Dear Reader,

A couple of months ago, I did something that could be described as stupid. I gave out my postal address as part of a books exchange. It wasn’t as though I was sharing my address with complete strangers (though, to be fair, I have done that in the past too. What? None of you had pen pals?), but rather I was trusting people I knew (some more vaguely than others) to share it responsibly.

The exchange worked on the principle that the participants belonged to loosely-connected circles of friends. I knew the person who brought me into the challenge but didn’t know the person to whom I sent a book, and I’ve no idea who would send me books as part of the exchange. So yes, there are complete strangers who have my address while I have a pile of excellent books sitting pretty in my living room. Security hazard? Potentially. Satisfying? Gods, YES.

There’s something about this exchange that felt perfectly suited to lockdown. It’s a connection made up of remoteness and being disconnected. Most of the rituals of the exchange happened online, with no contact between sender and receiver. The messages were exchanged on Instagram. The books were sent using either Amazon or bookstores that do deliveries. There was no note or post stamp to clue you in about who may have sent a book. Yet, despite this anonymity, there’s something strangely tender and personal about the exchange. You know that the sender probably took some time to decide what book they would send you. It’s not a random choice. It’s a gift without the performance and tags of acknowledgements that most online campaigns have these days. The sender doesn’t know the receiver, but they’re sending a little bit of themselves with the book they choose. There’s no other message that a sender can add beyond the book itself just as there’s no other way to thank the sender than by reading the book.

This is the sort of sharing that famous and careful people should not do. I, however, am neither. You’re looking at a person who as a kid, signed up for every postcard exchange she could find; and as an adult, I have cheerfully let people I knew only on the internet into my home (among the best decisions of my life, thank you very much). I’m also the sort of person who champions DuckDuckGo and scrutinises photos to make sure they’re not revealing before uploading them. So yes, it doesn’t make sense, but it does add up.

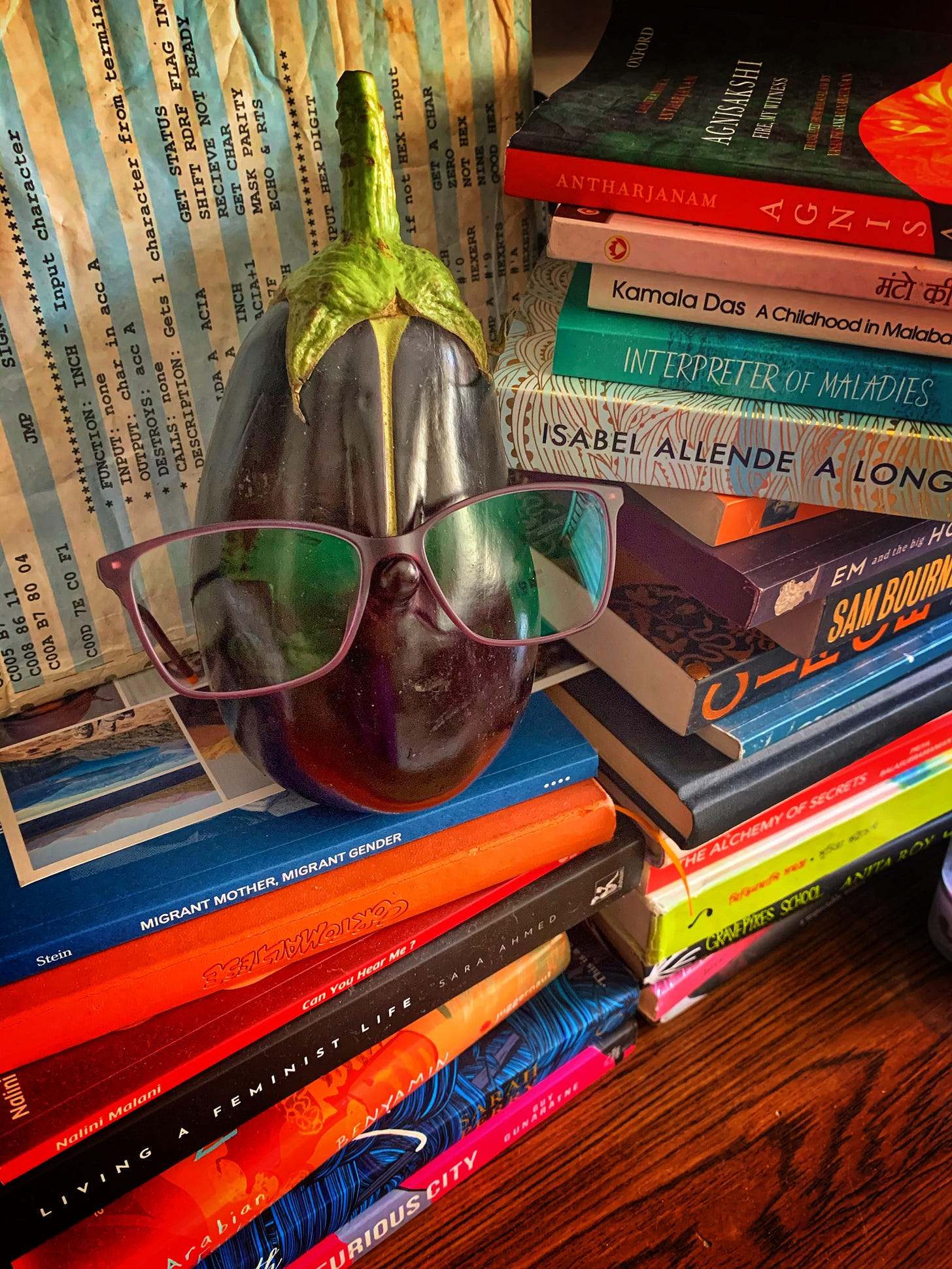

Bottom line: Thanks to this exchange, I am now the proud owner of a pile of excellent books, many of which I haven’t read. Coincidentally, around the same time I procured a rather erudite aubergine (not as part of the books exchange. That would be very weird).

The best part of exchanges like this one is that it brings you books that you didn’t know existed. Like I had no idea that a gent named Greg Jenner (not related to any Kardashian) had written Dead Famous: An Unexpected History of Celebrity from Bronze Age to Silver Screen.

Jenner’s book is packed with superb stories of people you may know and some you definitely don’t because very few celebrities remain famous over time. Covering roughly three centuries (with a few detours to the ancient Greeks and classical Romans), Jenner doesn’t go through the history of celebrity chronologically. Instead, he zips between time periods while examining different aspects of celebrity culture. Jenner’s central argument is that the definition of celebrity can be held as a constant across the ages. Helpfully, he has a checklist for what constitutes celebrity:

Unique personal charisma

Being widely known to the public

A brand disseminated by widespread media

Private life consumed as dramatic entertainment by the public

Commercial marketplace based on celebrity reputation.

You wouldn’t think one set of criteria could apply to everyone from Julius Caesar to Sara Baartman (who was displayed as the “Hottentot Venus”), but Jenner makes a solid case for his theory. He stops his study in the 1950s, which is a shame because after reading his description of Gertrude Stein (“modernist Miley Cyrus, minus the twerking”) and Lord Byron (“talented, pouty shag merchant with lustrous hair”), I really want to know how he’d read today’s hotshots.

The way Jenner sees it, celebrity is “a form of harmless radioactivity” that may not cure cancer, but it does give celebrities a biology-altering power for a limited period of time. In regular mortals, celebrities can cause a range of bodily symptoms, including “sweating, increased heart rate, gabbling, stunned silence, shrill screaming, hysterical crying, and uncontrollable lust”. It’s both mysterious and man-made, which means we can’t quite predict how it will work, but people have used it to serve personal and professional agendas.

Random trivia: the ancient Greeks had a goddess of fame, Pheme, who became Fama, the ancient Roman goddess of rumour. Homer said Pheme was a terrible gossip and the messenger of Zeus. If she favoured you, you became famous. If she didn’t, you became the subject of scandal. Fama got a much rawer deal from Virgil, who described her as a “dreadful monster” who needs neither sleep nor shelter; she travels fast and grows in size as the rumours grow in popularity. In short, Fama’s “less goddess, more B-movie monster intent on trashing Tokyo”.

Jenner really, truly has a way with words.

He’s also collected some fantastic stories that range for horrible to weird. For instance, did you know Gertrude Stein advertised for Ford Motors? Or that in the 1890s, psychologists were diagnosing many men with Americanitis? It was the nickname for a novel disease that supposedly made strong, virile men feel weak and depressed because their brains couldn’t handle the sudden rush of information coming with new technologies like the telegraph. Around the same time, and long before Brangelina, there was Cléopold, the portmanteau for an alleged affair between ballerina Cléo de Mérode and King Leopold II of Belgium (best known for brutalizing the Congo). Mérode did many scandalous things in addition to possibly canoodling with one of the cruellest European tyrants. She appeared nude in a play and posed for a nude sculpture, but guess what part of her fascinated the public most? Her hair-veiled ears.

Then there’s the truth behind the cutesy films of the 1930s, around the time when Shirley Temple was scaling the celebrity ladder as a child star. Here’s how film producers made sure kiddie actors behaved themselves on set:

“…the producers built a soundproof, cramped box in which was stored a large block of ice. This cell was used to punish naughty cast members, with the troublesome toddlers being made to stand in the cold, or even sit directly on the ice, until they’d learnt their lesson.”

And we complain about Tiger Moms.

One of the most refreshing aspects of Dead Famous is that it’s not all white people, despite being focused on Europe and America. Jenner takes time to bring in marginalised people like Baartman, giving her the respect that few did when she was at the height of her fame. He also spends some time with our very own Ashok Kumar, Bollywood’s first superstar, and Fearless Nadia who “was Clark Gable and Katherine Hepburn combined” and “kicked like a mule”.

Along with being respectful and empathetic, Dead Famous is also one of the most fun books I’ve read in a while. We’re so used to celebrity culture being either savaged or celebrated that it’s easy to forget that these binaries are not the only perspectives on celebrity. Jenner is critical, sensitive and thoughtful in his examination of celebrity culture and how mainstream media and the capitalist drive has turned celebrities from like products. Plus, bibliography has also added a lot of books to my reading list so all in all, everything’s right with Dead Famous.

Another thing the book exchange did for me is save money — because some of the books I got were coincidentally ones that I’d planned to buy, like Gretchen McCullough’s Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language. I came across McCullough’s book a few months ago while Googling an acronym that someone had flung at me, imagining me to be much more hip than I actually am. It’s not just that I don’t know the acronyms. I seem to also have a gift for forgetting their full forms and remembering wrong versions. For instance, I’ve Googled TWSS (which is not “Trigger Warning Some Said” or “That Weird So-and-So” but “That’s What She Said”. I think) at least 20 times. The last time was yesterday.

But never mind me and my inability to memorise things. McCullough is a linguist and Because Internet is an exploration of how the internet is changing the English language and its usage. For instance, it turns out that there’s actually a pattern to the string of gibberish we often write when we can’t find the write words to express an intense emotion, usually rage or frustration (it’s called the keysmash). When done on keyboards, keysmashes almost always begin with ‘a’. On smartphones, keysmashes often start with ‘g’. Also, a lot of the internet English that we may think to be new is actually old. For example, all caps to indicate shouting dates back to the 1940s and the first example that McCullough found of repeating letters to show emphasis (like “noooooo” or “heeeeere”) was from 1848. Also, “hi” dates back to at least the 1400s.

For a lot of us, the internet still feels like a new place and Because Internet is a good reminder that not only has it been around for almost 30 years now, these decades have also been eventful. The history of the internet is dense because so many have used it and the medium has proved to be both malleable and responsive. For linguists, the internet is a treasure trove because it has so much writing that is informal and publicly accessible. It’s almost like having a record of how languages have changed in real time.

Focussing on English, McCullough examines some of its “exquisite layers” (I love that phrase to describe language) and weaves in strands from other people’s studies of language and writing on the internet. Also, here’s a fact that linguists are apparently bored by but which has properly blown my mind — across centuries and languages, women have always led linguistic change. I repeat: across centuries and languages. This is fascinating, especially since the bulk of our recorded histories are of patriarchal societies in which women had barely any agency. And yet, somehow, women are the ones who have decided the courses that languages have taken. No one knows why, but women, particularly young women, are language disruptors who introduce linguistic changes. Men follow a generation later, which suggests they learn language from their mothers.

One of my favourite chapters in McCullough’s book is the one on emojis, explaining how they began to the rules that govern them today. She also makes a point that seems so obvious after she explains it: add-ons like emojis and GIFs “restore our bodies to our writing”. They’re gestures, much like the hands we wave and the eyes we roll while talking. Except by using these external bodies — made of multicoloured blobs in case of emojis and other creatures’ bodies in case of GIFs and stickers — it’s almost like we’re expanding the scope of our physicality, but by taking it away momentarily from the other person. I, for instance, can’t actually replicate what that GIF did up there, but taken out of context, that moment is an accurate physical expression of my emotion even though that woman and I have absolutely nothing to do with each other. Sometimes, when using gestures like GIFs, we’re removing the original character’s story; it’s like a virtual body snatching.

There’s a lot of fantastic trivia packed into Because Internet and as a bonus, McCullough is also a very funny writer. I’m forever grateful for her insightful observation that sending someone all the birthday party emojis shows you’re feeling extra festive, but sending all the possible phallic emoji (eg. the eggplant, cucumber, corncob and banana) is not extra sexy, but “a weird salad”. The part that really stayed with me though is where McCullough discusses how we change our language depending on our audience. To illustrate this point, she notes that while talking to coworkers, no one is likely to say something along the lines of “Who’s a good boss! Do you want to go for walkies and also give me a raise? Yes? Yes! No? Boop!” While I take her point, I do think it’s a damn shame that this is neither done nor does it work because appraisal season would be infinitely more enjoyable if it did.

I’ll leave you now with the image of booping your boss or coworker. You’re welcome. Take care, stay safe and thank you for reading. Dear Reader will be back soon.