Crow-women, testosterone, djinns and more

Dear Reader 1.6

Dear Reader,

Just as I was sitting down to write this newsletter, I got an email telling me someone had unsubscribed. I can’t blame her. It has been more than a month since the last one and this is supposed to be a weekly affair. The rest of you who have not unsubscribed, thank you for your patience and happy new year!

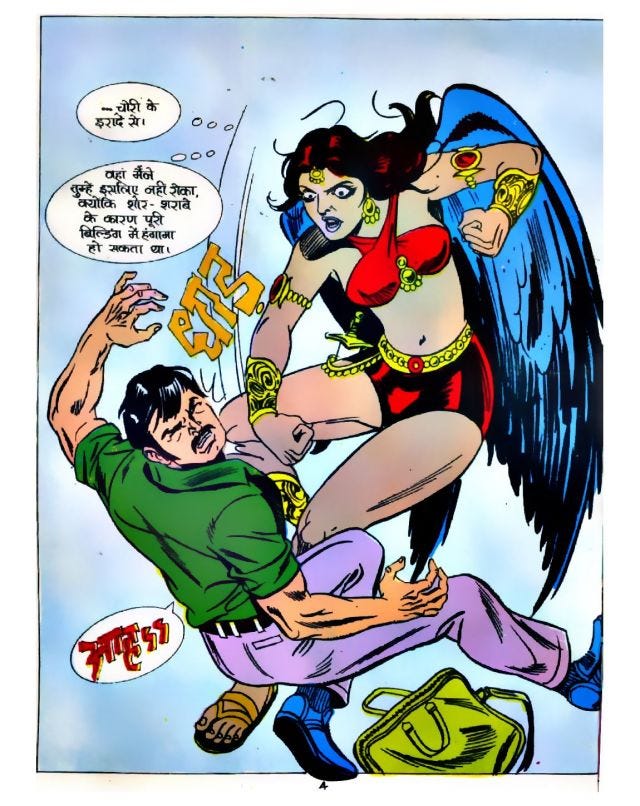

That’s from an Indian comic I chanced upon while writing this article on the Indian comics scene. She’s a crow-woman called Kanga, stranded on earth because she’s been left behind by other crow-people. Now she goes around cawing and helping the police hunt criminals. Kanga stands out not just that she has these ginormous wings, but because her skimpy outfit shows a strikingly muscular figure. What I found interesting was that the world of grown-ups (all men, naturally. Insert eye roll here) don’t understand her. Even though we as readers know and understand her thoughts, when she opens her mouth to the others in her world, all the men hear are caws. It’s just cacophony. It’s almost like a statement on how strong women who don’t cower before men are perceived. Like an idiot, I didn’t bookmark the link where I’d found a few Kanga volumes. If anyone knows where I can see them again, do tell.

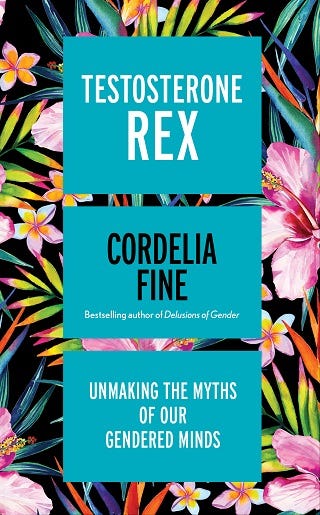

On the subject of gender biases, this year, the Royal Society prize for science book of the year went to Testosterone Rex: Unmaking the Myths of Our Gendered Minds (Icon Books) by Cordelia Fine. It begins with Fine’s son suggesting at the dinner table, that after neutering their dog, “we could have his testicles made into a keyring!” I immediately picked up the book (from Wayword and Wise in Mumbai, which used to be one of my favourite bookstores. The collection is still fantastic, but I’m appalled at how sloppily the books were kept the last time I visited. Torn covers, dirty jackets, snubbed corners — all accompanied by a careless shrug from the gentlemen at the cashier. For the first time, I left the bookstore in a furious grump and with only one book. Sigh).

Aside from a gorgeous cover and a winning opening, Testosterone Rex offers a sharp and savage critique of the idea that gender stereotypes are rooted in biology. Scientifically speaking, Fine argues that gender differences are minimal and the biases in favour of men privilege a vision of aggressive masculinity related to testosterone. Stereotypes are cultural constructs, Fine argues, and the sooner we acknowledge that, the better — and more robust — our science will be. Fine is brilliant at making complicated, academic studies seem accessible and easily comprehensible. She’s also extremely funny, which helps because halfway into the book, you may just feel exhausted that she has to repeat herself again and again to stress what seems obvious: gender is socio-cultural, rather than biological. That said, I found her message repetitive because I’ve bought it. There is, however, a wealth of research that has gone into substantiating the opposite of what she’s saying, asserting that it’s our biology that makes women weaker and meeker. Kudos to Fine for having the patience to analyse and point out the weaknesses in scientific studies that have been reviewed and validated. Start focusing on how she tears these studies apart, rather than the ultimate conclusion, and this book becomes a triumph.

Reading The Nine-Chambered Heart (Fourth Estate, Rs 399), you can’t help but wonder at how pervasive these constructs of masculinity and femininity are. With four more chambers than Anais Nin’s, Pariat’s novel is about a woman as seen by nine characters. Most of them are ex-lovers. Each one remembers the time that they’d shared together, describing what about her drew them and what drove them apart. Through this, we’re to gather details and create a portrait, sifting through the stories to find pieces of her. Pariat has said in interviews that it’s 57.8% based on her real life, in case you were wondering.

I don’t have my copy of novel with me as I type, so I can’t tell you who designed the cover, but the designer deserves a year’s supply of cupcakes. It’s a luminous image of scattered petals that go from fragile, transparent white to delicate, blushing pink and a thicker, bleeding fuchsia-red. It’s the kind of cover that makes you pick the book up. It also hints at something else about the book: how romanticised it is.

Pariat is an amazing wordsmith. Her prose is a delight to read because she chooses every phrase with care, folding them into sentences that are intricate and beautiful. Read this excerpt, which is from the opening chapter and perhaps my favourite part of the book. Titled “The Saint”, the narrator is a teacher and his account tells the reader as much about him as it does about the girl. Some of the information is delivered in obvious ways, like when the teacher asks around about the student and finds out she lives with her grandparents and doesn’t see much of her parents who are working elsewhere. But there are much more subtle little deliveries too. Like the way the teacher is unsettled by her and how his uncertainty about how to behave with the girl betrays both his own insecurities as well as his ego. Meanwhile, there’s this quiet, stubborn, angry girl who finds her artistic skill in origami — a precise, artistic practice that depends upon following strict instruction and meticulous attention to detail. It’s tinged with the exotica of being a foreign craft and it’s not a group activity.

Unfortunately, not all the chapters in the book are as masterfully drawn out. As the tales add up, what looms uncomfortably over the book is the absence of the woman herself. She is an object that never quite becomes the subject because the tellers — and this is true to real life — actually want to talk and justify themselves. By the time The Nine-Chambered Heart travels to Italy, I felt a strange sense of dreamy artificiality. Everything was beginning to feel like a postcard. With each successive chapter, the woman became increasingly distant and unreal; an exotic and mysterious lover, fuzzily-outlined. If these were simple love stories that were being unravelled, perhaps I’d have accepted the absence of the woman easier. But this is a novel in which physical and emotional violence is inflicted upon her repeatedly. And so it is that I find myself reading a story of a silent victim, whose traumas I’m supposed to glide past because another man wants to boast about how he loved her not wisely but well. We never see her side of the story, we never hear her voice, we never even really see her through her own eyes and all this fills the novel an uncomfortable silence.

If you’re unsure about whether or not you’re a nerd but would like confirmation either way, please read The Book Hunters of Katpadi (Hachette, Rs 599) by Pradeep Sebastian. If it bores you, you are not a book nerd. Sebastian though is a book nerd. I've never met him, but it’s obvious in every page of this novel which calls itself a “bibliomystery”, but is really just an excuse for Sebastian to toss in charming anecdotes about vintage books and their collectors.

Set in Chennai and Ooty, the novel is ostensibly about a set of documents that are believed to be written by Orientalist Sir Francis Richard Burton. Tasked with first acquiring this material and then figuring out what to do with it if it's original are Kayal and Neela. Neela owns an antiquarian bookstore in Chennai and Kayal works for her. Their clientele include gentlemen like the delightfully-named Nallathambi Whitehead and Arcot Templar, who are passionate collectors of rare, antique books.

There could have been a cracking good story here about male egos, deceit, the competitive world of what seems like a luxurious hobby, and cracking language to figure out authenticity.

Tangent: If you have Netflix, please watch Manhunt: Unabomber. It’s all about language and the codes embedded in the words we choose when we write. Super stuff. Also, it has Paul Bettany, who aside from being ridiculously talented is still scrumptious. Even with a scruffy beard and crazy hair. Yes, there is a gratuitous shirtless shot, for those who were wondering.

Coming back to The Book Hunters of Katpadi, the novel is lovingly produced, though I wasn’t blown away by Sonali Zohra’s illustrations. They’re pretty enough, but ideally illustrations should add to the storytelling rather than simply illustrate. Zohra’s drawings do the latter competently, but you could ignore them and you wouldn’t miss much.

The real problem is that the hunt is actually the least interesting part and while the plot trots at a steady pace, the question of whether Burton’s papers are authentic never feels urgent. It’s glaringly obvious that Sebastian is in it for the antiquarian gossip and if you’re a book nerd, you will love the stories about bibliographers like Thomas Frognall Dibdin (love that name. Calcutta-born, thank you very much). I had a great time reading this and I genuinely didn’t give a toss about the mystery because I love the world that Sebastian creates in the novel. Sun-dappled balconies, libraries that aren’t dusty and are full of beloved books, a languid Chennai of bookshops, streetside snacks, students and geeks, and people poring over manuscripts and sniffing pages — who needs suspense and drama when you have all this? (Ok, it would have been better with suspense and drama, but this is still a joy to read.)

Saving the best for last, my favourite read of December is Saad Z. Hossain’s Djinn City (Aleph, Rs 499). We don’t have enough South Asian fantasy for grown-ups, so this is a welcome addition to the shelves.

It’s got all the standard tropes: a neglected kid, an eccentric father, an old enchanted house, malevolent enemies from a parallel magical world, dragons. Except this isn’t for kids even though one of its protagonists is a 10-year-old. This is why I'm glad that Aleph went with the second cover, rather then whirling, green one. Artistically, the green one is nicer, sure, but the Aleph cover makes it quite clear that this is not desi Harry Potter by a long shot.

Indelbed lives in an old house with his father Kaikobad and a few loyal domestic help who remain despite Kaikobad being a penniless drunkard. While their personal fortunes may be ruined, Kaikobad is one of the illustrious Khan Rahmans of Dhaka, which means the extended family shows up to wag a finger at Kaikobad’s parenting. By and large though, Indelbed is on his own, scrawny, motherless but more or less happy.

Then one day, everything goes topsy-turvy when Indelbed’s cousin Rais discovers he doesn’t go to school and points out that the family should be doing something about this. This mundane point is a string that once tugged unravels the elaborate façade that Kaikobad had woven around Indelbed. It turns out that along with being an alcoholic, Kaikobad is a magician, an emissary to the djinn world where he’s highly-respected, and his wife (and Indelbed’s mother) was a djinn. This makes Indelbed a rare and controversial hybrid whom many djinn, including a ferociously powerful one named Matteras wants dead.

So far, so groovy. Unfortunately, Kaikobad slips into a mysterious coma and it turns out that certain members of the Khan Rahman family are ready to sacrifice Indelbed to the djinns in exchange for their own benefit.

There are three trails of story that run parallel for most of Djinn City. On the recognisable, earthly plane of humans is the story of the Khan Rahmans, particularly Rais and his amazing mother Juny. They make inroads into djinn society and uncover sinister plots, one of which includes wiping out a massive chunk of humanity. The comatose Kaikobad’s spirit separates from his body and suspended in another plane, he finds himself watching a re-enactment of an ancient war that the djinns had fought and have mostly forgotten. Finally, there’s Indelbed’s story, which takes place separate from these two.

Fantastical as these worlds might be, the concerns that they have are familiar and this novel is an excellent example of how contemporary concerns can inform a story without overwhelming it. Using djinns and humans, Hossein writes about racial and cultural purity, the effect of violence upon an impressionable mind, blackmail in the age of hackable smartphones, and a host of other serious issues. They’re all neatly woven into the story so that it never feels preachy and yet prods you to think.

Hossain’s big achievement is how skilfully he manages the three storylines because each one is distinctive. They’re different in terms of the worlds, the concerns of the characters and the pace at which time moves. Most impressive is that they’re all intriguing and as a result, when you’re immersed in one only to be yanked out and stuck in the next plane, it doesn’t feel frustrating. Hossain also manages to make the worlds collide in the end, though that, in comparison to the earlier parts, is awkwardly done. My big complaint is that Hossain doesn’t develop the hostility between Juny and Matteras to a satisfying climax. The novel is full of great characters who rise majestically above the tropes on which they’re based, but Juny has my heart. She’s angular, sharp and glitters with ferocity and determination. Damn you, Saad Hossain, for not letting her spread her wings.

And because this is now the longest newsletter I’ve written — more than 2000 words! — I’m going to sign off here. Thank you for reading.

Dear Reader will be back next week. Happy new year.