Dear Reader,

There is something weird about not being able to find the right words to write about a book that is all about forgetfulness, but that’s where I am with The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa. (Is this going to stop me from writing many, many words on the book? Apparently not.)

Originally published in Japanese in 1994, The Memory Police was translated into English last year. It's an excellent translation by Stephen Snyder, which is worth highlighting not only because translators don’t get enough love but because so much of The Memory Police relies upon a shared sense of normalcy between the reader and the text. From the architecture of homes to codes of behaviour, Japan is not likely to be confused with other places (every culture is distinctive, but Japan's got a reputation for being sharply unlike other societies and protective of its differences). Yet The Memory Police feels like it belongs everywhere and nowhere simultaneously.

The novel is set on an island. What is distinctive about this island is that things disappear from it. It's never made clear on whose orders an object or idea disappears. All we know is that things disappear without warning. It could be calendars — the disappearance of which fixes time in the island and stops the cycle of seasons, trapping residents in unending winter — or ribbons or photographs or books. Suddenly the word for the object has no meaning and residents are required to purge those things out of their lives. Ensuring no one holds on to the disappeared are the Memory Police whose responsibilities include people disappear. People whose memories refuse to adapt to the new, emptier reality are targeted by the Memory Police.

Our narrator is a woman novelist whose mother was among those who didn't forget and was taken away by the Memory Police. When the novelist learns that her editor — a married man who is expecting a child — is one of those whose memory isn't malleable, she decides to save him by constructing a secret room in her home where she hides her editor from the Memory Police. While the novelist and her editor try to withstand the disappearances and the outsmart the Memory Police, the novelist writes a story about a typist who is held hostage by her lover.

Almost nothing in The Memory Police is given a name and the storytelling has a timeless quality to it. Even before the disappearance of calendars, it's difficult to calculate how long has passed between incidents. The characterisation is thin and as a result no one feels entirely whole. This didn’t feel like a flaw, but rather, reflective of how everyone on the this island is flattened down as pieces of their lives and selves are stripped away from them.

Most descriptions of The Memory Police contain the word "Orwellian" (dystopic setting; authoritarian forces etc), but rather than a variation of the doublespeak of Orwell's 1984, what Ogawa presents is erasure. I have no idea how urgent a concern it was in Japan in the 1990s, but it's timely and relevant in the present when all over the world, majoritarian narratives are drowning out others. The marginalised have always struggled to have their realities acknowledged by those in the centre, but it's a burning concern in our present when so many stories are being overwritten, beginning with the demolition of historical monuments to entire populations being wiped out or 're-educated'. In India, indigenous histories from the North-east, contemporary records in Kashmir, Dalit narratives from across the country, rewriting history to refashion Muslim figures are just a few examples of narratives in danger of disappearance. Most of us do what the people in The Memory Police do — we go on on as though nothing has changed.

But that's not all The Memory Police explores. The book is as much about grappling with loss and soldiering on despite the world losing its richness and allure. Also layered within the two plots is an unsettling look at abuse and dysfunctional 'love'. As the novelist writes the story of the typist, you start noticing parallels between reality and fiction: secret rooms; hideaways who are forced into silence; the ways in which a captor exercises their authority over a captive; the gatekeeper's power, and how impossible it is to break free when you've succumbed to the idea that you are powerless.

I have a feeling The Memory Police is a bit like a Rorschach painting. Read it to find out what you'll see in it. Just make sure you have a really good book to follow it up with because to read even a mediocre book after The Memory Police feels unbearably dissatisfying. I’ve put up some quotes from the book here.

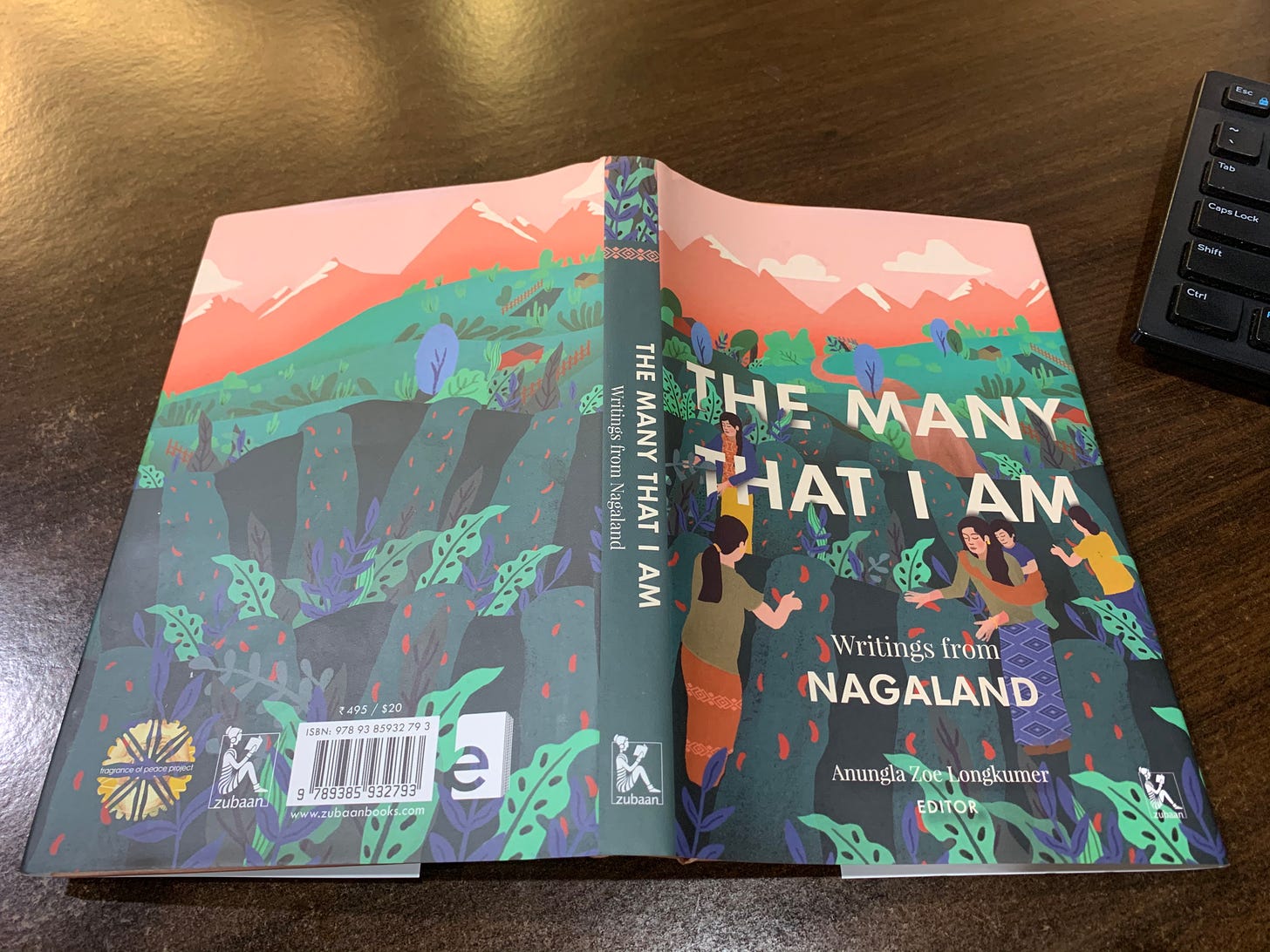

I'd waddled up to The Many That I Am: Writing from Nagaland because a) the cover is gorgeous, b) I thought that after a book on disappearance, stories from a culture that has transitioned from oral to written would be...comforting. Edited by Anungla Zoe Longkumer, The Many That I Am has a solid introduction to contemporary Naga writing. The book also has some works by Naga artists, which aren’t served well by the black-and-white reproductions. The stories in the volume are a mixed bag, ranging from properly dreary to memorable. Some of the stories read awkwardly in English, as though they are stilted translations. Wade through them, and you reach the good ones.

My favourite from the volume is "Storyteller" by Emisenla Jamir. It's more than a little creepy — even now, I just have to close my eyes to imagine a glowing red line separating the head from the face, and I get goosebumps — and weaves in themes like the importance of pottery, lineage, continuity and adapting to a changing world.

Not as memorable as Jamir's "Storyteller" but still good were "The Letter" by Temsula Ao, "Cherry Blossoms in April" by Easterine Kire and "My Mother's Daughter" by Neikehienuo Mephuo. It’s just that in a volume as slim as The Many That I Am, I'd argue every page should be compelling and that is not the case.

But this also raises a different question — who are these stories written for? Is it meant to be an introduction for mainlanders like me or is it a little mirror for Naga readers? This is the kind of question I don't ask of, for example, Ogawa. When I read The Memory Police, I don't wonder whether she and her fiction represent Japan as a whole. The reason for this is that there is a lot of translated Japanese fiction (and non-fiction) available to a reader. As a result, all the responsibility of representation doesn't fall on one book or one writer.

Unfortunately, we're far from that point in Indian publishing, so books like The Many That I Am are expected to represent entire cultures and communities. The Many That I Am is very aware of this and while the introduction is ready to shoulder that unfair burden, the stories are less able. So no, it’s hardly a must-read, but I'm very grateful it’s around and for the writers from the North-east that Zubaan publishes. Also, I’m totally going to be looking out for Emisenla Jamir’s prose writing. You can see some of her poetry on Instagram, but I liked her short story better. Unfortunately, none of her prose appears to be online. Insert grumpy face here.

And finally, a book that has spoilt me because ever since I finished it, I’m hungry for something as insightful and right now, I’m yet to find it. Consequently, thanks to Ursula Franklin's The Real World of Technology, my pile of partially-read books is a small tower. Franklin’s book is stupidly expensive so I would completely understand if you start looking for pirated versions. (They are, like the truth, out there.)

I came across Franklin's name while reading Chayanika Shah's essay prefacing the Indian edition of Sara Ahmed's Living A Feminist Life. Shah quotes a few lines written by Franklin that made my ears perk up more pointily than they have in years.

"Social change will not come to us like an avalanche down the mountain. It will come through seeds growing in well prepared soil – and it is we, like the earthworms, who prepare the soil. We also seed thoughts and knowledge and concern. We realize there are no guarantees as to what will come up. Yet we do know that without the seeds and prepared soil nothing will grow at all… we need more earthworming."

In a flash, I’d abandoned Ahmed's book and scuba dived into Google, looking for information on Franklin. Born in Munich, a Holocaust survivor (Franklin was in a work camp for 18 months), a pioneer in a field that combines archaeology and metallurgy, humanist, pacifist, feminist and giver of incredible lectures, the only word I have for Franklin is magnificent. There's a good interview with her here, which has introduced to my vocab the glorious term of "lady patriarchs" ("It makes no difference in many ways if it’s a woman or a man. In particular positions, a woman can be as inconsiderate a lady patriarch as a male patriarch would have been. So the issue is the hierarchical structuring; the issue is patriarchy." You tell ‘em, Ms. Franklin!)

Anyway, so that previous quote about "earthworming" is from The Real World of Technology. It's ridiculous how a set of lectures from 1989 doesn't feel even slightly dated in 2020. Franklin's analysis of the past and her examination of how technology impacts society is so intensely relevant today that you will find yourself thinking these lectures must be on YouTube. (They're not, but I did find the first one on CBC.)

In The Real World of Technology, Franklin puts forward her theory that technology has been developed with the intent of making members of society compliant and less capable of independent decision-making. She examines power, social institutions, practices and hierarchies, to show how technology cements structures. Technology is a system for Franklin. It's a mindset; an agent of power and control.

The ideas that Franklin seeds through her lectures are profoundly interesting and it’s beyond me to discuss them here (especially since this newsletter is already gigantic), so I’m just going quote a couple of chunks from The Real World of Technology to let you glimpse Franklin’s awesomeness.

"Standard histories of technology rarely acknowledge the contributions of women to the development and spread of modern technologies. Yet it is entirely fair to say that without the work of women, their willingness to do extremely delicate but repetitive jobs, and their ability to learn intricate work patterns, the electrical and electronic technologies could not have developed the way they did. ... Who but women would take up those monstrous early typewriters and learn to type faster than people speak?"

“…prescriptive technologies have brought into the real world of technology a wealth of important products that have raised living standards and increased well-being. At the same time they have created a culture of compliance. The acculturation to compliance and conformity has, in turn, accelerated the use of prescriptive technologies in administration, government and social services.”

“I would venture that the social and political needs for an enemy are so deeply entrenched in the real world of technology (as we know it today) that new enemies will quickly appear, to assure that the infrastructures are maintained. I am personally very much afraid that there will be a turning inward of the war machine. After all, the enemy does not have to be the government or citizenry of a foreign state. There is lots of scope — as well as historical precedent — for seeking the enemy within.”

“It seems such an egocentric and technocentric approach to consider everything in the world with reference to ourselves. Environment essentially means what is around us, with the emphasis on us. It’s our environment, not the environment or habitat of fish, bird or tree. … Everything possible is done to equalize the ambience — to construct an environment that is warm in the winter, cool in the summer — equilibrating temperature and humidity to create an environment that does not reflect nature. Nature is then the outside for “us” who are in an internal cocoon. Indeed, technology does allow us to design nature out of much of our lives. … Sometimes I think if I were granted one wish, it would be that the Canadian government would treat nature the way Canadian governments have always treated the United States of America — with utmost respect and as a great power. … Obviously, nature does not take kindly to what is going on in the real world of technology. Nature is retaliating, and we’d better understand why and how this is happening. I would therefore suggest to you that, in all processes of planning, nature should be considered as a strong and independent power. Ask, ‘What will nature do?’ before asking ‘What will the Americans do?’”

Franklin wrote this in 1989. How’s that for brilliant?

I can’t recommend The Real World of Technology enough. The examples Franklin gives are mostly rooted in Canada and the global north, but the ideas that she’s discussing are far more profound than geography and political boundaries.

So those are the highlights of my reading in January 2020. My quest for properly satisfying pop romances continues with little success (to be fair, it’s hard for any romance writer to give Ursula Franklin a run for her money, but the job of a reader is to be demanding). In the meanwhile, there’s this one set in Mumbai, with a journalist, a confused person and two good men. I had fun with it.

I’ve also been trying to blog more and there are posts on the #OccupyGateway protest in Mumbai, Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story that I managed to write in the middle of all the other swirling nonsense that is real life.

We’ve got a new episode of The Lit Pickers up, but I’ll send out a separate newsletter with relevant links because this one is already the size of a small continent.

Thanks for reading and Dear Reader will be back soon.