Dear Reader,

I am, as usual, late with this newsletter, but I come bearing gifts.

Before that though, just one thing. You know how I give you links to the books I’m talking about? They’re almost always to Amazon, but that’s genuinely only for convenience. Never forget: Amazon is the evil corporation that treats workers horrifically and has decimated bookstores as well as the publishing industry internationally. If there is a bookstore in your neighbourhood/ city that you can patronise, please do that. You know how the Japanese came up with “forest bathing”? Bookstores let you do book bathing — i.e. cocoon yourself with books — and it’s a winsome feeling. I would still like to believe there is a world in which Amazon and the local bookstore can both exist, but that’s only possible if readers splurge at the local bookstore and spend frugally on Amazon. So please, go to the bookstore, walk around the shelves and buy some books.

With that out of the way, let’s get to the free stuff.

As I’d mentioned in the previous newsletter, I was on the jury that chose two prize winners in the fiction categories for Tata Literature Live! Raj Kamal Jha’s The City and the Sea, a surreal and heartbreakingly-sad novel about the times in which we live, and The Far Field by Madhuri Vijay won top honours. Vijay masterfully tackles a range of complex ideas including India’s relationship with Kashmir, unhappy marriages, and a daughter’s fraught relationship with her mother in The Far Field. Highly recommended.

This whole jury business has landed me with multiple copies of many books and a visceral awareness that I don’t ever want to see some of these titles ever again. Hence Dear Reader’s first giveaway.

Before you start picking titles, you should know a few things:

One person can pick only one book.

You have a week to write back with your pick.

Your mailing address must be in India.

You have to be a subscriber of Dear Reader.

Don’t be impatient. This is me and India Post at work, not Amazon.

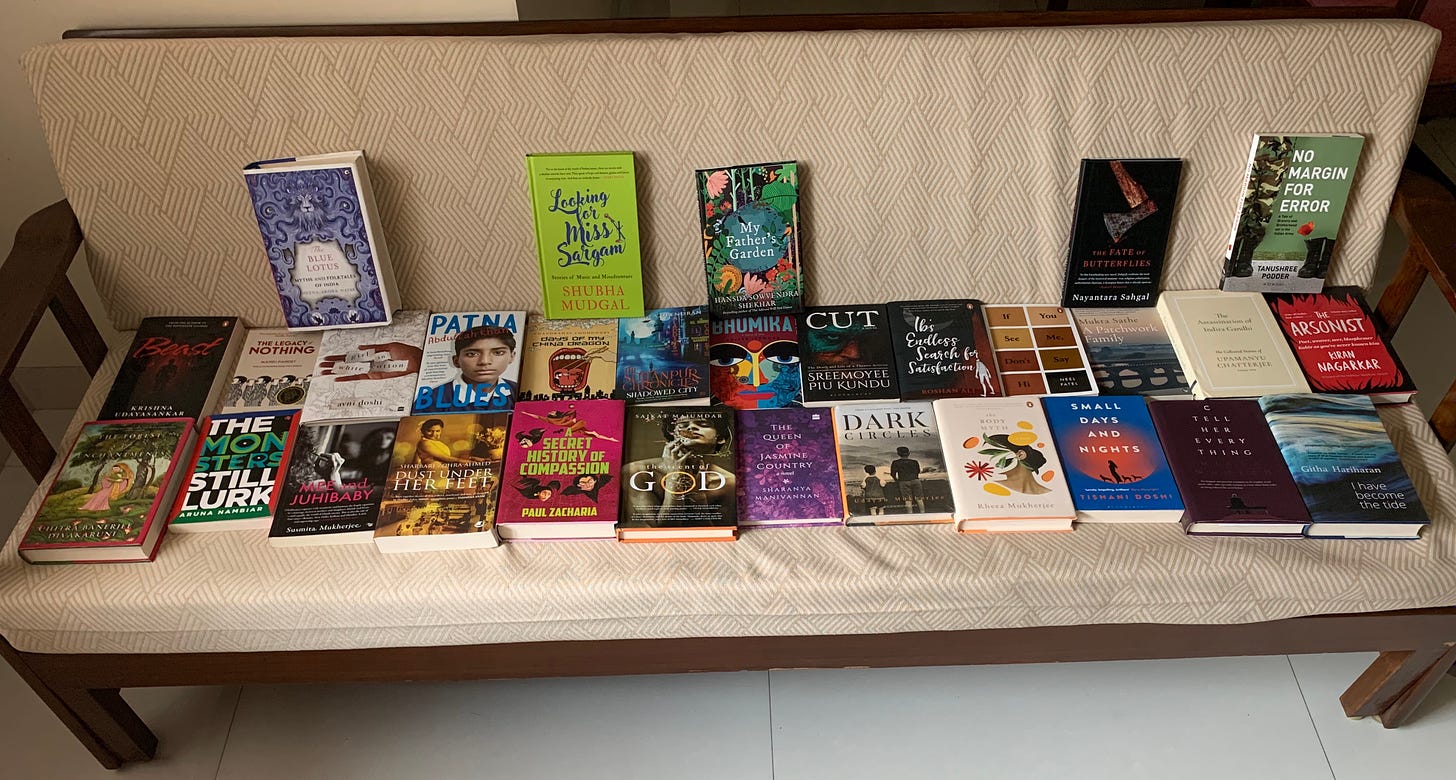

So here it is, a couch full of books to give away:

In order of appearance:

Beast

The Forest of Enchantments

The Legacy of Nothing

The Monsters Still Lurk

The Blue Lotus

The Girl In White Cotton

Mee and Juhibaby

Patna Blues

Dust Under Her Feet

Looking for Miss Sargam

Days of My China Dragon

A Secret History of Compassion

The Sultanpur Chronicles

The Scent of God

My Father’s Garden

Bhumika

The Queen of Jasmine Country

Cut

Dark Circles

Ib’s Endless Search for Satisfaction

The Body Myth

If You See Me Don’t Say Hi

Small Days and Nights

The Fate of Butterflies

A Patchwork Family

Tell Her Everything

The Assassination of Indira Gandhi (and other stories)

I Have Become The Tide

The Arsonist

No Margin for Error.

Take your pick and let me know by replying to this newsletter.

Until I signed up to be on this jury, I genuinely thought I had a fair idea of what comes out in Indian publishing. I was wrong. I knew about only the books by authors whom I know personally and those who range from established to famous. It’s tempting to put all the blame on how little space books (and culture in general) gets in the media, but that’s not the whole story. The publicity machine doesn’t crank up as it should for new writers. The distribution network doesn’t work as well because no one’s pushing for them if they’re not already known for some reason. When you look at the numbers, whether of sales or clicks, there seem to be more writers than readers. We seem to belong more to a cult of celebrity than a community of readers.

Which seems like an excellent moment to thank all of you for subscribing to and reading a newsletter about books and reading.

There a bunch of books I’ve read since the last time I wrote, but I’ll tell you about them in a separate newsletter so that I don’t confuse the giveaway responses with regular responses.

Before I go though, here are a few links.

“The metaphor, heavily used in the 19th century as a means toward the ecstatic sublime, became more passé after the World Wars, when the pastoral dream was no longer feasible amidst European fields rotting with cattle corpses. I wanted to use the metaphor differently, on terms removed from a Eurocentric worldview.

Vietnamese refugees, for example, use metaphor as a coping mechanism; metaphor provides a way to talk about trauma without stating the experience outright. An abortion is described as having “papaya seeds scraped out of you,” or sexual assault as having “the doorway of your body broken into.” To die is to”“get on the road.” Likewise, when Abel Meeropol wrote the poem “Strange Fruit” about the lynching of African Americans in the South, he was not reaching for the Romantic sublime—but to render the horrific via an alternative speech act. The metaphor in the mouths of survivors became a way to innovate around pain.”

“Indeed, she opens by explaining that literary criticism is always performed through the lens of its moment, urging her readers to “discover in the lines of association I am making with a medieval sensibility and a modern one a fertile ground on which we can appraise our contemporary world.” Morrison’s Beowulf interpretation highlights what other critics, following Tolkien’s lead, have deemed marginal. She decenters the white male hero, focusing instead on the racialized, politicized, and gendered figures of Grendel and his mother, who in Tolkien’s read would have been black. In his article “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” his white male gaze concentrates on what these two “monsters” can do for Beowulf’s development as the white male hero of Germanic epic. Morrison, on the other hand, is interested in Grendel and his mother as raced and marginal figures with interiority, psyche, context, and emotion.”

“I submit that, while I might want being Indian to be a superpower, a special ability, actually, contrary to popular myth, being Indian doesn’t even get you free college, right? It doesn’t jack you into casino money, it doesn’t make you automatically in tune with nature, and it doesn’t make you any sadder than everyone else about unrecycled cans in the creek. It also doesn’t make your cheekbones or your nose like this or like that, your name exotic to American ears, your hair long or short, your religion here, there, or anywhere.

It just means you’re Indian, in a world that’s largely not Indian. It means you probably don’t see yourself in the main role on the television show. It means you’re reduced to being the most insulting mascot as often as not.”

And finally, this year’s Bad Sex Award, which are truly, amazingly bad. Honestly, these literary fiction types really need to read some paperback romances because boss, those writers never come up with nonsense like “he would then rub his organ as if he were furtively making omelette rolls.” Shudder.

Right, so that’s it from me for now. Dear Reader will be back in a couple of days to tell you about Trick Mirror, Fear of Lions and a few more books I’ve read since I sent out the last newsletter.

Thanks for reading.