Dear reader,

Last year, I did a giveaway with practically all the titles I’d been sent while on jury duty. These were contenders for the best fiction and best debut fiction from India in 2019. I held on to a few books that I thought were special. Avni Doshi’s Girl in White Cotton was not one of them. I don’t mean I hated it (because I didn’t), but neither did I love it. Now, almost a year later, Girl in White Cotton in its swish foreign avatar of Burnt Sugar, has been longlisted for this year’s Booker prize.

About the new title and cover: This sounds weird, but it’s actually very common to have different covers and titles for the same book in different countries. I’ve no idea why “Burnt Sugar” would sound better to foreign audiences than “Girl in White Cotton”, but maybe it’s just a matter of the different cultural associations that come with white cotton.

It’s interesting how the two covers send very different signals to the reader. Burnt Sugar’s pale (but solid) lilac background with the shadowed succulent leaves in close-up hints at a dark story. It’s feminine (lilac), but menacing (the spiky bits, the shadows. Also, is that aloe vera?). In contrast, Girl in White Cotton’s cover emphasises fragility and a conventional femininity, with its delicately-sketched flowers in the background and the title spelt out using pieces of shredded paper. I mention this because when well-designed, covers put the reader in a certain headspace in which the story will unfold. When there’s a disconnect between the cover and the story, the reading experience becomes jarring and the words have to work harder to win a reader over. Both these covers were well done. They just emphasise very different aspects of the novel.

Girl in White Cotton/Burnt Sugar is about a mother and a daughter, shackled to one another by antagonism. Antara, daughter of Tara, has grown up hating her mother. So it’s a bitter pill to swallow when Tara is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and Antara must be her caregiver. As Tara’s mind steadily disintegrates, Antara finds herself remembering the past and realising that, despite all her efforts, she may well be her mother’s daughter after all.

Flitting between past and present, the novel recounts Antara’s traumatic childhood, which is something of a dirty secret (especially since Antara doesn’t want her husband to find out). As an adult, Antara moulded herself to be her mother’s opposite — the un-Tara to Tara, as it were. (Though, if you think about it, the metaphor of the name Antara would have made a lot more sense if Doshi had named the mother Pallavi or Sthayi, since all of these are musical terms that have meaning and relationships to one another. The antara always returns to the sthayi in Hindustani classical and pallavi in Carnatic music. But this would involve delving into what the names actually mean, rather than the sounds of the names.)

The contrasts between Tara and Antara quickly become evident. For instance, Tara walked out of a loveless marriage to enter an ashram and become the Osho-esque leader’s lover. Later she fell in love with a vagrant artist, caring nothing for what society thought of her behaviour. In contrast, Antara roots herself in convention. Her marriage — to a man whose defining character trait is that he’s an NRI — is bland at best. She is an artist whose work is all about documentation and control, which is obviously presented as a reaction to the chaos that she experienced because of her mother’s choices. However, the past creeps up on Antara’s present and she realises that her own capacity for cruelty and madness is no less than Tara’s.

Girl in White Cotton/ Burnt Sugar starts off powerfully and is at its best when exploring how Antara uses and abuses the power she has as her mother’s caregiver. Doshi’s prose is elegant and crafted with meticulous care. There’s some truly beautiful, lyrical writing in this book, which only occasionally feels overwrought. Unfortunately, as the focus shifts from the caregiver-patient relationship to focus on Antara, the plot loses its tension and the writing often feels self-indulgent. Antara steadily devolves into a bundle of neuroses and despite being at the centre of the novel (both as subject and storyteller), she struggles to feel either credible or relatable. It doesn’t help that the novel’s secondary characters make no impression.

While reading Girl in White Cotton/ Burnt Sugar, I kept remembering Martin McDonagh’s play, The Beauty Queen of Leenane, which is also about an entirely-unlikable mother-daughter duo. I read this play before I saw it, and it actually made more of an impression than the excellent staging I saw later. McDonagh’s plays are wordy in the best possible way. If I was ever planning a writing course, I would have aspiring novelists study McDonagh’s plays. The way he constructs characters out of just dialogue is masterful.

You can find the plot of The Beauty Queen of Leenane with a little bit of Googling, but I would highly recommend reading the play rather than its summary to properly appreciate just how vile yet tragic these women are. Maureen is a middle-aged spinster who lives with her ailing mother, Mag. They’re both horrible, with mother and daughter constantly punishing each other. Despite Mag being an invalid, she’s malicious. Maureen, for all her bitter impatience with Mag, is worn out by the life she can’t escape. You spend the duration of the play see-sawing between despising the two women and feeling for them. McDonagh is able to humanise the women despite their awful behaviour, which Doshi struggles to do in her novel. McDonagh’s twisted imagination finds ways for each woman to lash out at each other, which is the tension that keeps the audience glued to the story — what will mother/ daughter do next and how will this end? In contrast, the antagonism in Doshi’s story feels monotonous and one-sided because for all the havoc she may have wreaked in the past, the present-day Tara is hardly an adversary for Antara.

In the final scene of The Beauty Queen of Leenane, Maureen is alone at home. She puts on Mag’s cardigan and sits on the rocking chair that her mother had once occupied. It’s a chilling, heartbreaking and quiet moment in which she surrenders to the fate that she’s been maniacally fighting against for the better part of the play — repeating history, and becoming her mother. The final scene of Girl in White Cotton/ Burnt Sugar wants to convey the exact same message, only it does so by amping up the element of melodrama.

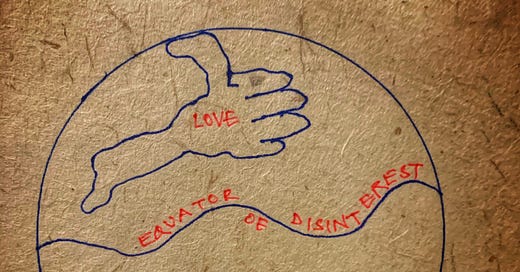

All this to say that I didn’t love Girl in White Cotton/ Burnt Sugar, but I did enjoy some parts of it. This is not me trying to be diplomatic. There’s a world of opinion that exists between the polar opposites of ‘love’ and ‘hate’. To illustrate this point, I have drawn a map.

Most things we encounter — from books to films to people — occupy territories all over this map. For me, Girl in White Cotton/ Burnt Sugar would be an island on one of the upward curves of the equatorial line.

Yes, I know. It’s true. Art’s loss is literature’s gain. But you’ve got to admit — a map of opinion is a bloody good idea. Just think of all the geography that could be added, like the Caves of Disappointment (on the continent of Hate); the Grasslands of Meh (on the continent of Love); and the Archipelago of the Forgettable (floating near the Equator of Disinterest). I’m getting goosebumps just imagining it… .

Longlists are full of uncertainties, but if there’s one book in this year’s Booker longlist that will definitely make the shortlist, it’s Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and The Light. Mantel began the trilogy with Wolf Hall in 2009 and won the Booker prize that year. The sequel (and my favourite book in the series), Bring Up the Bodies came in 2012 and also won the Booker. If The Mirror and The Light continues this trend, it’ll be the first time that every book in a series has won the Booker prize.

Mantel’s decision to write about the drama of Henry VIII’s marriages and what it meant for English politics felt almost audacious when Wolf Hall came out. Even those with only a passing familiarity with British history know about the king who married six times, beheaded two of his wives and was the father of Elizabeth I (ironic, given how obsessed Henry was with fathering a male heir). There have been films, TV shows and countless books on this period in English history, but it’s almost as though this only made Mantel more determined to fictionalise it in a way that is both imaginative and historically accurate (FYI Jonathan Rhys Meyers as Henry VIII in The Tudors was delicious, but not accurate). The English court and society that Mantel recreates in her books makes few allowances for the modern reader. She stresses upon the details that wouldn’t seem important to us today, but were of critical importance in those times, like for example the emblems embroidered on handkerchiefs.

Mantel’s exhaustive research and her command over the craft of writing make her a critical favourite and for good reason. Still, the Wolf Hall trilogy is one of those series that I recommend cautiously, because they’re not easy books to get into, especially if you’re not familiar with the history. Mantel dives deep into life in 16th century England and she’s relying on her reader being familiar with the period. For instance, she expects her readers to know the legacy of lawyer, statesman and Catholic saint Thomas More. A running theme through all three books is to cut More down to size while depicting Mantel’s chosen hero, Thomas Cromwell, as the more tolerant and honourable man. Where you do get a whiff of the 21st century is in Mantel’s decision to leaven the court intrigues with her superb women characters, who are usually written out of these histories. Mantel also makes Cromwell anti-torture, which sounds unlikely to me but then I’m not the one who has spent years studying him. Ultimately, this is very much a man’s world and Mantel doesn’t lose sight of this. Neither does she — or her reader — lose sight of how most powerful men are the sort you want to punch repeatedly.

Like in the previous books, Mantel’s fondness for Cromwell is palpable in The Mirror and the Light. She describes his every move and every thought in loving detail, which makes the novel feel almost like Cromwell’s diary even though it is a work of fiction. In The Mirror and the Light, Cromwell is at the height of his power and there he remains for the bulk of the book. It’s been a rapid ascent for the boy from Putney who had nothing but poverty and bruises in his childhood. There’s a lot of reminiscing in this final part, which helps to make this conclusion feel like a standalone. It also shows how much Cromwell has mellowed since we first met him in Wolf Hall.

For those, like me, who had to study this period in history — spoiler: it doesn’t end well for our man — there’s no surprise in terms of what will happen. As Mantel delves deep into Cromwell’s life, detailing everything from the meals he eats to the dreams he has, the tension of the novel stays taut enough to pluck like a perfectly-tuned guitar string. You flip page after page, alert to every hint of conspiracy and betrayal. In a way, you become a bit like the Cromwell of Mantel’s imagination, who kept his eye and ears open to every bit of gossip and politicking as Henry’s most trusted and powerful aide.

If you don’t know that Henry VIII eventually ordered Cromwell’s beheading, The Mirror and the Light may feel like an elaborate and slightly-aimless wander through aristocratic life in 16th century England. When the blow finally comes, it blindsided me just as it did Cromwell even though I knew it was coming, just as he presumably had. The only minor problem is that until the blow comes, there’s very little by way of conflict in the novel. More importantly, no one seems to be a match for Cromwell because he has Henry’s trust. This, of course, is the most nerve-wracking part of Cromwell’s success. Even if you’re not familiar with the precise history, it’s common knowledge that the most dangerous thing in a royal court is the king’s whimsy.

No one should pick up Mantel for plot, even though her novels are set in dramatic times. This one, for example, includes one civil war-like situation, two deaths, a remarriage, an ailing king, scheming foreign ambassadors, and one tantrummy princess — and yet, not for one fragment of a sentence does The Mirror and the Light feel plot-driven. The high drama is elegantly camouflaged in details of everyday life. Together they give you a sense of the pace at which life was lived, along with the fears, uncertainties and comforts.

The reason to read The Mirror and the Light is Mantel’s exquisite prose, which is like a portal into another time. Through the pauses in her elaborate paragraphs and the filigree of her descriptions, Mantel takes you to another time. It’s not fantastical or even the most beautiful, but it’s a world unlike the one around you (though even here, there is a plague that strikes fear in every heart). Much of this last book is set in palaces and palatial homes because this is Cromwell’s world now. There are also ghosts — of Anne Boleyn, Thomas More and Cardinal Wolsey — who flit through the book, occasionally giving it a Gothic feel.

I would highly recommend reading The Mirror and the Light out loud, even if it makes you seem a bit like a lunatic talking to themselves. Mantel’s sentences are a joy to hear because they’re so well structured, balancing the fragments so that sentences don’t feel unwieldy even though they are almost the size of a paragraph. She uses punctuation like percussion, each comma perfectly positioned to maintain a rhythm while holding the different parts of a sentence together.

As the last part in a series, The Mirror and the Light is satisfying for a history nerd and elegantly crafted as a novel, but I do think this book — like the rest of the trilogy — is a bit of an acquired taste.

Before I sign off, here’s something that has nothing to do with the Booker prize: an interview with cultural ecologist and philosopher David Abram (who was a magician before he became an ecologist). Emergence has been one of the shiniest silver linings of the lockdown for me and their podcast archive is an absolute treasure. Abram speaks about animism and throws up so many interesting ideas, and I particularly love the parts where he talks about the alphabet as a form of magic. Here’s a snippet:

“For our Indigenous ancestors, one could be wandering through the terrain and have one’s attention snagged by a boulder with patches of crinkly black and red lichen spreading on their surface, and you would focus your eyes on a patch of lichen and abruptly hear the rock speaking to you. Well, that’s not so different from us waking up in the morning, walking to the kitchen, opening up the paper, and focusing our eyes on a few bits of ink on the page, and suddenly we hear voices and we see visions of events happening in the White House or in Iraq. We focus our eyes on these ostensibly inanimate bits of ink on the page and we hear voices, conversations unfolding between people on the far side of the world. This is animism, folks. It’s an intensely concentrated form of animism, but it’s animism, nonetheless; as outrageous as a talking stone.”

For a lot of us, July has been difficult, harder and stranger to bear than the previous months. Perhaps we’ll say this of August too. Whatever the month may bring, here's to the magic that is all around us and the spells that literature can cast.

Take care, stay safe and thank you for reading. Dear Reader will be back soon.

I found White Cotton repugnant. That's because I dont anyone who'd steal her mom's lover just as the mother steals the husband