cute – the erosion of borders between what used to be seen as distinct or discontinuous realms, such as childhood and adulthood – is also reflected in the blurred gender of many cute objects such as Balloon Dog or a lot of Pokémon. It is reflected, too, in their frequent blending of human and nonhuman forms, as in the cat-girl Hello Kitty. And in their often undefinable age. For though cute objects might appear childlike, it can be strikingly hard to say, as with ET, whether they are young or old – sometimes seeming to be, in human terms, both."

A Universe of One’s Own

"If we examine the history of literary achievement (a critical mass of awards, magazine profiles, reviews, inclusion in anthologies and course offerings), it is largely white, male, and middle class—a homogeneity enabled by a similar constituency in the editorial departments of periodicals and books. In Silences, her groundbreaking 1978 survey of the American publishing industry, Tillie Olsen found one female writer of achievement for every twelve male writers. The gender and racial makeup of publishing in all its forms is beginning a slow shift (with quite a long way to go), and with it has come a wealth of rediscovered voices, many of them female, and in a variety of genres.

But it isn’t enough to recall these “lost” writers; it is equally important to understand how history overtook them in the first place, a reconsideration of what we thought we knew—a form of time travel in which the present transforms the past."

And finally, some wonderful contemporary Indian poetry in English.

*

Before I sign off, I wrote a few things that some of you might find interesting. First up, there's a retrospective of sculptor Mrinalini Mukherjee's works at the Met in New York. Mukherjee was the daughter of Benode Behari Mukherjee, a legendary teacher and an incredibly-gifted artist. Her art was nothing like her father's. It's weird and magnificent, and I wrote about it here.

Then there's this love letter to the clouds of Bengal.

Less pleasant was the experience of watching director Sandeep Reddy Vanga's interview. Vanga is the director of Arjun Reddy and Kabir Singh, two enormously successful films that celebrate toxic masculinity. I had a violent reaction to watching his interview.

*

Thank you for reading, sorry for the typos etc. Dear Reader will be back soon.